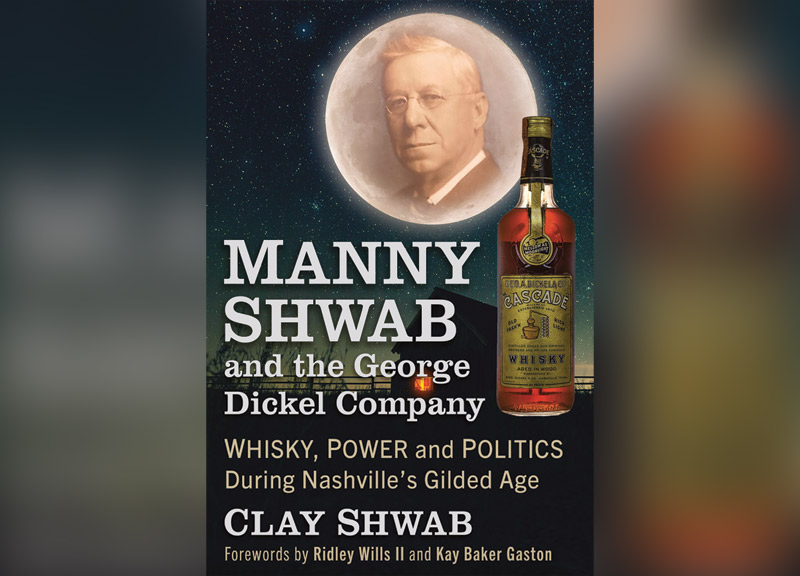

Many years ago, Jack Daniel’s was not the most popular Tennessee whiskey. Instead, it was Cascade Whiskey, which was known as being “mellow as moonlight.” The man behind it, V.E. “Manny” Shwab, was following in the footsteps of his father, Abraham Shwab, an immigrant and wine and spirits importer, during a time of Prohibition, when Tennessee was becoming a “dry state.”

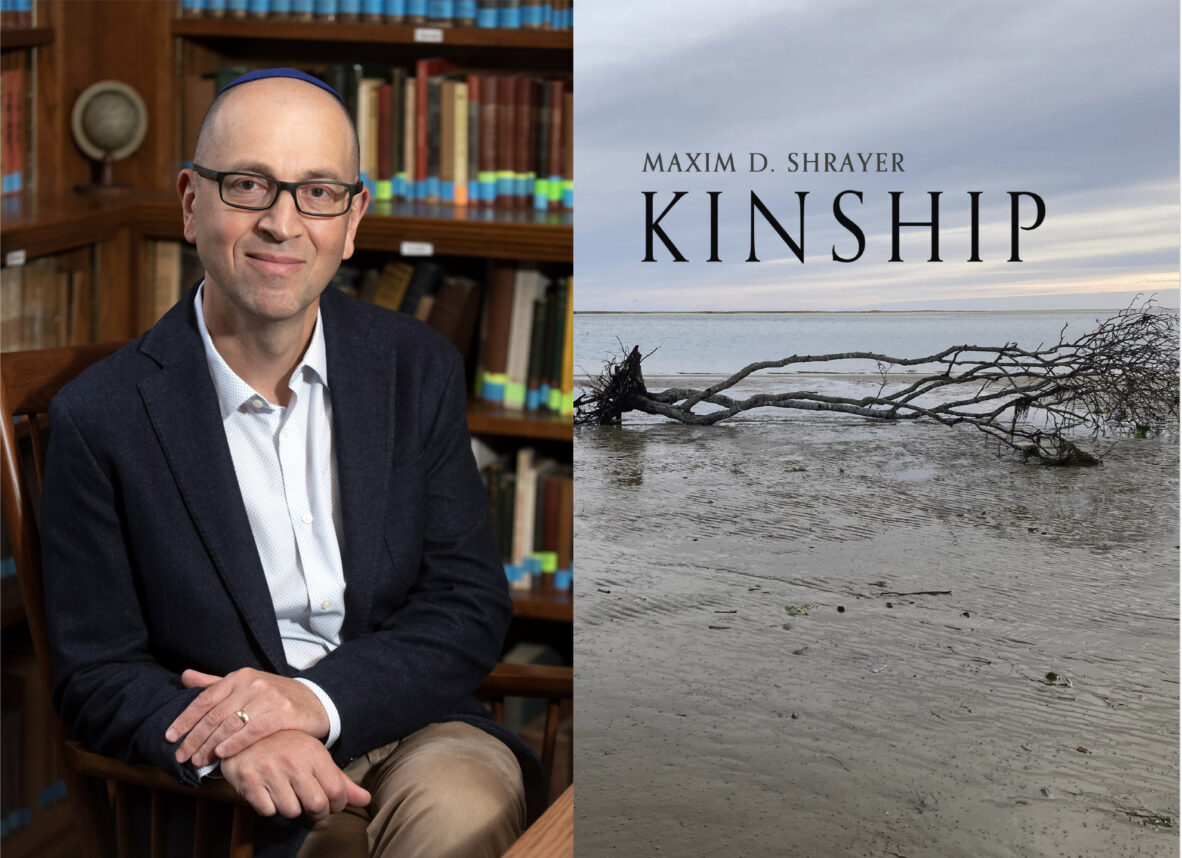

In his new book, “Manny Shwab and the George Dickel Company,” author Clay Shwab, great-grandson of Manny, gives a fascinating historical look at the man behind George Dickel, the alcohol business in the U.S. and the discrimination that his family faced for being Jewish.

