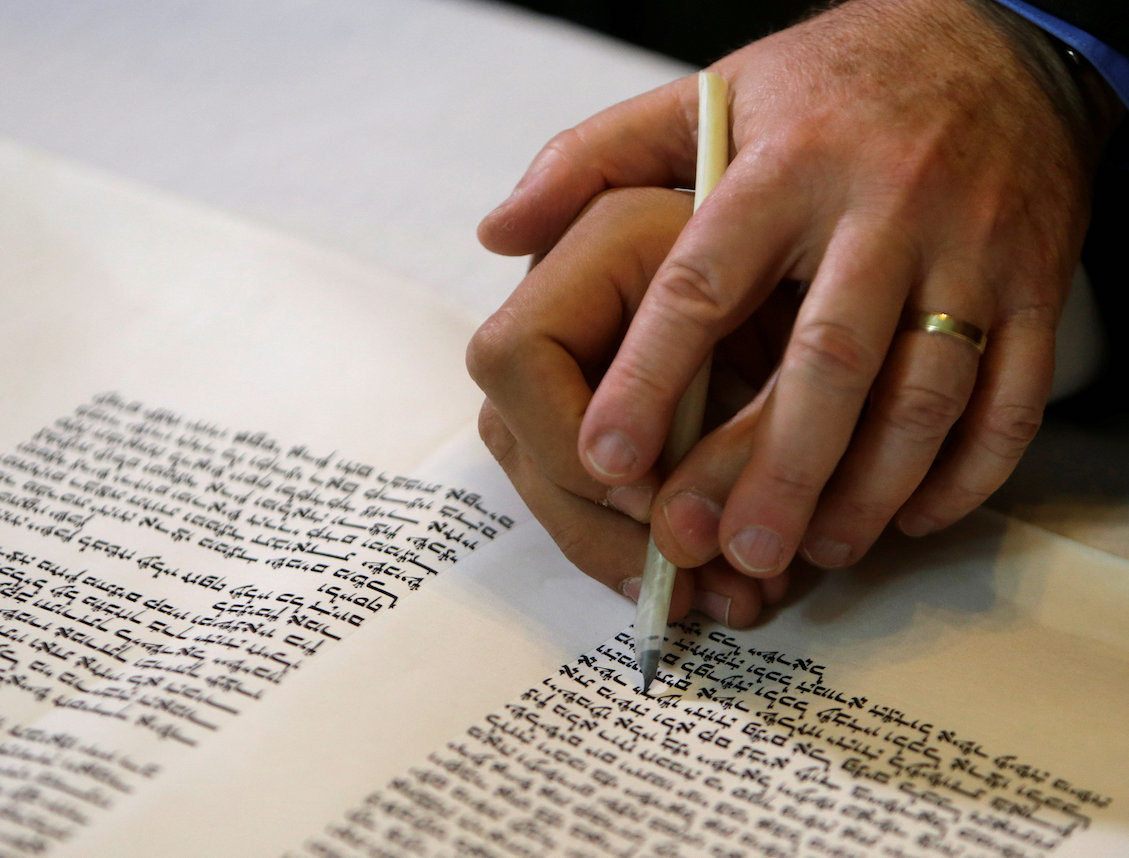

Reuters/David W Cerny

Reuters/David W Cerny Just before the summer, students in my school’s senior class returned from a trip to Poland, a haunting journey into the Jewish ashes of Eastern Europe — the horrid death camps of Majdanek and Chelmno, the site of a genocidal rage to which for decades the world has sworn “Never again!”

And yet last month, white supremacists and neo-Nazis with menacing swastika flags on full display paraded through the streets of Charlotsville, Va. Even though we knew in the back of our minds that this age-old brand of Jew-hatred persisted, to actually see it — to witness that sort of hate and aggression — brought our worst fears and anxieties into terrifying focus.

So now what? How are we supposed to react to such hate and hostility?

There’s a strong impulse to meet fire with fire and hate with hate — a method understandably advocated by some on the left. However, our tradition, which has long had to respond to the scourge of anti-Semitism, has charted a different path, one captured in this week’s parsha.

Consider the following verse: “You should not hate the Edomite, for he is your brother; you should not hate the Egyptian, because you were a stranger in his land” (Deuteronomy 23:8). The Rambam in Moreh Nevuchim expands (Part 3, Chapter 42):

The Law correctly says, “Thou shalt open thine hand wide unto thy brother, unto thy poor” (Deuteronomy 15:11) … The Law has taught us how far we have to extend this principle of favoring those who are near to us, and of treating kindly everyone with whom we have some relationship, even if he offended or wronged us; even if he is very bad, we must have some consideration for him. Thus the Law says: “Thou shalt not abhor an Edomite, for he is thy brother.” Again, if we find a person in trouble, whose assistance we have once enjoyed, or of whom we have received some benefit, even if that person has subsequently done evil to us, we must bear in mind his previous [good] conduct. Thus the Law tells us: “Thou shalt not abhor an Egyptian, because thou wast a stranger in his land,” although the Egyptians have subsequently oppressed us very much, as is well-known.

To be clear, this is not to say that certain groups of people aren’t, in the Torah’s estimation, beyond the proverbial pale. In fact, the last item in this week’s parsha is a discussion of Amalek and an exhortation to “obliterate the remembrance of Amalek from beneath the heavens” (Deuteronomy 25:19). The Torah is quite unambiguous about that.

But Amalek, it seems, occupies a singular category. According to the Rambam, even the Egyptians, who brutally enslaved and oppressed us for hundreds of years, do not deserve our unmitigated hate. We are — somehow — to afford them empathy and even appreciation. The kabbalistic work of Tomer Devorah echoes this sentiment, instructing that a person should go to great lengths to “have love in his heart” not just for his friends but especially for even his most wicked of enemies.

Why? Why must we do that? Is the Torah instructing us to be naive pushovers? Is it in the spirit of kumbaya?

I do not think so. Turning the other cheek isn’t a Jewish value. Rather, I think the Torah understands that while meeting hate with hate and aggression with aggression certainly feels tremendously satisfying, it’s often not the most effective path toward creating a new and better reality. Hate is not constructive — it is, by its nature, a destructive force. It closes possibilities. It fortifies silos.

So when we look at our enemy in 2017, which is it: Amalek or Egypt? Well, if anyone on the planet belongs in the category of “Amalek,” Nazis (and neo-Nazis) would most assuredly fit that bill. We have to speak up loudly and with force in denouncing them and their message of hate — that’s more than a moral imperative, it’s an existential matter for Jews. (Responding with physical violence, on the other hand, is something else; we are fortunate in this country to have law enforcement and a legal system that governs issues of free speech that we must respect.)

But I believe the Torah teaches us that we also have a responsibility — one that might seem counterintuitive and certainly difficult to fulfill — to find ways to inject love into an environment of hate, and empathy into a whirlpool of ignorance. We cannot watch as spectators as this aggression and hate and hostility continue to snowball even further.

Most individuals on the “far-right,” as it were, are not neo-Nazis. They are complicated human beings with hopes and fears and anxieties. I don’t think we can or should devolve into vitriolic shouting matches with those individuals. We need to open dialogue. We need to find common ground.

Even as we stand our ground and protect ourselves, our families and our communities, we must, through it all, seek to find those who would be willing to have conversations, and have them. To build bridges, and not to burn them.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.