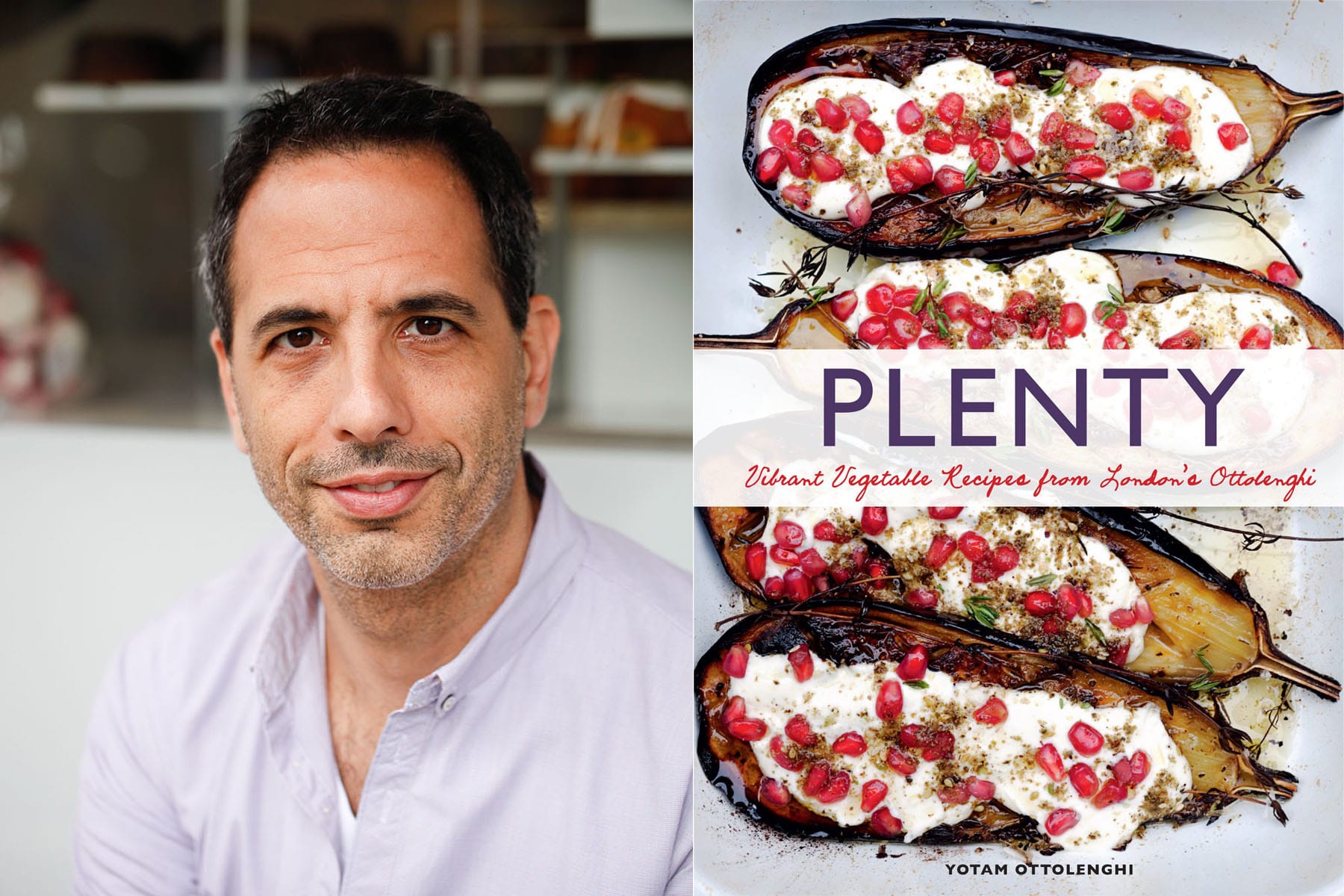

Yotam Ottolenghi (Wikimedia Commons. This work has been released into the public domain by its author, Keiko Oikawa.)

Yotam Ottolenghi (Wikimedia Commons. This work has been released into the public domain by its author, Keiko Oikawa.) About the time that knishes started disappearing and Jewish delis became scarce enough to deserve a documentary, Jewish cuisine got a makeover. In the same way that Italian food morphed from mountains of meatballs and spaghetti in the ‘50s to the svelte, more refined Tuscan cuisine of the ‘80s, Jewish food underwent a slimming down in the 2000s. Out went the sky-high corned beef sandwiches and caloric kugels (except for special occasions); in came the spicy shakshukas, colorful salads and an avalanche of exotic eggplant dishes.

