The Gordons were a Modern Orthodox family. My parents and I weren’t sure what that meant, except that they “kept the Sabbath” (Where? How?) and knew way more about Judaism than we did. They had two daughters — Tamar, who, like, me was 4 years old, and Ilana, who was a year older. We all got along well, so they invited us over for our first Passover. We arrived at the Gordons’ home freshly scrubbed, excited and hungry.

How was this night different from all other nights? Although we showed up at a normal dinner hour, we didn’t eat until almost midnight. If it was hard for grown-ups to sit through such a lengthy ritual, it was excruciating for a trio of hungry kids. We went feral. We climbed the walls, raced around the house, rolled on the floor, whined, cried and staged a mini-theatrical production under the table. I think my parents were shocked not only by the length of the seder but also by the commitment required to be a Jew. Our first religious celebration in the New World was a bust.

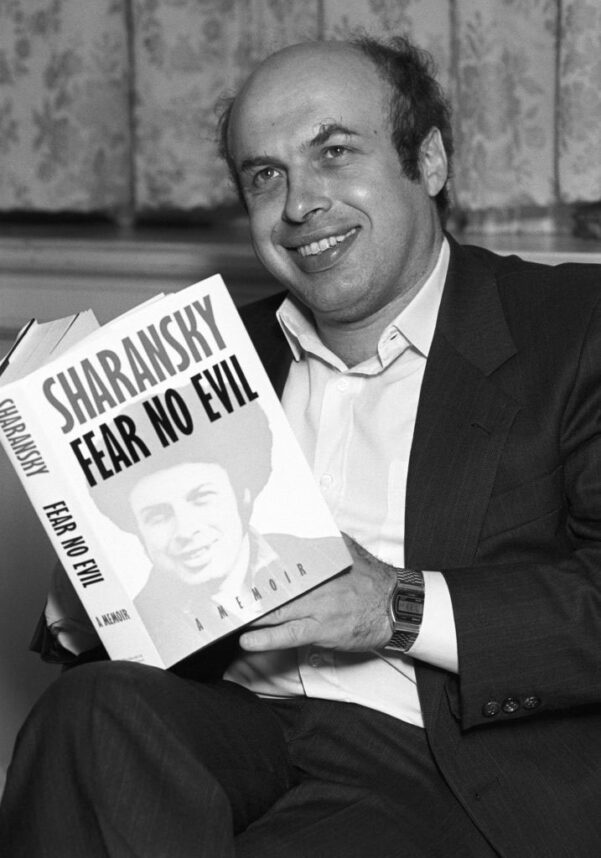

I am an immigrant, technically a refugee, but now so Californian you’d never know it. (I had to train myself to stop saying “hella good.”) My parents had wanted to leave the USSR before I was born. That’s why it took so long for them to choose my name. They needed something that wouldn’t be out of place once we were abroad, but wasn’t so foreign it would elicit the ire of Soviet apparatchiks. I was almost a Ludmilla, I am told, but I dodged that bullet. They settled on Elina, a Greek derivative of Helen. Instead of launching a thousand ships, there was a single train. In 1978, 10 days after my third birthday, my father held me out of the window of the train that would carry us to Vienna. Standing on the platform, my grandparents looked at me for what they assumed would be the last time. In the case of both grandfathers, it was.

We were born Jewish, but what does that mean when you’re not allowed to be Jewish, to celebrate religious holidays or express your identity in any meaningful way? When we came to the United States, it must have been tricky for my mom, who was trying to instill traditions she hadn’t grown up with or practiced. We started attending synagogue, not fervently, but enough. We were going as much for the sense of community as we were to commune with Adonai.

A few years after that disastrous seder, I was visiting my father (my parents had divorced by then), and as I was grudgingly helping him mow the lawn, he asked, “Do you know why Moses and the Israelites had to spend 40 years wandering in the desert?” I was caught off guard. It was beyond strange for my profoundly irreligious father to suddenly quiz me about Old Testament parables. I was stumped. “It’s because God wanted the older generation to die,” he explained. “He knew that even though they had been freed, in their minds they would always be slaves. God wanted the people who entered the Promised Land to be free. Your mother and I wanted to make sure that you would never be like us, that you would never be a slave. That’s why we came to America.”

I’d been taught the Exodus story in Sunday school, but until that moment, I hadn’t understood it. The way he had emphasized slavery — as though we’d escaped a literal, physical bondage, not merely a metaphorical one — made me suspect we were profoundly different from American-born families. It wasn’t just the accents, or the clothes or the sandwiches made with butter instead of mayo. It was the legacy my parents carried with them and imparted to me. There’s an aphorism that says youth is wasted on the young, but I often think that freedom is wasted on the free. For all their differences, my mother and father both possessed an intense appreciation for freedom, the kind that can only come from having lived without it.

I think about all the reasons my parents left their homeland and their family when the price of doing so was almost unbearably steep. I think about this most often at Passover. They came seeking economic opportunities, but they also wanted to live in a world where they weren’t being continually watched or asked to spy on their neighbors or expected to prove their patriotism by adhering to the state-sanctioned ideology.

Much has changed since 9/11. The Patriot Act enacted by Congress persuaded all of us — Americans — to happily sacrifice our liberties; reports of prisoners being tortured, abused and held in legal limbo didn’t spark our collective outrage, and reports of leaked documents underscored how thoroughly we’re all being monitored by our own government. The most sinister trick is making us all complicit in these policies, then convincing us that opposing them is un-American. To people like my parents, all this must look distressingly familiar. When my father grafted the biblical narrative of exile and redemption, which Jews recount at every seder, onto our own story, he drove home for me that human bondage begins somewhere much quieter than in a public square. It begins in our own minds.

Elina Shatkin is a journalist, filmmaker and radio producer living in Los Angeles.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.