One year, at the intense and highly competitive quiz night at the conference for the Association for Jewish Studies (we academic types really know how to party), I wrote the wrong answer to the literary softball question: “Who wrote ‘To be a Jew in the 20th Century’?” The answer was Muriel Rukeyser. (My office is now next door to a Rukeyser expert, and I’ll never forget it!). The quizmaster, a fellow literary scholar, castigated me. How could I call myself a scholar of Jewish American writing and not know who wrote the poem?

The problem was this: I never read poetry.

A couple of months ago, I was asked to review a book in verse and found myself about to say no. Since studying the standard Chaucer/Shakespeare/Donne/Herbert/Marvell/Milton in university, I have picked up exactly one book of verse: Rupi Kaur’s “Milk and Honey.” I have in my head the idea that I just don’t “get” poetry like I don’t “get” cetology (which put me off reading “Moby Dick” for many years, but, alas, that’s another story).

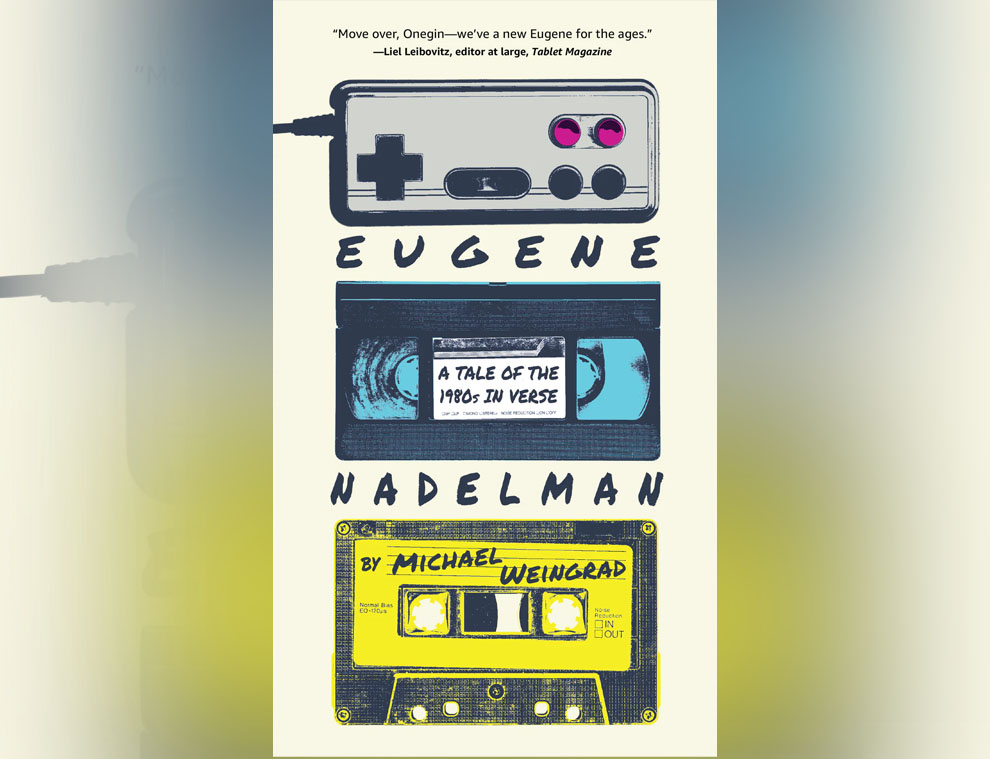

But wow, did I love Michael Weingrad’s “Eugene Nadelman: A Tale of the 1980s in Verse.” It is hilarious. If, unlike me, you’re a big fan of poetry, come to it for the form: Weingrad assiduously applies Alexander Pushkin’s iambic tetrameter and rhyme scheme of AbAbCCddEffEgg throughout the book. According to the book’s narrator, who, like Pushkin’s narrator in “Eugene Onegin,” is far more knowing than the protagonist and interrupts the story regularly, he is not the first to make such an attempt. He cites Indian author Vikram Seth (“The Golden Gate,” 1986) and Israeli author Maya Arad (“Another Place, A Foreign City,” 2003) as those who have successfully employed Pushkin’s rhyme scheme in their novels, admitting, “others have used Alexander/Sergeivich Pushkin’s elegant/Design with more accomplishment.” Nonetheless, the author/narrator of “Eugene Nadelman” has one advantage over his literary peers: He is more religious about Pushkin’s “regular iambic trot.” As the lines above attest, he is religious about them even when they result in abrupt line endings (“elegant”), making the book rather a challenge to read aloud (though maybe not for the more poetically inclined). But that’s only one of the ways the poetry is playful. Expect the narrator to break the fourth wall, sneak in an ode to his brother, and provide readers with a “do-it-yourself sonnet” (he gives you prompts).

If, like me, you appreciate funny Jewish stories and nostalgia for the ’80s, when the country was divided less on blue and red than Beta or VHS, Casey Kasem’s voice reigned supreme, and Saturday morning cartoons were the shul of a generation, do do do come to this book for the content! Very loosely following the plot of Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin”—there’s a girl, there’s a duel, there’s a breakup—“Eugene Nadelman” showcases a hero who is a super-nerdy Dungeons & Dragons and Castle Wolfenstein-loving kid who, during a game of Spin the Bottle at a cousin’s bar mitzvah, meets the girl of his dreams. To show off his prowess and impress said girl, he enters a duel (in D&D, obviously—we are treated to a long passage within the game). The duel is with one of his BFFs, and it ruins their friendship. Then he’s off to sleepaway camp, apart from his girlfriend, who warns: “You’d hate it, Gene. The food is crappy./The other kids are kind of JAP-y.” Under the watchful eye of madrichim, eating at the chadar ochel, playing Holocaust games (“At one point counselors are enlisted/To dramatize the Jewish plight/And chase them through the woods at night”), Eugene makes a foolish decision. As to what happens as a result, you’ll have to read the book to find out.

Weingrad is a true talent, and this book is a joy. I ate up the reflections on Jewish life, adolescent angst and fickleness, and the vivid depictions of Philadelphia and summer camp. I found the insertions of Hebrew and Yiddish words and phrases clever and unintrusive, and the snide remarks from the future (“Just wait until the internet,” he says of/to the teenagers discovering the curtained-off section at the back of the video store) in perfect proportion to the ’80s narrative. It’s possible Weingrad has converted me into a lover of verse!

Karen Skinazi, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of “Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.