Many American Jews have long considered Israel a nice place to visit – but they wouldn’t want to live there. As Israel flourishes, outscoring America on the international happiness index, the reasons for this reluctance keep vanishing. But military service remains one of Israeli life’s most daunting elements. Few American Jews would trade their student IDs for IDF dogtags – even fewer would consider serving post-college with a bunch of 18-year-old Israelis. Ben Bastomski’s willingness to make that leap – after graduating from Brown University – provides the central dramatic tension in his charming, compelling memoir, just published by Delphinium Books, “As Figs in Autumn.”

Unlike many military memoirs, rather than ending tragically, this book begins in death. In February 2010, a drunk driver near the Brown campus killed the author’s childhood friend, Avi Schaefer. Avi and Ben had just reunited months earlier, three years after Avi began serving as a lone soldier with his twin brother Yoav, in the Israel Defense Forces, Tzahal, before enrolling at Brown.

The irony of surviving three years in Israel’s counterterrorism unit only to be run over by a car in college, intensified the heartbreak. So, to honor his 21-year-old friend, after graduating Ben also enlisted as a lone soldier. This profound act of forever-friendship left most people in Ben’s life thinking he was nuts. And, as the book demonstrates, this young, sensitive idealist had no idea what he was getting into.

His memoir explores the many differences between Israeli and American life in general, along with the peculiarities of IDF service itself. It’s also a useful primer for lone soldiers-to-be, or any prospective recruits. You learn tricks of the trade, like keeping “Johnson’s baby power on hand” for long marches, and the realities of army life, like the fact that you can taste the difference when the army cook actually cares about the soldiers – having been sidelined from combat by injury.

The title “As Figs in Autumn,” captures the book’s harmonious and interlocking sensibility. As still happens, even in high-tech, ever-modernizing Israel, various Israelis “adopt” Ben in old-school fashion. The first, Eli, a “family friend twice removed who had not ever known my name, took me in and gave me warmth, light, and shelter befitting a native son.”

Before Ben enlists, Eli reads him a Hebrew poem, “A Man in His Life,” translating it into English spontaneously. The majestic poet Yehuda Amichai envisions each man dying “as figs die in autumn, shriveled and full of himself and sweet, the leaves growing dry on the ground, the bare branches already pointing to the place where there’s time for everything.” Amichai – and through his book, Ben – challenge us to think about how we can make our little time on Earth most meaningful.

Before Ben enlists, Eli reads him a Hebrew poem, “A Man in His Life,” translating it into English spontaneously. The majestic poet Yehuda Amichai envisions each man dying “as figs die in autumn, shriveled and full of himself and sweet, the leaves growing dry on the ground, the bare branches already pointing to the place where there’s time for everything.” Amichai – and through his book, Ben – challenge us to think about how we can make our little time on Earth most meaningful.

This first-time author has a keen eye for detail and tells a good story. He also loves language. Ben’s foreign ear, for example, delights in the linguistic overlap between “neshek,” Hebrew for weapon, and “neshika,” kiss.

“The two,” he writes, “are attached at the hip, a mere molecular twist apart. When I discovered this twinning in the thralls of basic [training], it was perverse to the ear—but by the time I had surrendered my rifle, it was an unvarnished truth.” Beyond appreciating the irony, Ben, who became a trained sharpshooter, teaches non-Israelis every Israeli soldier’s prime directive: that misplacing your weapon is “among the more contemptible atrocities a Tzahal soldier may commit.”

Ben peppers the text with everyday Israeli expressions and that bizarre argot, Tzahal-speak, a barrage of idioms and acronyms. Providing that insider’s guide, experientially, emotionally, and linguistically, this glimpse into this alternate universe is what makes the book most compelling.

I never served in the IDF, but my four children have. When they were drafted, I knew they would be risking life and limb for their country and our people. I also appreciated the contrast between the absolute freedom and relatively-low stakes of my own academic life, and the many ways they uncomplainingly sacrificed their privacy, their autonomy, and that devil-may-care insouciance that can be so enriching during young adulthood.

Ben most appreciates that stretch – after serving. “I was free now,” he writes, “entitled not just to live my life as I wished, but to keep it.” Upon being discharged, this seems “the surest difference between soldier and citizen. To be sure, a citizen’s profession may impose myriad restrictions or even hazards to his life—but only the soldier waives the lawful right to have his. Soldierhood, at bottom, is a candidacy for death on behalf of the citizen, to whom he has allowed a mortgage on his very breath.”

