Don Lattin knows from religion. For decades he was the “God beat” reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, writing about all sorts of religious matters: from flying in the Pope’s plane with the Pope, to spending the night in a teepee ingesting magical potions with a Native American holy man, to interviewing Jewish scholars in Jerusalem.

And Lattin also knows from psychedelics. Several of his books — “The Harvard Psychedelic Club,” “Distilled Spirits” and “Changing Our Minds” — recount how powerful mind-altering substances, and the people who ingested them, have changed our world.

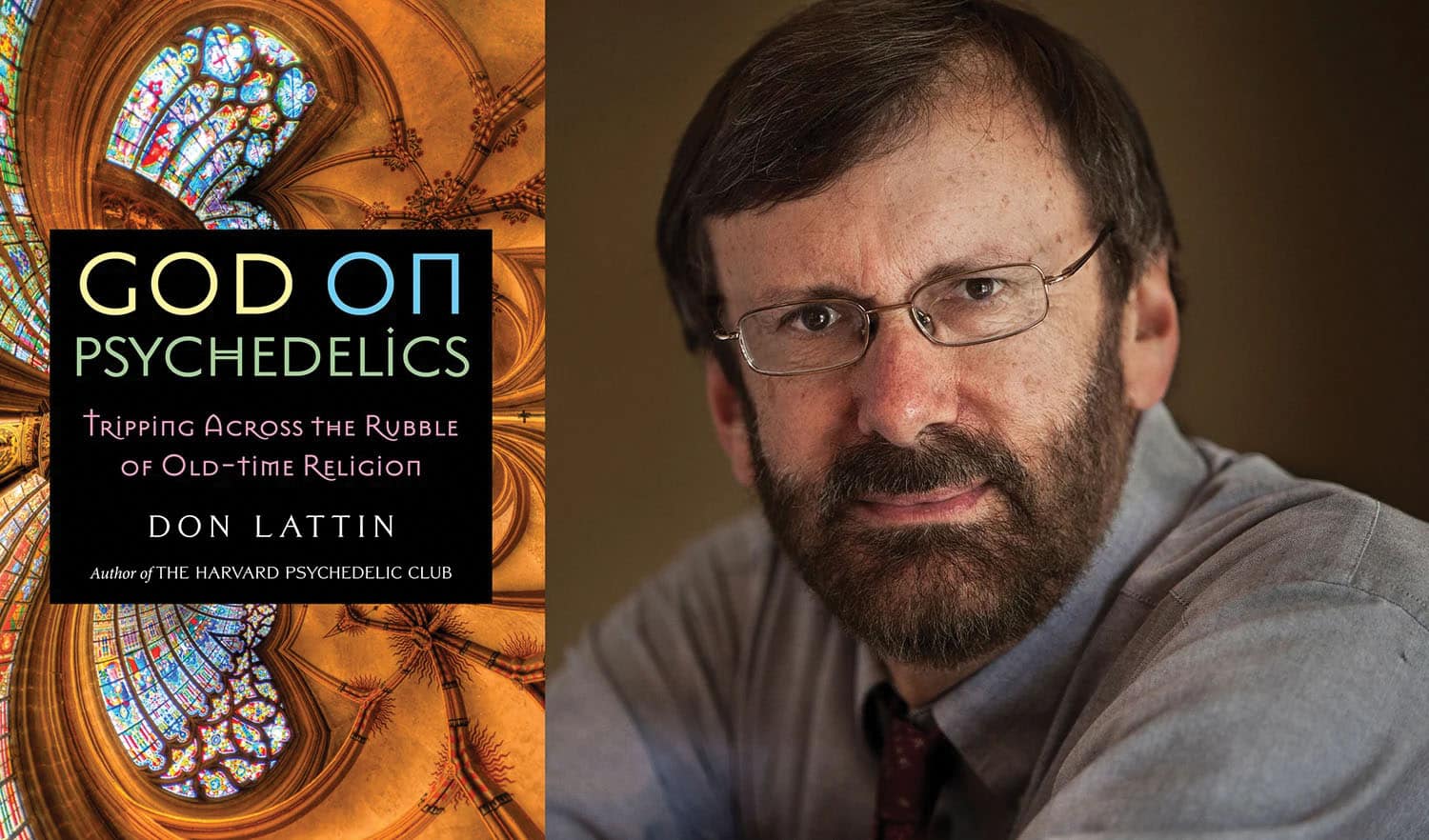

“God on Psychedelics: Tripping Across the Rubble of Old-time Religion” is Lattin’s latest book, and as the title indicates, it merges the two subjects he’s explored and written about for more than 40 years: religion and entheogens — a word which means ‘contacting the divine within’ and is now often used in place of ‘psychedelic’, which means ‘mind manifesting’ and has too many “groovy” ‘60s connotations.

One of the threads in “God on Psychedelics” is Lattin’s deep dive into the growing number of groups using entheogens as their sacrament. Oddly, some of these groups, as Lattin describes their gatherings, tend to mirror mainstream religions. Some call themselves a church — even when led by Jews; some request financial support from their congregation and whoever else wishes to support them; some chant and bond as a community; and some are subject to internal schism issues, just like Christians and Jews.

