Photo by David Becker/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

Photo by David Becker/Getty Images for The Recording Academy The passing of Jewish music luminaries in pop, rock, classical, films, and Broadway shows will be honored at the Grammys ceremony–with its traditional In Memoriam segment–on Sunday, February 4.

With their names flashing by only for an instant, this guide provides a broader and deeper look into the incredible creative contributions of six prominent Jews in the music community who departed this past year. Their souls have ascended, their memories are for blessings, and of course, their music surely is destined to live on.

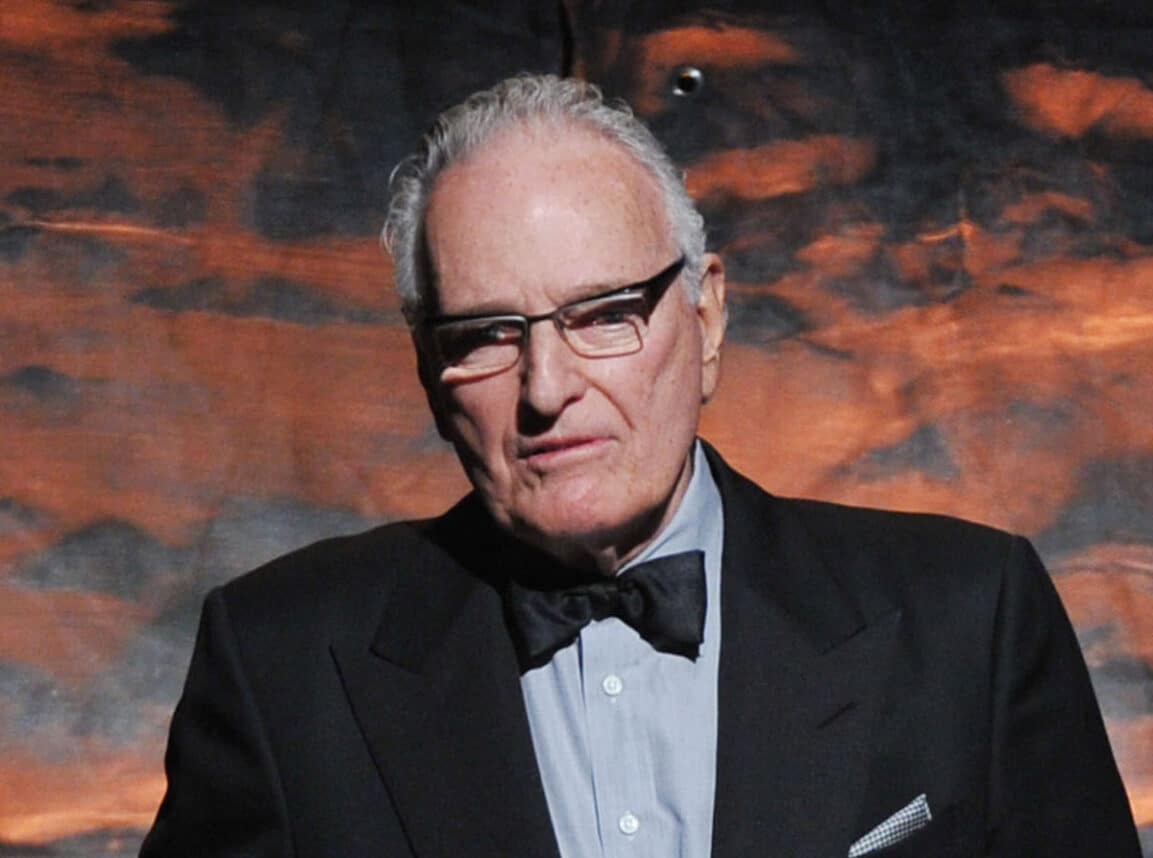

Menachem Pressler, 99

In November 1928, the men’s clothing store owned by Pressler’s Jewish parents was destroyed by Kristallnacht, the Nazi riots directed against German Jews and their businesses. Within a year, his family fled Nazi Germany for Italy, then settled in Palestine. His grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins all died in concentration camps.

