“The Death of Democracy” is the title of Benjamin Carter Hett’s account of Weimar Germany, a time and place to which America today has been frequently compared. Like the second decade of the third millennium, the 1920s and early ’30s inaugurated a “shocking new world,” and democracy failed not only in Germany but elsewhere in Europe.

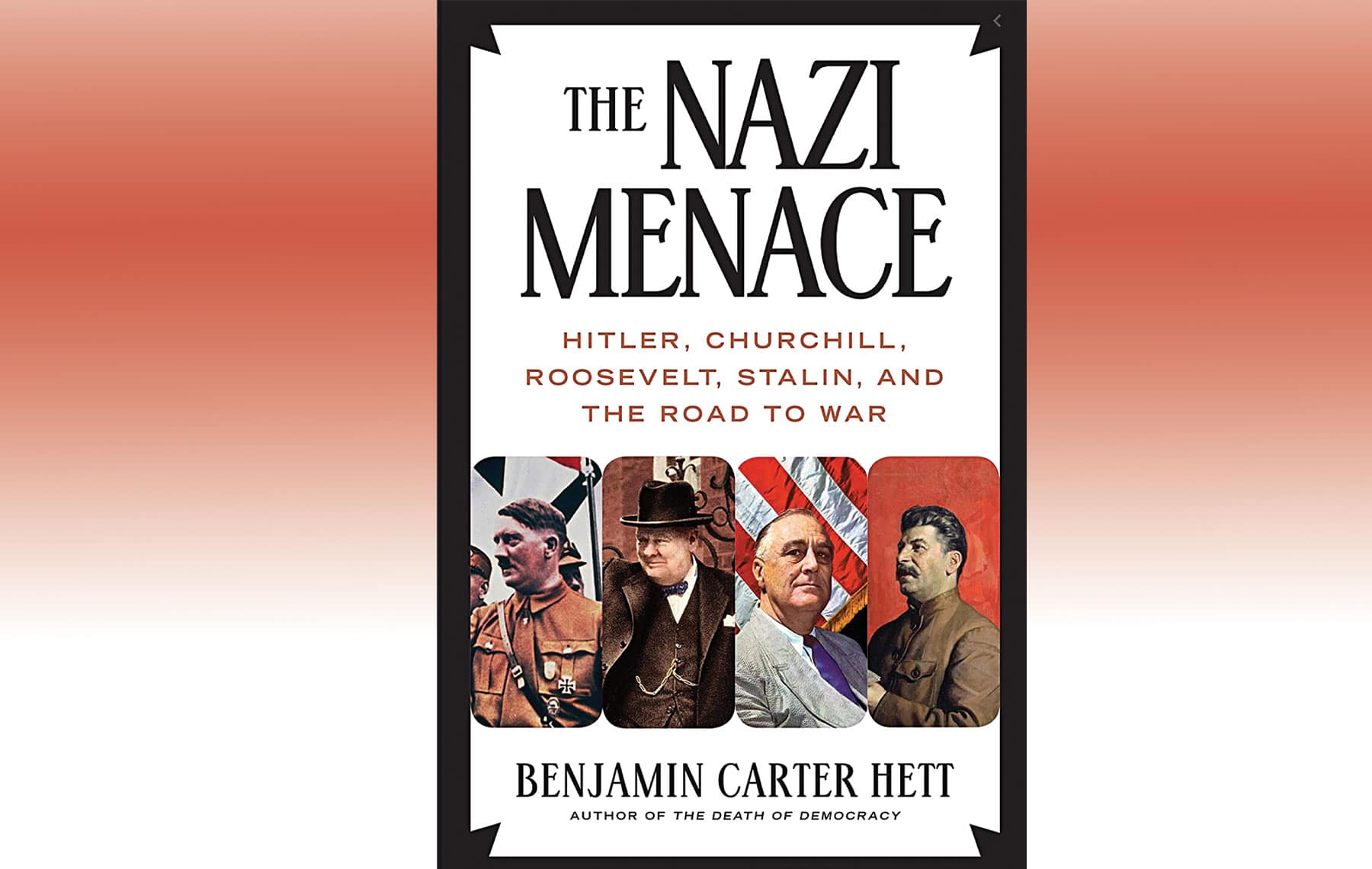

Now Hett shows exactly what happened next in his new book, “The Nazi Menace: Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin, and the Road to War” (Henry Holt & Co.), a lucid, vigorous and highly readable account of one of the great turning points of history. The cast of characters and the crucial events may be familiar to many (if not all) readers, but Hett usefully observes that “[w]e often fail to realize how contingent and unpredictable these developments were.” That turns out to be good news. By studying history, perhaps we are not condemned to repeat it.