At the same time, these groups’ use of mind-altering plants as a sacrament, the lure that this will lead to a mystical experience, and their going into nature to carry out spiritual journeys, all that echoes much more primeval rites, whether Celtic, ancient Greek or Native American.

Another thread in “God on Psychedelics” is Lattin’s interviews with — and fascinating descriptions of — laity and clergy who have incorporated entheogens into their religious practice. Though much of the book is about those who come from Christian traditions, there is a chapter titled “On Being Psychedelic and Jewish,” in which Lattin profiles and quotes Jewish chaplains and rabbis, as well as Jewish scholars and lay ‘psychonauts’ — a newly-coined word that gives the act of ingesting entheogens the patina of lunar exploration.

Lattin writes that the increasing acceptance of entheogens among some religious folk, and the emergence of groups using it as their sacrament, indicate a deep-rooted desire for meaningful spiritual experiences, a desire that has traditionally not been satisfied by mainstream religions—as evidenced by the growing number of people who have left those religions and yet consider themselves, as is often heard, “spiritual but not religious.”

Lattin writes that the increasing acceptance of entheogens among some religious folk, and the emergence of groups using it as their sacrament, indicate a deep-rooted desire for meaningful spiritual experiences, a desire that has traditionally not been satisfied by mainstream religions.

“Mainline churches and synagogues have been in decline,” Lattin said in a Zoom interview, “those numbers have really fallen off the cliff in recent years … Both Christians and Jews I interviewed pointed out that churches and synagogues have done a terrible job of teaching people their own mystical traditions. There are reasons for that. Mysticism is dangerous for organized religion, whether or not triggered by psychedelics …

“When people have their own powerful personal experience of the divine, it may give them other ideas about what God is, or how they relate to God, or how they relate to the church or temple … So baby boomers — like me — came of age when a lot of people of my generation got into exploring other ways of being spiritual: Zen meditation, say, or maybe they hitched their wagon to an Indian guru, or got into Sufism or human potential movements.”

It’s no secret that a large number of Jews are among those who have explored other traditions, whether or not triggered by the use of entheogens. Lattin has often written about a Jew whose life epitomizes this journey: Richard Alpert—Ram Dass—one of the leading pioneers in popularizing the use of LSD, and one whose spiritual search in India influenced many others.

As Lattin points out, Ram Dass once famously said of himself, “I’m only Jewish on my parents’ side.” But Lattin, who interviewed Ram Dass many times, found that his attitude evolved during his life. “I interviewed him shortly before his [1997] stroke and we talked about his Jewish upbringing and his turning away from that …”

“In the end,” Lattin writes in “God on Psychedelics,” “Ram Dass never really embraced his Judaism … But he admitted that ‘had I been in a warm relationship with Judaism, it may well have been that I would have found… the maps that would have given me some structure to what I had experienced on psychedelics.’”

“When people have these powerful psychedelic experiences that radically change their sense of self or feel a divine presence in a whole new way,” Lattin said, “in some cases they look for road maps in their own tradition.”

One such person that Lattin interviewed for “God on Psychedelics” is Sam Shonkoff, professor of Jewish Studies at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Shonkoff told Lattin that “a major question … is how to tap into the creative forces of psychoactive plants and fungi without losing sight of the distinct gravity of ancestral Jewish sources.”

Another is Zac Kamenetz, a Berkeley-based rabbi who founded Shefa, an international movement trying to integrate the use of entheogens and Jewish spiritual traditions. Shefa holds bimonthly “integration circles,” Lattin writes, “where Jews from around the world share and process their psychedelic experiences in a culturally and religiously sensitive setting.” Lattin writes that Kamenetz told him that Shefa’s aim is to “bridge our [Jewish] religious traditions and psychedelic states to mutually inform, enrich and reenchant spiritual life …”

In “God on Psychedelics” Lattin writes about other Jews who have used, and are using, entheogens to explore Judaism’s more mystical aspects. There’s an interview with Boston-based rabbi Art Green, who among other accomplishments, founded the Havurah movement. Green told Lattin that his past entheogenic experiences enriched his practice of Judaism.

At the same time, Lattin writes that some scientists and researchers feel that entheogens should be used mostly in a medical/therapeutic setting. One such person is New Mexico-based medical doctor and psychiatrist Rick Strassman, also Jewish, who has objected to the “loose use of ‘mystical’” and has warned that established religions are going to push back at the idea that people can reach mystical consciousness by use of a psychedelic drug.

In spite of some scientists’ misgivings, Lattin feels that entheogen use in a religious setting is the leading edge of the spiritual-but-not-religious movement. “A lot of this is underground,” he said, “but there are literally hundreds, maybe thousands of small groups, sometimes not so small … People are finding ways to get together and explore these realms on their own. It’s definitely growing, and it’ll be interesting to see how it affects organized religion.”

Roberto Loiederman has written more than 100 articles for The Jewish Journal. He is co-author of “The Eagle Mutiny,” a nonfiction account of the only mutiny on an American ship in modern times.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.