The trauma for young Menachem understandably was great; he suffered from eating disorders and was in danger of starvation. But he found solace in playing piano and says that his time at the keyboard helped cure him.

With diligent practice, he became good enough to win first prize in the Debussy International Piano Competition in 1946, which was held in San Francisco. There, Pressler saw the enormous musical opportunities that he could pursue in the United States. His move came soon after, and in 1947, he took the stage for his Carnegie Hall debut.

He became an acclaimed piano soloist, touring with leading orchestras throughout the U.S., as well as Brussels, Helsinki, London, Oslo, and Paris. In 1955, he recorded a cycle of Mozart piano trios at the Berkshire festival, appearing with violinist Daniel Guilet and cellist Bernard Greenhouse. This performance was so well received that the three musicians decided to form a chamber music group, the Beaux Arts Trio, that went on to perform in hundreds of recordings and thousands of concerts. Pressler’s star in the classical musical galaxy would shine for decades, and over time, the Beaux Arts Trio expanded to include contemporary music by Charles Ives and Ned Rorem.

Pressler also became a revered teacher of new generations of piano virtuosos as a Distinguished Professor of Music and Charles Webb Chair at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music. This aspect of his life, which extended for more than a half-century, was equally rewarding.

It was especially poignant when Pressler returned to Germany in 2008 to perform on the occasion of the 70thanniversary of Kristallnacht. Aged 90, in December 2014, he made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic at their New Year’s Eve concert. This performance was televised live throughout the world, something that was unimaginable when the Presslers fled their native Germany. The darkness of life then seemed to have no end, but Pressler’s music throughout his storied career brought back light to the cherished memories of those whose lives had been tragically cut short.

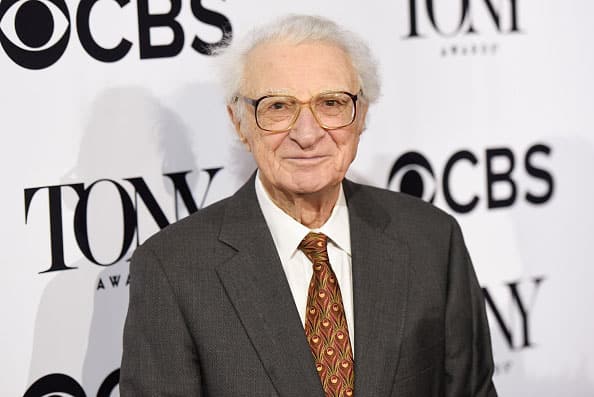

Sheldon Harnick, 99

We all can hum the memorable tunes composed by Jerry Bock. But it is the lyrics to the songs that make all the difference because they allow us to sing them with a range of emotions. If I Were a Rich Man. Sunrise, Sunset. Matchmaker, Matchmaker. And perhaps the greatest Jewish anthem of all time: Tradition.

By the time Sheldon Harnick wrote the words to these songs in Fiddler on the Roof, he already had won a Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award with Bock for their score to the 1959 Broadway musical, Fiorello! But the expectations for Fiddler were relatively low since few could imagine that audiences beyond the Jewish community would flock to a story based on Tevye the Dairyman and other tales by Sholom Aleichem, set in the Pale of Imperial Russia at the beginning of the 20th century.

The exquisite quality of the story, songs, and direction by the acclaimed director and choreographer Jerome Robbins could not be denied. The set design by Boris Aaronson was in the style of Marc Chagall’s paintings. Zero Mostel as Tevye was a force of nature on stage. And who could forget Bea Arthur as Yente the Matchmaker or, yes, Bette Midler as daughter Rivka?

Those who subsequently sang Harnick’s Fiddler lyrics, too, are a diverse group of talented Jewish performers. Among the actors who have assumed the role of Tevye on stage are Chaim Topol, Herschel Bernardi, Theodore Bikel, Leonard Nimoy, Danny Burstein, and Harvey Fierstein.

