Dr_Microbe/Getty Images

Dr_Microbe/Getty Images When people in the Jewish community think of genetic diseases, they usually think of Tay-Sachs disease. The most common form is infantile Tay-Sachs, in which symptoms start at around three to six months of age. The baby can become overly startled by noises and movement, lose the ability to sit, turn over or crawl, have difficulty swallowing and lose vision or hearing. The condition is usually fatal by the age of three to five.

Tay-Sachs is passed down from parents to child. When both parents carry a mutation or change in the Tay-Sachs gene, each of their children is at 25% risk for the disease. While the gene that causes Tay-Sachs is more often found in people with an Ashkenazi Jewish background, the disease occurs in all populations across ethnic backgrounds. Therefore, non-Jewish and interfaith couples are also at risk for having affected children.

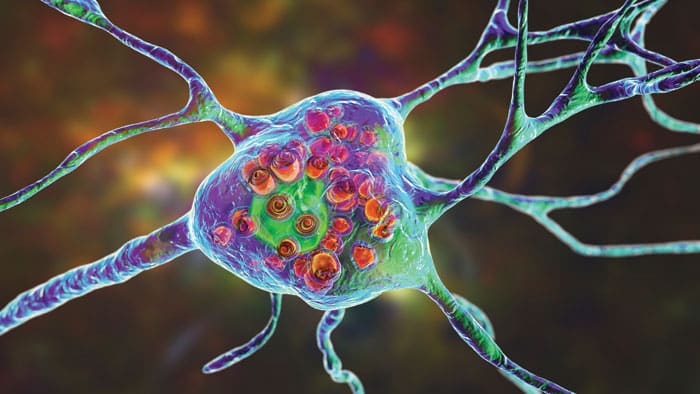

Tay-Sachs disease is caused by the absence of an enzyme (hexosaminidase A) that helps break down fatty lipids called gangliosides. The lipids subsequently build up to toxic levels in the brain and spinal cord, affecting the function of the nerve cells. After researchers linked this enzyme, or more specifically, the lack of it, to Tay-Sachs in 1969, carrier screening for the disease was able to be implemented across the Jewish community beginning in the 1970s. Potential parents now had the vital information to know if they were at risk for having an affected child. As a result, the number of babies born with Tay-Sachs has reduced significantly in the past 50 years.

But while some people think that Tay-Sachs has been eliminated, babies are still being born with this disease. How is this possible, when genetic testing is so readily available?

The fact is, many people still don’t know about the need for testing. Take Bonnie Davis’ family, for instance. Her son Adam was born with Tay-Sachs, as Bonnie and her husband were unaware that a simple genetic test could have informed them of their genetic risk. Bonnie says, “Tay-Sachs is commonly carried by Ashkenazi Jews, which we both are. Our obstetrician should have met the standard of care and provided us with the option to obtain genetic testing. He didn’t. Most rabbis will counsel Jewish couples to have genetic testing prior to marriage. Ours didn’t. Many Jewish youth learn about Tay-Sachs at religious school or on their college campus. Neither of us did. We fell through the cracks and never knew we needed genetic testing. Knowledge is power and knowing your carrier status for genetic diseases gives people the power to create a healthy family and avoid the devastation of having a child with a fatal genetic disease.”

One person who was moved to action by her child’s death from Tay-Sachs is Shari Ungerleider. Shari, who lost her son Evan 24 years ago, reflects, “Evan’s memory propels me to act, transforming tragedy into a force for good. Raising awareness about carrier screening has become my mission, sparing others the anguish we endured. Preconception carrier screening, coupled with genetic counseling, is essential for all aspiring or expanding families.” Shari is now an outreach coordinator for JScreen, a nonprofit genetic testing initative out of Emory University. Shari and her husband Jeff have gone on to have three other healthy children. She explains, “With each of my other pregnancies, I updated my carrier screening for diseases that were added to the panel. Knowing that Jeff and I were both carriers for Tay-Sachs disease, we were able to make family planning choices that enabled us to have healthy children. We chose to get pregnant naturally and have a CVS test performed at ten weeks. From the bottom of my heart, I believe that every couple should be able to make educated decisions based on accurate genetic information.”

Accurate information was something not afforded to Kevin and Lisajane Romer. Their son Mathew, born in South Florida in 1995, was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs despite both parents being tested and told that they were not carriers. “We did everything right. We both got tested beforehand and were told that neither of us was a carrier,” Kevin recalls. The couple later learned that their screening tests had been both administered, and interpreted, improperly. So, in addition to caring for their dying child, Kevin said, “We made it our immediate mission to improve testing procedures and protocols. We didn’t want any other parents to be blindsided and so we did something about it and founded The Mathew Forbes Romer Foundation.” Since its launch, the foundation has helped genetically test thousands of individuals at screening fairs. In addition, it has funded and produced, in association with Dr. Michael Kaback, the first ever laboratory training video and distributed it to 40 laboratories worldwide to help prevent errors in genetic testing.

With the mission to spread awareness about the importance of genetic carrier screening in both the Jewish and non-Jewish communities, the Jewish Journal helped launch and market GeneTestNow eleven years ago. Since then, technology has advanced considerably. Instead of blood tests that screen for just a few genetic diseases, at-home saliva tests like those offered by JScreen test for more than 200 genetic diseases, making screening more comprehensive and accessible than ever.

As much as we’d like to wish that Tay-Sachs is no longer a problem, the disease remains a deadly foe. But with carrier testing, couples can get the information they need to put the odds on their side and plan for healthy families.

For more information about genetic carrier screening, visit GeneTestNow.com. To receive $100 off an at-home screening kit from JScreen, visit GeneTestNow.com/getting-tested.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.