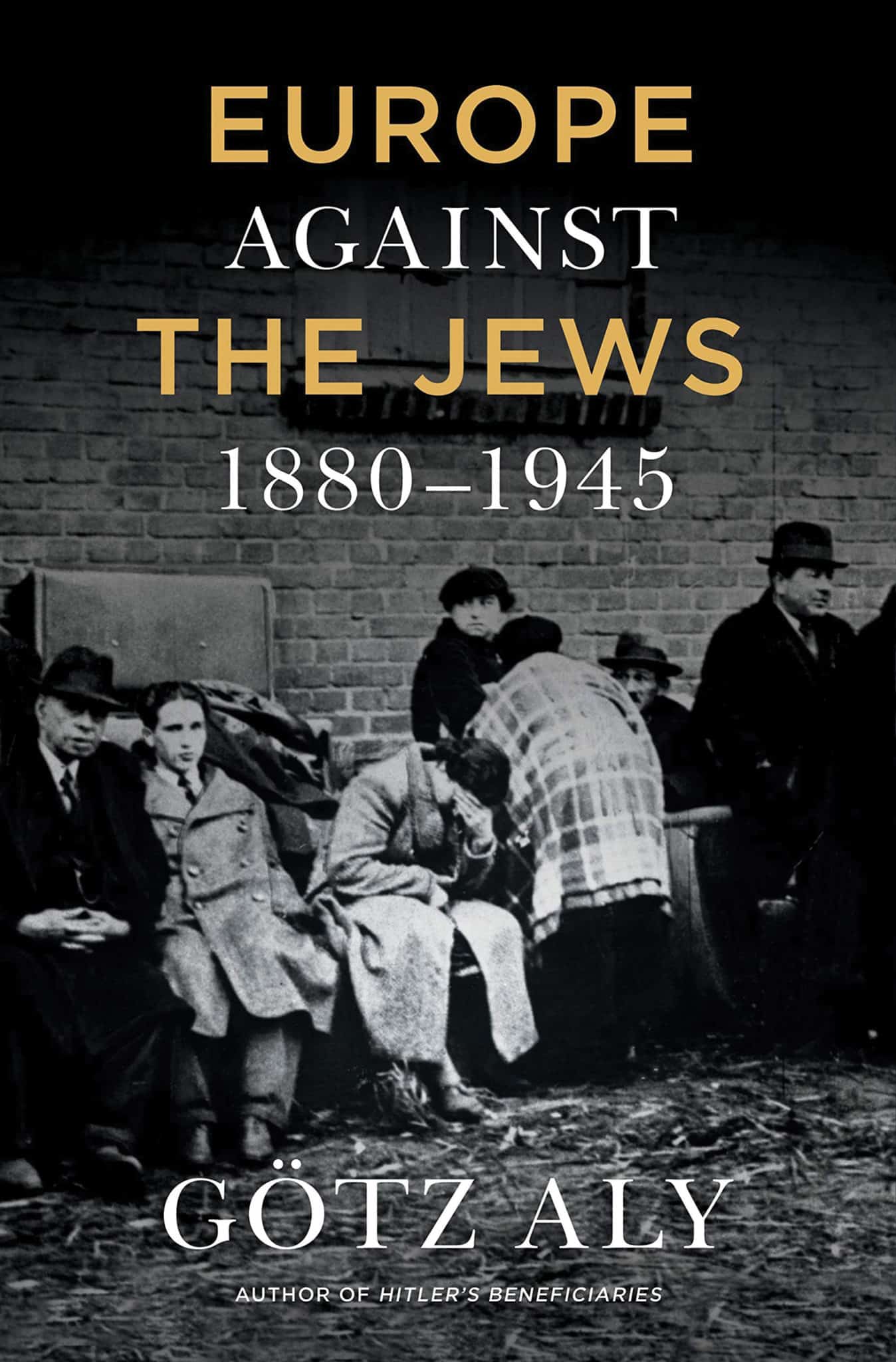

The chain of events that led to Kristallnacht began in Warsaw during the summer of 1938, as we are shown in the opening pages of “Europe Against the Jews, 1880-1945” by Götz Aly, translated by Jefferson Chase (Henry Holt & Co. /Metropolitan Books).