That insight leads to his thought-provoking definition of a demobilized soldier as someone being “returned” to “his life’s full possession.”

As a father, I discovered another, unexpected dimension to the high costs our kids pay for having the persistent enemies we do. What I didn’t realize until I witnessed it was just how crushing it can be to be a line worker at such a tender age in what I now think of as “IDF Inc.”

Armies are complex bureaucracies. Military life involves being managed second-by-second, often by kids themselves, and far too often by petty tyrants of all ages. The “chain of command” is an apt phrase. Shelving your freedom, your creativity, your individuality, while kowtowing to superiors, is hard for anyone. It’s especially trying for an American volunteer parachuting into this foreign culture and accepting this unexpected, alternative, burden, with minimal preparation – even as many friends back home continue to indulge their every whim.

Fortunately, in most cases the resulting character-building payoffs more than compensate for what you surrender in career-development and personal comfort. And, as this book proves, all the sweat and stress and strain doesn’t prevent soldiers, including Ben, from having plenty of fun with their band of brothers every time they’re on leave.

This book also uncovers the secret to what Israelis call “sherut mashmaooti” (a meaningful service)– it’s your fellow soldiers. Blessed, occasionally, by wise and reasonable commanders, while always cocooned by supportive and fun-loving comrades, Ben builds a new family-in-arms. Having a common mission and certain shared values helps. But the key is in the chemistry they develop amid their intertwined fate, morning, noon, and night.

This otherwise clear, philosophical and captivating book concludes somewhat ambiguously. The talented author makes it into Harvard Law School. But, torn, he bursts into tears one day during Civil Procedure class, and fears becoming a “colorless and flaccid” big-time partner enslaved to “dry” work and super-rich clients quibbling over pocket-change to them. He ends the book with a return visit to Israel.

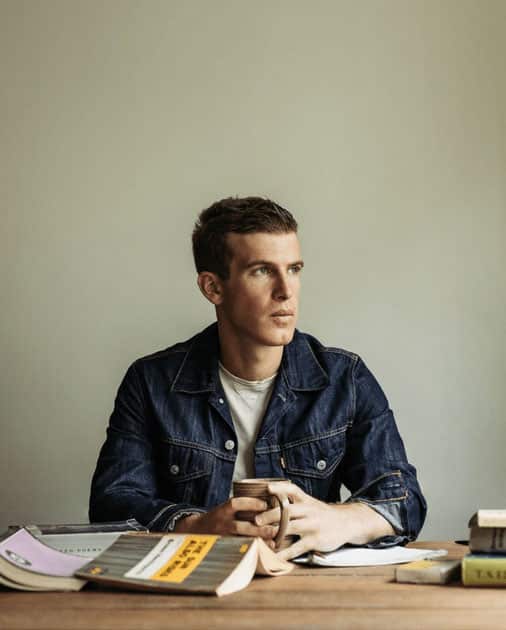

The Author’s Note says that Ben “moved to Santa Monica, CA to practice law after graduating from Harvard Law School in 2015. In the years since, Ben has become an accomplished civil litigator, while pursuing a parallel career as a fashion model with a Los Angeles talent agency. He has recently returned to live in Israel.”

I wasn’t looking for a cliche Zionist ending, but perhaps a little more closure. Whether or not Ben moved to Israel or decided to stay in America, we, the readers, and the story itself, would have loved to hear more about why he did what he did. With the “do I or don’t I” make Aliyah question hovering throughout the book, leaving it unresolved or unexplained leaves us wanting more.

Of course, finishing a 244-page memoir by a rookie author, and hungering for more, exposes this “complaint” as a great compliment. At this moment, with so many lonely, alienated, drifting young people, living in angry, mistrustful, polarizing democracies, this book is a welcome balm. It’s an ode to friendship, community, and common purpose. It’s a chronicle of character, trust, patriotism, and unity. It exudes love of the land, of the Jewish state, of the Jewish people, and of humanity. All of that makes “As Figs in Autumn” a timeless celebration of Zionism and Israeliness at their best – wherever the author chooses to live.

Gil Troy is the editor of the new three-volume set Theodor Herzl: Zionist Writings, the inaugural publication of The Library of the Jewish People (www.theljp.org).

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.