In Deuteronomy, we’re told that the one thing you can’t take as pledge for a debt is someone’s top millstone. This law seems archaic and meaningless, yet it speaks volumes about the pitiful state of American bread-eating habits — and gives a big clue about how we can repair it.

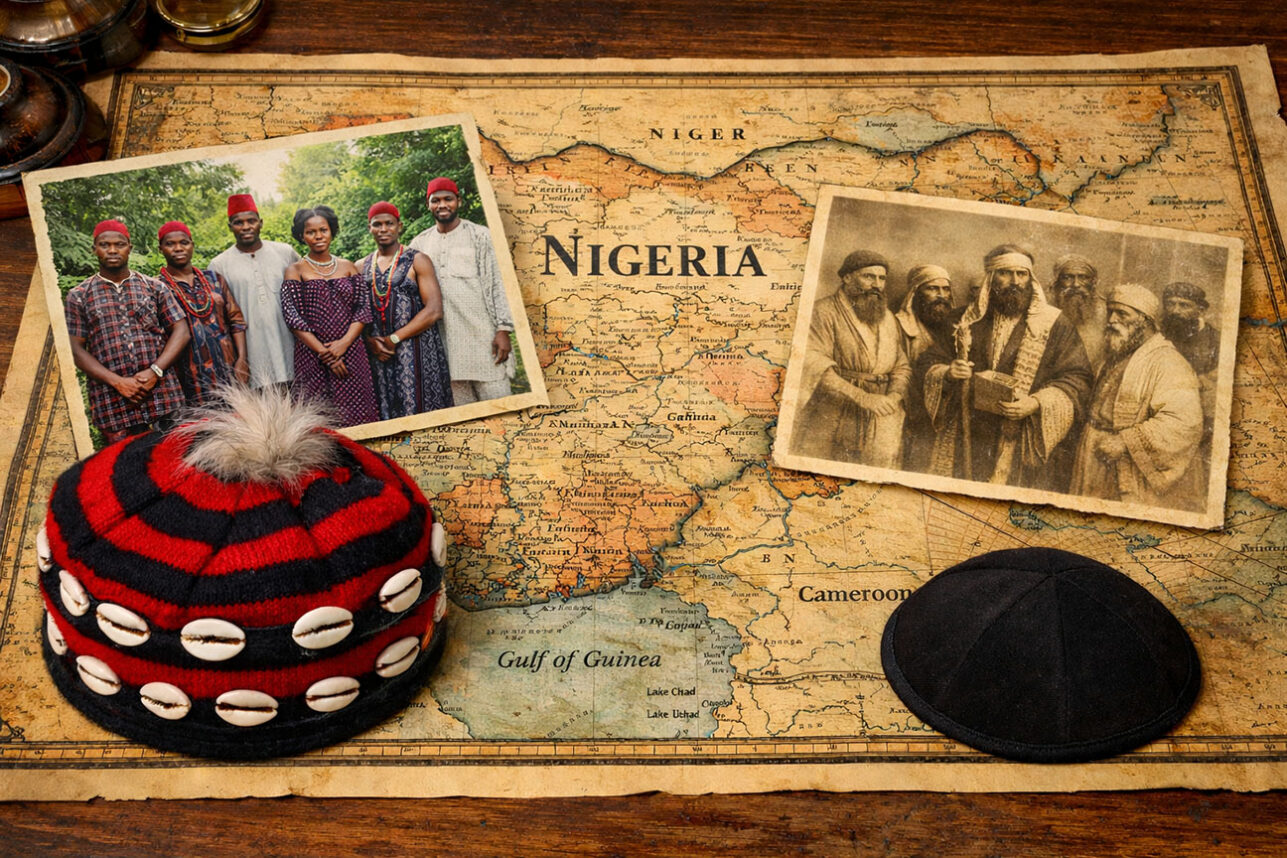

To our biblical forebears, millstones were so important that taking one as collateral left someone unable to make his daily bread. You don’t want your debtors to starve before paying you back. Bread was the staff of life, and there was no bread without milling the wheat into flour.

A mill is made by stacking two round, flat stones on top of each other. Grains are poured into a small hole drilled in the center of the top stone, and rotation crushes the grains between the stones.

Today, the vast majority of us get our daily bread from the supermarket, and the simple but critical process of milling grains has become invisible. The result is not good for the flavor of our bread — or our health.

Our daily grocery store bread generally begins as nonorganic grains, grown on government-subsidized farms, then transported many miles to huge factory mills where the grains are refined to become flour.

The refining process strips grains of their mineral- and fiber-rich bran and removes the vitamin-packed germ. This greatly lengthens shelf-life but has unintended health impacts. It turns out, we got so good at processing flour that we began to get sick as a result.

For instance, B vitamins found in wheat germ prevent pellagra, a disease that ravaged the United States in the early 1900s. These days, the government requires that white flour be enriched with vitamins; otherwise, it is imbalanced and without nutrition.

After learning all these facts, I decided to bake healthful bread for my family, using a natural yeast starter and the best organic whole-wheat flour I could buy. No more refined white flour for me! Only later did I learn I was leaving out a crucial step in the process: milling the flour myself, fresh from whole grains.