Throughout the 1800s, the Shwabs made their fortune smuggling medicine, gray caps, weapons and whiskey through occupying Union lines, and they convinced George Dickel, a German immigrant who came to Nashville in 1844, to enter the liquor business after the Civil War — perhaps to launder their money.

Throughout the 1800s, the Shwabs made their fortune smuggling medicine, gray caps, weapons and whiskey through occupying Union lines, and they convinced George Dickel, a German immigrant who came to Nashville in 1844, to enter the liquor business after the Civil War — perhaps to launder their money.

In 1919, when the 18th Amendment establishing national prohibition was passed, Shwab owned the Cascade Whisky brand, the distillery and the company that distributed it, George A. Dickel & Company. Cascade gained a reputation as the most valuable distillery in the state. However, the Shwab family sold the business in 1937 after the repeal of prohibition because the wealthy family members thought that “owning a liquor company was not socially acceptable,” according to Clay.

The Jewish Journal sat down with Clay to discuss “Manny Shwab and the George Dickel Company,” which is out now in paperback. This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Jewish Journal: Why did you decide to write this book?

Clay Shwab: My son ran across Chuck Cowdery’s whiskey blog. The New York Times had declared Chuck “the dean of American whiskey writers.” He was bemoaning the fact that whiskey distilleries were not promulgating their true, rich histories. As an example, he wrote that the owner of George Dickel was promoting a “Keebler Elf” image of Dickel, the man, and that surely there were some Shwabs who would like to correct the record. I qualified as a Shwab, so that planted the notion to be more serious about the research.

I became fascinated by what I was learning about V. E. “Manny” Shwab, and about his internationally famous Cascade Whisky. When on a trip to London, our Uber driver, a recent immigrant from Croatia, asked where we were from. When I answered, “Tennessee,” he exclaimed, “Elvis and Jack Daniel’s!” The thought that, had our family retained it, George Dickel could have been so synonymous with Tennessee that a Croatian Uber driver would have known it, struck a nerve.

“I became fascinated by what I was learning about V. E. ‘Manny’ Shwab, and about his internationally famous Cascade Whisky.” – Clay Shwab

I was learning that there was much more to Manny than Cascade whiskey. He had become the richest man in Nashville, one of the richest in the South, and probably the most powerful, albeit notorious, man in Tennessee politics. In addition to his Dickel company and Cascade whiskey, he was a director for three railroads and four banks, a founder and owner of the city’s telephone company and its electric company, dozens of downtown properties, saloons, an early car dealership, and much more. But surprisingly, there was no mention of him in the various histories of the state.

JJ: What challenges, if any, did Manny face because he was a Jew?

CS: During the Civil War, the family was actively engaged in smuggling through the Union lines in Nashville to Louisville, Knoxville and Atlanta. According to the provost judge assigned to Nashville, their operations became “impossible to stop.” It was estimated that they were earning the equivalent of $412,000 a load, making multiple runs in false bottom wagons every week. Jewish smuggling became such an issue that in December 1862, Grant issued his Order No. 11, declaring that all Jews were to abandon their property and immediately leave the “western front”—Mississippi, Tennessee and Kentucky. A few weeks later, Lincoln heard the order and, incensed, revoked it.

JJ: What do you hope people get out of your book?

CS: I intend it to be an introduction to a highly successful entrepreneur who had a profound impact on Tennessee politics, modernization and whiskey. And I hope readers gain an appreciation and respect for the intrepid Jewish immigrants of the 19th century. Manny’s father Abraham was a 22-year-old Alsatian Jew who came to this country alone and with no contacts. He helped establish the original Jewish congregations in four major cities, becoming president of several, creating successful businesses in each, while navigating an unfamiliar culture that was less than accepting. His family had a significant impact in politics, business, theater and music. His son, a Confederate soldier who died in the war, was the first Jew buried in Knoxville, Tennessee, necessitating the founding of the city’s first Jewish cemetery, and his daughter was Knoxville’s first Jewish bride.

I would encourage anyone who might even suspect that they have Jewish relatives who immigrated to the U.S. in the 19th or early 20th century to seriously research that history. It was so rewarding and inspirational to learn the successes and challenges of these intrepid family members. The depth and value of their bonds, both familial and communal, probably necessitated by the perception of their “foreignness” due to their culture and religion, is a history worth uncovering and remembering. It will make you proud.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.