The original Broadway production opened in 1964 to high praise and critical acclaim. It became the first musical theatre run in history to surpass 3,000 performances won nine Tony Awards, including another one for Bock and Harnick. And unlike most Broadway shows, it also was highly profitable for the handful of investors who knew that the story of Fiddler was both Jewish and universal, touching upon themes of family and a longing to feel at home for generations.

The show remains an international hit sixty years on. Fiddler has played to sold-out audiences in Europe, South America, Africa, and Australia; it remains the longest-running musical ever seen in Tokyo. According to Broadway World, Fiddler has been staged “in every metropolitan city in the world from Paris to Beijing.” The number of summer camp, school, and community theatre productions is nothing short of staggering, with over 500 amateur productions a year in the US alone. Its popularity continues in full force, including the acclaimed 2022 off-Broadway revival by the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene, directed by Joel Grey.

Sheldon Harnick also knew that his lyrics, however well-known, could be adapted to the needs of the times. Since Sunrise, Sunset has become such a staple at Jewish weddings, Harnick realized that it was appropriate in 2011 to write a version with minor word changes that would be suitable for same-sex weddings. For example, male couples now could be serenaded with “When did they grow to be so handsome.” The wordsmith himself knew that the idea of Tradition would mean more if it remained relevant for all in contemporary times.

Burt Bacharach, 94

Burt Bacharach was a man of all media: composer, arranger, producer, pianist, conductor, recording artist, and host of memorable television specials with Barbra Streisand and others. Songs he co-wrote with various lyricists have been recorded by more than a thousand artists, making him one of the most successful tunesmiths of popular music from the 1960s on.

From Dionne Warwick and The Carpenters to Herb Alpert and Luther Vandross, Bacharach’s name is associated with music that’s more sophisticated than three chords in 4/4 time. It filled a middle-of-the-road gap of Broadway, pop, and easy listening for the generation just before the British Invasion and the era of the singer/songwriter began, and kept going with new writing partners such as Elvis Costello.

Burt Bacharach’s ascendance came at a time when Top 40 AM radio was the currency of the day for a songwriter or performer. Now, satellite radio channels can get sliced down to not just a single genre, but sometimes a specific artist. Spotify and Pandora narrow the possibilities even further.

In contrast, during the 1960s, the Top 40 hits chart could include songs from almost anyone as long as there was a large audience for it. Music from rock groups like The Beatles, crooners like Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr. and Dean Martin, the Singing Nun, and an occasional country singer flowed seamlessly on the same radio station. Bacharach’s songs with Hal David had a prominent role in that broad roster, excelling with a rare level of complexity and sophistication.

His string of hits with David started in earnest when he met singer Dionne Warwick at a recording session. He recognized she had the musical chops to handle the intricate melodies, tricky phrasing, and time changes that were the team’s signature.

The trio crafted hits including Say a Little Prayer for Me, I’ll Never Fall in Love Again, Walk On By, The Look of Love, Alfie, Always Something There to Remind Me, and Do You Know the Way to San Jose? Their collaboration was one of the most successful in pop music history. For movies, Bacharach co-wrote Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head and Arthur’s Theme, both Oscar winners.

He rarely discussed the Jewish background of his parents or himself, but his commitment to the principle of tikkun olam clearly was evident in That’s What Friends Are For, which he wrote with his then-wife, lyricist Carole Bayer Sager. His work in making this a mega-hit had a true and lasting impact well beyond the song itself.

Their close friend Elizabeth Taylor, at Dionne Warwick’s suggestion, asked if they would allow the song to be used in a special way during the height of the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s. Little was known about the disease, and virtually no government research money had been allocated, even though thousands were dying rapidly.

Bacharach and Sager agreed and made sure that all of the song’s royalties would be directed to the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR), which had appointed Elizabeth Taylor as Honorary Chair. The recording artists on that 1985 single— Dionne Warwick, Stevie Wonder, Elton John, and Gladys Knight–also directed their royalties to this charity.