The same way an apple starts to turn brown the moment you cut it open, a whole-wheat berry starts to go bad as soon as it’s milled. Intact, a wheat berry will last decades, even centuries, and still sprout into a beautiful blade of grass. But the clock starts ticking when you break the outer seal.

The whole-wheat flour we’re used to tasting is a little bitter because the healthy oils quickly go rancid when exposed to air. I was going to great lengths to provide my family with a healthy staple food, yet I was using spoiled ingredients.

Mills have been around for thousands of years but are not found in regular stores. Digging on line, I found mills ranging from $200 to $500. So I ordered one and began my adventures in making bread with 100 percent freshly milled flour.

In those early days, I reinvented all the newbie-baker bread styles: the brick, the hockey puck and the concrete paving stone. How could I get my bread to fluff up like store-bought bread without adding white flour? There were all sorts of complicated techniques and a variety of modern additives I could buy. It was tempting to try them, but I thought again of our biblical ancestors. They couldn’t run to the store for instant yeast, dough conditioners or vital wheat gluten. There had to be a better way.

Leavening bread the old-fashioned way was not accomplished through instant dry yeast from a store shelf — instead, it occurred through the action of naturally occurring yeasts and lactic acid bacteria. The tradition of the unleavened matzo, one of the most well-known symbols of Passover, reminds us of the importance of leaven by living without it for a bit.

As a baker, I find the rules of Passover and the making of matzo fascinating because they give us clues to the differences between baking now and 3,500 years ago.

If you mix today’s refined flour and water, it can take a week of work to get a robust “leaven” from it. But mix water with freshly ground flour and you’ll discover that the yeast strains living symbiotically right on the seed begin to leaven the bread almost immediately. That could be why Jewish law still requires matzo to be baked within 18 minutes to avoid any leavening at all. Using modern, bleached, sterile flour, you have zero chance of getting any leavening action in 18 minutes — but use an organic, freshly milled flour and the process begins right away.

So I sat down with a 50-pound bag of hard, white wheat berries and my new grain mill. And drawing on what I had learned about bread baking up to that point, I set about relearning how to bake, using only wheat berries and salt water. That’s it.

After a few tries, I baked my first passable loaf of bread. Surprisingly, I didn’t even have to knead it much, if at all. It sliced easily and it tasted great. The kids even preferred it to store-bought bread.

After milling my own grain, I noticed that the bread we ate at restaurants was beginning to taste boring and flat. It’s like grinding your own coffee beans, then going to a restaurant that serves instant coffee.

Isn’t our daily bread at least as vital as our beloved morning coffee? It’s that sentiment that took me from being a user of millstones to being a merchant. Millstones became my passion, then my business. I opened The King’s Roost in Silver Lake, the first brick-and-mortar store in the United States to sell grain mills and locally grown grains in one place.

I tell my customers that using freshly milled grains will make their traditional flatbreads and crackers — even matzo — more flavorful than anything you can buy in any store or bakery. Not to mention the nutritional benefits.

Whole grains and seeds are readily available in many stores, and if you have a mill, you can make the kind of real flour that past generations enjoyed. Bypassing many of the steps in our modern industrial food system feels almost like an act of subversion — you now can buy whole grains that are grown a couple of hours from where you live, then turn them directly into food for your family. Not just breads, but cookies, cakes, pastries, tortillas and more. The possibilities are endless.

“The ceasing of the sound of the millstone was a sign of desolation,” the prophet Jeremiah tells us.

Maybe it’s time for the sound return to our homes.

ROE SIE’S 100 PERCENT WHOLE WHEAT BREAD RECIPE

This is the simplest and least processed bread I’ve seen or tasted. While it can be done with a mixer, this recipe doesn’t need one. The only ingredients: freshly milled flour, kosher salt, filtered water, and wild yeast starter (ingredients being only live yeast, whole-meal flour, and water). None of “the good stuff” is taken out of this bread. It’s a 100 percent extraction bread … which is a fancy way of saying you don’t sift out any of the bran. Keep in mind this is a guide: it works well for my whole grains and you will need to adjust a bit for the type of grains/flours you end up using.

Mix 500 grams flour, 365 grams filtered water and 12 grams salt.

Rest between 20 minutes and 4 hours at room temperature (autolyse).

Mix in 100 grams of starter.

Bulk ferment anywhere from 5 to 24 hours (depending on the temperature). Hot day? You may only need 5 hours. In the fridge? At least overnight. Periodically stretching and feeling the consistency will help develop the gluten, avoid over- or under-fermenting the dough and allow you to adjust the hydration to get the consistency you prefer. When you notice a nice jump in dough size or activity level in your dough, you’re ready for the next step.

Shape the dough for the final proof, and move to the proofing basket for 20-40 minutes (poke test).

Gently move the dough to your loaf pan, your peel, cloche, cookie sheet, pizza stone, steam oven, etc.

Slash and bake at 400 F for 45 minutes.

Transfer to rack, wait a half hour (if that’s even possible) before cutting into it. Enjoy!

Roe Sie sells do-it-yourself fermentation and bread-baking equipment (including mills) and teaches bread-baking classes at The King’s Roost in Los Angeles.