Mexican crypto-Jews not only took an active role in the cacao trade in the New World, they also secreted it into their undercover Jewish ritual life in the mid-seventeenth-century. Chocolate accompanied meals at the beginning and end of the fast of Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement). This may have been the most frequently observed of the Jewish holy days, so much so that many hidden Jews even risked writing down the exact date. The theme of atonement resonated for them, as they felt themselves constantly sinning through their public profession of Catholicism. Here are a few examples:

Gaspar Váez broke his 1640 Yom Kippur fast with drinking chocolate, eggs, salad, pies, fish, and olives.

Isabel de Rivera testified to the Inquisition on October 7, 1642, that a year before, on Yom Kippur, Doña Juana, sent “thick chocolate and sweet things made in her house.”

Around 1645 Gabriel de Granada and his family washed down their pre-fast meal with chocolate, having also dined on fish, eggs, and vegetables. Others reported that they preceded the Day of Atonement with fruit and chocolate and that they broke the fast with chocolate and similar treats.

Beatriz Enríquez, at the age of twenty-two, testified that when her husband left for long business trips, she took advantage of her sadness to hide her abstinence from chocolate and food on día grande (the big day), or Yom Kippur:

From the window she pretended to be crying over the absence of her husband and with this suffering she was able to hide from her negras (Negro servants) the fact that she ate nothing and did not drink chocolate that day.

In order not to eat on fast days such as Yom Kippur, Amaro Díaz Martaraña and her husband would stage a falling out with each other in the middle of the day. When chocolate was brought to them, they would pretend to be offended and spill it on the servants. They reconciled in the evening.

To offer chocolate at times when it was proscribed and to receive a refusal in response was to communicate through a coded language. Jews developed such sticky subterfuges to avoid being outed for drinking chocolate on Catholic fast days or for not drinking chocolate on Jewish fast days. This version of Mexican hot chocolate roots the Jewish story of chocolate drinking in the Inquisition in New Spain/Mexico. Try it at your Yom Kippur pre-fast and break-the-fast.

Mexican Hot Chocolate (a pareve version would have been used in seventeenth-century)

Ingredients:

4 ounces unsweetened chocolate

4 cups milk

2 cups heavy cream

3⁄4 cup sugar

1 teaspoon ancho chile powder (or to taste)

1 teaspoon chipotle chile powder (or to taste)

1 tablespoon ground cinnamon

1⁄2 teaspoon ground cloves

1 tablespoon vanilla extract

Instructions:

Melt the chocolate in a large bowl over a simmering pan of water. In a separate heavy saucepan, heat the milk and cream on low until hot, but not boiling. Add 3 tablespoons of the hot milk to the chocolate in the bowl and mix well. Stir the rest of the milk mixture, sugar, chile powders, cinnamon, cloves, and vanilla into the chocolate. Whisk chocolate briskly for 3 minutes, over the double boiler to thicken.

(Note: To make it less spicy, use less chile.)

Quantity: 8 servings

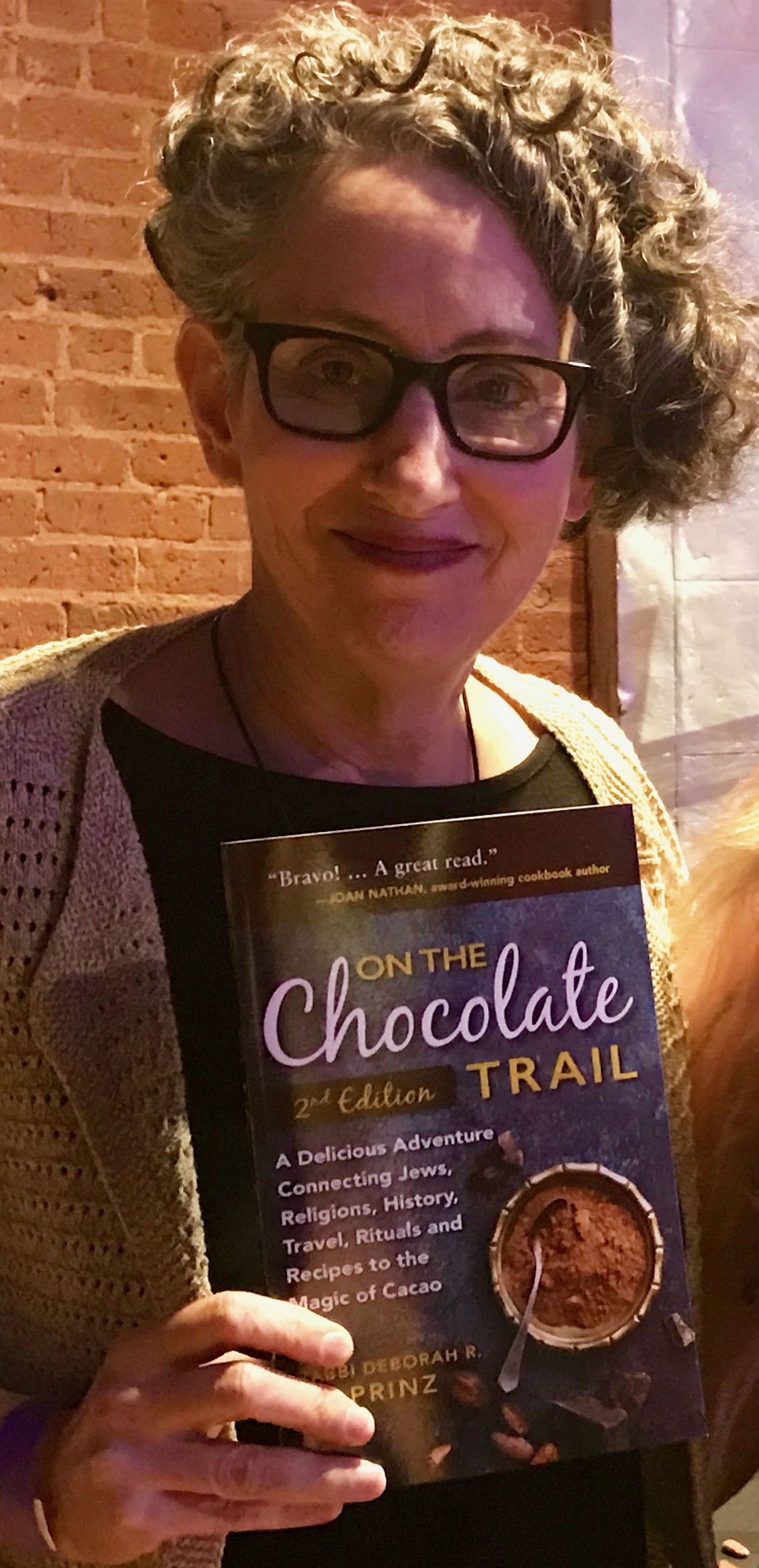

To read more about chocolate in the Inquisition see On the Chocolate Trail: A Delicious Adventure Connecting Jews, Religions, History, Travel, Rituals and Recipes to the Magic of Cacao published by Jewish Lights.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.