Hett is a professor of history at Hunter College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. He holds both a doctorate in history from Harvard University and a law degree from the University of Toronto. As evidenced in his previous books, including “Burning the Reichstag,” “Crossing Hitler” and “Death in the Tiergarten,” he is adept at extracting the colorful and telling details from the historical record and weaving them into a vast tapestry.

Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, he points out, “started the 1930s a long way from where they ended.” Notoriously, the Western democracies worked harder to appease Hitler than to oppose him until he went to war against them. When Hitler, a private in World War I, first met with “his” generals in 1933, he finds himself in the company of “powerful and accomplished senior commanders who need not, and do not, feel in any way inferior to the new arrival.” Perhaps, the author suggests, “they don’t think this chancellor will last long enough for his ideas to matter much — after all, he is the fourteenth person to hold this office since 1919.”

The traditional centers of power in Germany, including the army, the bureaucracy and the corporations, tended to underestimate the chancellor who quickly reinvented himself as the Fuehrer. He made decisions impulsively and was convinced that he knew more than the generals. “For him, desks were mere pieces of decoration,” one of his subordinates recalled, and he “disliked reading files.” Yet those who might have opposed him were cowed by him. Hitler demanded — and received — a solemn oath of personal loyalty from even the most distinguished generals.

Hitler represented an existential threat the democracies of the world. “Was the world to be organized along liberal internationalist lines, with democratic systems everywhere, free trade, and rights for all, anchored in law?” writes Hett. “Or was the international system to be one of race and nation, with dominant groups owing nothing to minorities and closing off their economic space to the outer world as much as possible?” Yet the democracies, too, refused to stand up to Nazi Germany and its allies. When Hitler put his new military technology in service of fascist rebels in Spain, for example, The Times of London editorialized against intervention: “It may be that the system of parliamentary Government which suits Great Britain suits few other countries besides.”

Roosevelt understood the threat to Western civilization that Hitler represented, but he “seemed to float helplessly on the floodtide of isolationism,” as one of his biographers puts it. Then, as now, “the fight between those favoring international engagement and those preferring isolation was extraordinarily bitter,” as Hett points out. Under these political pressures, Roosevelt felt compelled to sign a Neutrality Act even as Germany and Japan were demonstrating their willingness to use the force of arms far beyond their own borders. But he warned that isolationism was not effective against an aggressive enemy.

“It seems to be unfortunately true that the epidemic of world lawlessness is spreading,” Roosevelt declared. “And mark this well: When an epidemic of physical disease starts to spread, the community approves and joins in a quarantine of the patients in order to protect the health of the community against the spread of disease.” But, FDR insisted, “we cannot have complete protection in a world of disorder in which confidence and security have broken down.”

Benjamin Carter Hett clearly wants us to compare our own plight to the circumstances that allowed authoritarians to come to power and then go to war.

“The Nazi Menace” is about far more than the tensions between democracy and fascism that eventually exploded into war. Hett shows us the inner workings of totalitarianism as it was practiced by Stalin with the same color and detail. And he explains how the Western democracies and the Soviet Union viewed each other with such profound distrust that a united front against fascism was far beyond reach. Neville Chamberlin, the British prime minister, “disliked the Soviet Union, its ideology, and its leaders at least as much as he disliked Nazi Germany.” When France and England consented to Hitler’s dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, Stalin concluded that “[h]e, too, must pick a side: with the democracies or with Germany.” Only days after German and the Soviet Union entered into a nonaggression pact, Hitler invaded Poland and World War II began.

Only then, of course, were Roosevelt and Churchill able to lead their countries into open conflict with fascism. But Hett’s premise throughout “The Nazi Menace” is that “there was nothing inevitable” about how it all turned out. “[W]ith different leaders, or with chancy political, technological, or military events going a different way,” Hett insists, the Allied victory over totalitarianism “might not have come at all.”

Hett clearly wants us to compare our own plight to the circumstances that allowed authoritarians to come to power and then go to war. “How should democracies respond to a security threat posed by a vicious regime?” he asks. “For what goals should a democracy go to war, and how should it fight? What do you do when your own democratically elected politicians serve as mouthpieces for the propaganda of a hostile foreign state?”

That’s exactly why “The Nazi Menace” is such an important and timely book. By looking back nearly a century, we find ourselves in a place that looks very much like the here and now.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.