Call it the Ottolenghi effect. In 2002, Yotam Ottolenghi, the Israeli-born London chef, reinterpreted Middle Eastern cuisine and made it chic, transforming forgotten vegetables like kohlrabi and fava beans into bright, sexy super stars. And though he never calls his cuisine Jewish, or even Israeli, the fragrant flavors of the Sephardic diaspora pop up everywhere—making Ashkenazic food look dowdy by comparison. Preserved lemons, pomegranates, dried figs and dates, olives, labneh, cumin, coriander and cardamom woke up taste buds tired of the same old thing—and all that schmaltz.

Sifting through the cuisines of Israel, Morocco, Tunisia and Turkey, Ottolenghi synthesized a cheeky Jewish cuisine with big acidic flavors, vibrant colors, and healthy ingredients. For the last twenty years, he has been serving it up in gorgeous cookbooks and bountiful displays at his London delis and restaurants, always accompanied by eye-popping pastries.

Ottolenghi came to my attention in 2010 when my son started cooking from the vegetable cookbook “Plenty.” When he served a roasted cauliflower salad with pine nuts and labneh dressing for lunch, I was sold. Since then, I’ve collected several of the books, “Jerusalem” being my favorite. His beautiful cookbooks are the place I turn when I need one brilliant dish to bring to a potluck. Or when I just want a visual feast.

As much as the long ingredient lists drive me crazy and his multi-part recipes scream, “Turn the page,” the former cookbook writer in me must admire his global influence. Ottolenghi’s series of eight best-selling cookbooks is now seminal to culinary culture. Like Julia Child’s “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” in the ‘60s and “The Silver Palate” in the ‘80s, Ottolenghi has changed the way a generation cooks and thinks about eating—placing vegetables, pulses, and small amounts of meat at the center of the meal. As for signaling social status, there is no better way to say, “I’m an educated, discerning person and you are about to experience an amazing dinner party!” than serving a menu from Ottolenghi.

Far from metro London, the chef’s influence has seeped into the heartland. On a recent trip to Paso Robles in Central California, a spice store had a table dedicated to Ottolenghi mainstays like dried barberries, sumac, Aleppo chiles, pomegranate molasses, cumin seed and, of course, Za’atar. The man practically invented the word! The small-town shopkeeper confided that if I bought them all, I could follow any of Yotam’s recipes without blinking an eye. “They’re not really difficult,” she explained, fondly remembering her last dinner party à la Ottolenghi. “The trick is to stock his favorite spices—all twenty of them!”

If you want to try a recipe, keep in mind the chef’s advice to a reporter for the “London Evening Standard.” When asked what to do if you are missing an ingredient, “Just leave it out,” said the chef. “I’m much less obsessed than are some people who cook the recipes.” These days, his recipes are available in the food section of the “New York Times,” where he writes a monthly column.

These days, his recipes are available in the food section of the “New York Times,” where he writes a monthly column.

As for the thorny question of his partnership with Palestinian chef Sami Tamimi, the poet Tamimi explained their relationship to The New Yorker staff writer Jane Kramer in her 2012 Ottolenghi profile in the magazine. He said that the original vision for the Notting Hill deli was totally Ottolenghi’s. “The work was his. The financial stake was his. He risked everything he had.” Tamimi summed it up by saying that he was invited in as a partner, and that “Yotam will always be the boss.”

These days Tamimi runs the restaurant kitchens, while Ottolenghi focuses on his creative projects and recipe development. He is the extrovert, a charming front man for a complicated business that includes the cookbooks, seven restaurants, various special projects including TV and specialty foods. The business is currently owned and managed by four partners—like a very small epicurean kibbutz.

By the way, for those Los Angeles restaurant hounds who want a taste, I recommend trying the downtown restaurant Bavel owned by Ori Menashe, an Israeli-born chef who channels a similar aesthetic with great style and a California spin. He also does not call his cuisine Jewish. I just like to think of it that way.

Los Angeles food writer Helene Siegel is the author of 40 cookbooks, including the “Totally Cookbook” series and “Pure Chocolate.” She runs the Pastry Session blog. During COVID-19, she shared Sunday morning baking lessons over Zoom with her granddaughter, eight-year-old Piper of Austin, Texas.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.