As a result, this recording raised more than three million dollars for amfAR. Equally important, its prominence on radio playlists made the song an enduring anthem that would supercharge public recognition of the need to help combat the global AIDS epidemic.

Jerry Moss, 88

Has there ever been a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee who also has been honored by the Southern California Jewish Sports Hall of Fame?

Recording executive Jerry Moss is the only one who could claim these two honors. Moss’s career started in the 1950s by promoting records like the hit 16 Candles by The Crests, one of the first racially and gender-mixed doo-wop groups. However, his business acumen led him to think bigger about the possibility of his own independent record company.

A&M Records was the start-up venture that Moss launched with trumpeter Herb Alpert in the early 1960s. It became a powerhouse by nurturing a large roster of superstar artists such as Alpert’s Tijuana Brass, The Police, Janet Jackson, Quincy Jones, The Carpenters, Burt Bacharach, Cat Stevens, Carole King, Sheryl Crow, Joan Baez, and Peter Frampton.

Moss oversaw financial, marketing, and record distribution concerns, with Alpert focusing on the creative side by working closely with the musicians on the label’s roster. Alpert said Moss had great integrity and they never had more than a handshake deal. Those were priceless assets.

They also proved to be highly profitable for these close business partners and friends. They sold A&M Records to PolyGram Records for an estimated $500 million in 1989 (more than $1.2 billion in 2024). This enabled Alpert and Moss to become dedicated philanthropists for decades to come. Jerry Moss donated $25 million to the Music Center in downtown Los Angeles, and millions more in the areas of education and healthcare. Ever the businessman, he also owned an art collection with works by Picasso, Magritte, and Warhol, a portion of which was auctioned off for $60 million.

As for his induction into the Southern California Jewish Sports Hall of Fame, his successes in the music industry also allowed Jerry Moss to indulge his passion as a horse breeder, a notoriously expensive undertaking. He went on to win the Kentucky Derby in 2005 with his horse Giacomo, named after one of the musician Sting’s sons. Sting laid down a $1,000 bet on the horse with 80-to-1 odds in the Derby and jokes that he’s still living off the proceeds today.

Moss scored big again in the Breeders’ Cup Classic four years later with Zenyatta, named for an album by The Police–the group that made Sting famous and helped propel A&M Records as a force to be reckoned with in the music industry.

Cynthia Weil, 82

The epicenter for American pop music in the late 1950s and 1960s—before the Beatles and the British Invasion took the country by storm—was the Brill Building at 1619 Broadway in New York City. There, a group of largely young Jewish musicians toiled away to churn out dozens of chart toppers that have stood the test of time.

Reviewing the Brill Building roster today seems fantastical; how could so much talent be squeezed into a few floors of a single location in Manhattan? Neil Sedaka was there, as was Neil Diamond, Marvin Hamlisch, and even Paul Simon, using the name Jerry Landis when he was in a duo with Art Garfunkel called Tom and Jerry.

The most competitive writing teams used the success of their rivals to see who could turn out the next big hit on AM radio. The story is well told in the Broadway show Beautiful: The Carole King Musical. Two young married couples, King (née Carol Klein) and Gerry Goffin, and Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann, became lifelong friends and musical rivals. As Carole King recalled to Simon Frith in The Sociology of Rock, “Every day we squeezed into our respective cubby holes with just enough room for a piano…You’d sit there and write and you could hear someone in the next cubby hole composing a song exactly like yours.”

The melodies may have sounded similar, but the lyrics clearly were distinctive. And as a pop lyricist, Cynthia Weil emerged as Brill Building royalty, working with Mann (and occasionally other musical partners) to produce great songs for six decades.

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s 2020 tribute when Mann and Weil were inducted into that hallowed institution captured the special impact of her lyrical gifts: “With Weil writing the words and Mann the music, they came up with a number of songs that addressed such serious subjects as racial and economic divides (Uptown) and the difficult reality of making it in a big city (On Broadway). Only in America tackled segregation and racism [causing it to be recorded by Jay and the Americans rather than The Drifters, who were deemed to be too controversial as a black group to deliver that sober message]. We Gotta Get Out of This Place [a smash for The Animals], became an anthem for the Vietnam soldier, antiwar protesters, and young people who viewed it as an anthem of greater opportunities.”