The Polish government issued an order that revoked the Polish citizenship of Jews who had been living in Nazi Germany for more than five years. “In response, at the end of October, German police arrested 17,000 Polish Jews, brought them to the Polish border, and forced them across,” Aly explains. He leaves out the tragic story of Herschel Grynszpan, whose parents were among the deported Jews and who assassinated a German diplomat in Paris as an act of protest against their maltreatment, thus providing Hitler with a pretext for the excesses of Kristallnacht. But he marks Kristallnacht as the turning point that put Germany on the path to the Holocaust.

Aly concedes the Germans alone were responsible for conceiving of the Holocaust, building the infrastructure of mass murder, and putting the machinery into operation, but he also insists “the genocide could not have been carried out solely by those who initiated it.” Indeed, he shows us the culpability of “administrators, police, state officials and thousands of non-German helpers who all played a role in the atrocities.” The point of his book is to spread the blame: “There is no way we can comprehend the pace and extent of the Holocaust if we restrict our focus to the German centers of command.”

Aly, a leading German historian of the Holocaust, is the recipient of the National Jewish Book Award as well as Germany’s prestigious Heinrich Mann Prize. His 2011 book, “Why the Germans? Why the Jews?: Envy, Race Hatred and the Prehistory of the Holocaust,” was reviewed in the Jewish Journal, and his new book can be seen as a kind of sequel, if only because Aly widens the lens to take in the persecution of the Jewish people by people and governments outside of Germany.

As I am sure he knew in advance, Aly’s book will be deeply off-putting to readers across Europe. He offers a catalog of the anti-Semitic ideas, policies and actions that are found in European history outside of Germany and before Hitler’s ascent to power. At the turn of the 20th century, Lithuanian anti-Semites warned that “Jews would turn Lithuania into the ‘Polish province of New Palestine.’ ” During the two years following the end of World War I, more than 1,500 pogroms took place in Ukraine. “Hitler cited France as an example of how he wanted to impose ethnic categories,” Aly writes, “if necessary with brute force.” The Hungarian fascist party known as Arrow Cross, “while related to the National Socialists was more radical”; its members “became reliable pillars in the new populist Communist regime after 1945,” a fact that explains the “stubborn refusal after the Second World War to talk about the Holocaust.” Croatia did not merely turn over its Jewish citizens to the Germans for deportation, but carried out its own program of mass murder.

Significantly, Aly finds only “two notable exceptions to the voluntary participation in the Holocaust” among the allied and occupied countries of Europe. One is Denmark, whose entire Jewish population was saved, and the other is Belgium, whose officials “refused to become complicit” and forced the Germans to do their own dirty work. When called upon to manufacture and distribute Star of David patches, the mayor of Brussels bravely declared, “Many Jews are Belgian citizens, and moreover we cannot commit ourselves to enforcing an edict that so obviously runs contrary to the dignity of human beings, whoever they may be.” The SS general who served as German military administrator was forced to send a sheepish message to Himmler: “Appreciation for the Jewish question not very widespread here” was the message the head of the German military administration sent to Himmler.

Even the United States attracts his attention, and he pointedly invites us to ponder the state of mind of Americans, both Jewish and non-Jewish, when he confronts us with the following uncomfortable fact: “In August 1920, the New York Times quoted the publisher of the Jewish Daily News, Leon Kamaiky, describing the situation and dreams of Polish Jews as follows: ‘If there were in existence a ship that could hold 3,000,000 human beings, the 3,000,000 Jews of Poland would board it and escape to America.’ ” Such fears contributed to the decision of the U.S. government to adopt a closed-door immigration policy that reduced the number of Jewish arrivals from nearly one million between 1901 and 1910 to only 18,000 from 1931 to 1935.

Hitler did not fail to notice that the western democracies were quick to criticize his anti-Semitic policies but slow to open their doors to Jewish refugees. Nor did Hitler’s future ally, Romania, one of whose leaders issued a dire warning in an interview with a Nazi party newspaper: “We have to force the Western democracies to choose between opening up new territories for Jewish immigration or accepting a violent solution to the conflict.” Among the members of the British Commonwealth, as it happened, only Australia offered to accept Jewish refugees, but limited its hospitality to an annual quota of 500 Jewish souls.

Aly repeatedly assures us he seeks only to reveal the origins and workings of the Holocaust in their entirety and not to diminish the German responsibility for its crimes against humanity. But he insists that some blame attaches to “the countries they occupied or dominated,” where anti-Semitism had existed long before Adolf Hitler found a way to recruit his willing foreign collaborators.

Jonathan Kirsch, book editor of the Journal, is the author of “The Short, Strange Life of Herschel Grynszpan: A Boy Avenger, a Nazi Diplomat and a Murder in Paris.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.