And her lyrics for You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’, with music by Barry Mann and Phil Spector, reached a stratospheric level of airplay; Broadcast Music, Inc. ranked it as the most-played song on American radio and television in the 20th century, and the Recording Academy honored it as the Song of the Century.

Cynthia Weil’s words were heartfelt and soulful. Perhaps the best example was a song recorded by Linda Ronstadt that she co-wrote with Mann and James Horner, which was a double Grammy winner in 1988. Cynthia’s father was Morris Weil, a furniture owner and son of Lithuanian-Jewish immigrants. The animated musical An American Tail tells a similar Jewish story about Fievel Mousekewitz and his family as they emigrate from Russia to the United States. After losing them upon arrival, Fievel then must find a way to reunite with loved ones.

Somewhere Out There is both a cry of despair and an ode to hope. Cynthia Weil uniquely could capture that all in about three glorious minutes.

Robbie Robertson, 80

One of the ironic things about The Band’s Civil War-themed song The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down is that it was written by a Canadian who was part Cayuga and part Mohawk. But this songwriter’s music had a true feel of the American spirit. His first name was Jaime, but he was known to music fans as “Robbie” Robertson and he was one of the creative forces behind The Band.

Robertson was obsessed with the guitar at an early age. His first important exposure to making music was when visiting relatives living on the Six Nations reservation near Toronto, Canada, where he had spent his early years.

Aged twelve when his mother was getting divorced, she revealed a big surprise in his lineage. The man he called “Dad” up until then was not his natural parent. That day, he learned his biological father was actually a Jewish-American gambler who had been killed years earlier in a hit-and-run accident.

By the time he was fifteen, Robbie was already a good enough musician to leave home to join Ronnie Hawkins and The Hawks for their North American club dates. With his background well known among friends by then, Hawkins once commented, “Robbie’s real dad was a Hebrew gangster.”

The backup group broke away from Hawkins and eventually changed their name to simply The Band. They provided the music for Bob Dylan’s first electric tour where they were roundly booed, moved to the Woodstock area, and had Beatle George Harrison and guitar legend Eric Clapton yearning to join.

Some of Robertson’s other best-known songs were Up on Cripple Creek, Stage Fright, and Life is a Carnival. Vying with “Dixie” for his best-known song was The Weight, about a trip to Nazareth, the Pennsylvania location of the Martin Guitar factory that produced the instrument that he used in writing the song. The Weight has been recorded at least 25 times by artists ranging from the Staple Singers and Aretha Franklin to John Denver and Joe Cocker.

The Last Waltz, a 1978 feature-length documentary of The Band’s final concert, was directed by Martin Scorcese. It helped to open the second phase of Robertson’s career. He and Scorcese worked on the film together and became friends and collaborators. Robertson went on to score or serve as music supervisor for many films with the noted director, beginning with 1980’s Raging Bull and ending with 2023’s Killers of the Flower Moon, for which he has been posthumously nominated for an Oscar.

Robertson stayed connected to his indigenous roots. In 1994, he recorded a solo album, Music for the Native Americans. It showed his passion for music was sparked by his upbringing on the Six Nations Reservation and marked the first time he had written music inspired by his Mohawk heritage.

He nurtured his Jewish roots, too, especially by forging a close relationship with his late father’s two brothers, Morris and Nathan, and with The Band’s manager Albert Grossman, who recognized Robertson’s talent in the early days when The Band took up residence at a house he rented for them—Big Pink.

Stuart N. Brotman and Bob Males are music aficionados who have spent decades– as friends since their Bar Mitzvahs–sharing with each other their vinyl singles, albums, CDs, iTunes playlists, and Spotify selections. Their tastes have become more eclectic with each passing year, and their appreciation for Jews who have shaped American musical history continues to grow.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.