After Steven Spielberg released his epic film “Schindler’s List,” Holocaust survivors would approach the director and tell him, “That’s a great movie, but let me tell you my story.”

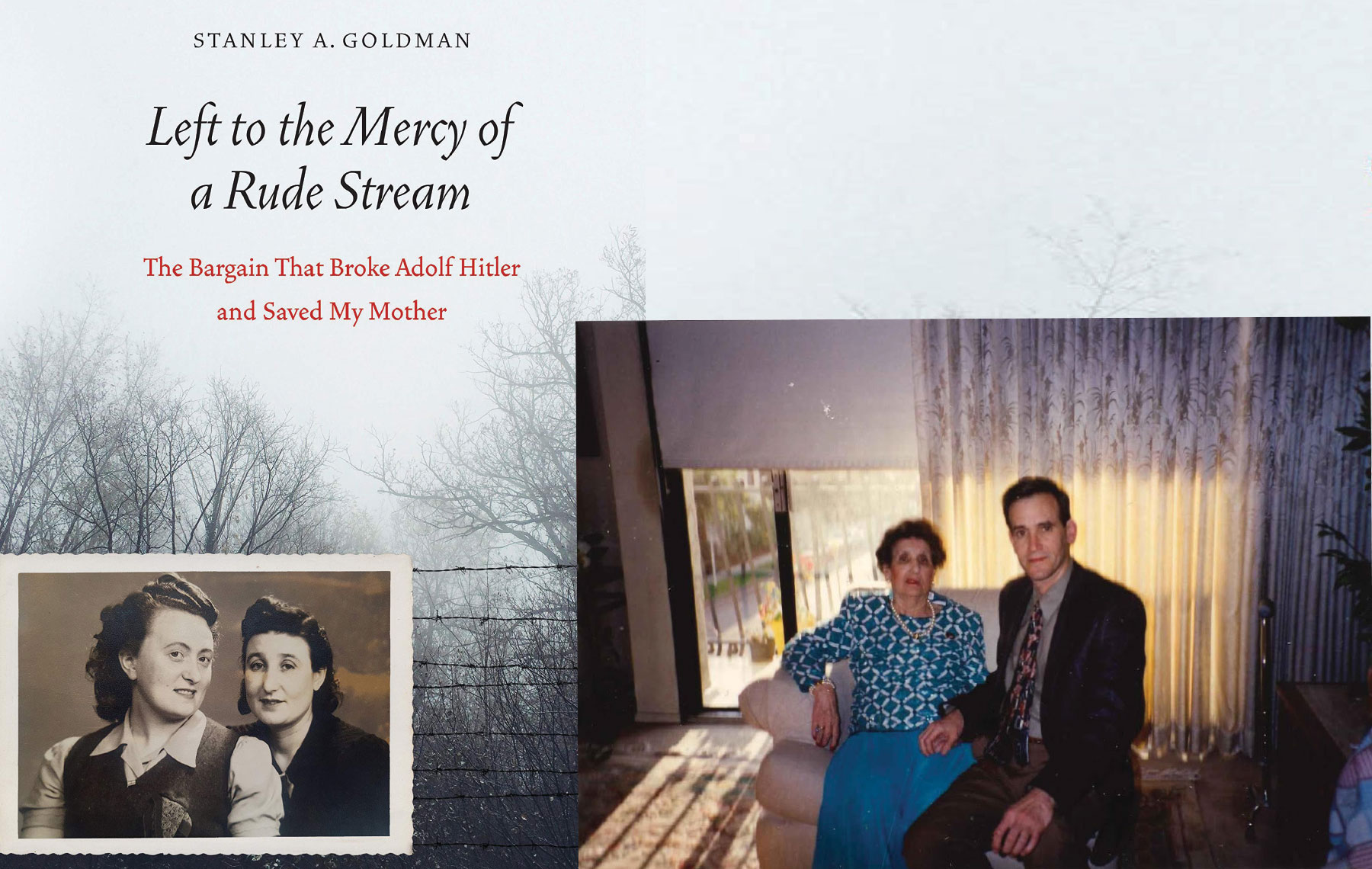

That anecdote came to mind when reading the new book by Stanley A. Goldman, “Left to the Mercy of a Rude Stream: The Bargain That Broke Adolf Hitler and Saved My Mother.”

Goldman, a professor at Loyola Law School who founded its Center for the Study of Law and Genocide, deftly mixes his personal experiences growing up the son of a survivor and the events surrounding the crash of Hitler’s 1,000-year Reich.

His mother, Malka, grew up in the town of Brzeziny, Poland. She was the ninth of 10 children and married when she was 17.

After the Nazis invaded Poland, her two children, ages 7 and 12, were taken from her, transferred to the Chelmo death camp and asphyxiated in airtight trucks doubling as gas chambers.

After the war, Malka emigrated, settled in Los Angeles and remarried, but she continued to battle traumas of the war years. One symptom was that she needed to know where her son, Stanley, was at any minute of the day or night.

“Because a reason for the unforeseeable horror that had taken her first two children was never given, she could never be convinced that it could not happen again,” Goldman recalls. “To her, chaos and tragedy were forever lurking. Even after I had grown into middle age, if she did not know where I was every night, she could be thrown into a panic. I would be born to a generation of loss, and it is not that extraordinary that pathological overprotectiveness would come to dominate our relationship.”

Goldman, who has enjoyed a career as a television and radio news correspondent and legal editor, writes with surprising frankness about how, again and again, promising romantic encounters with young women were interrupted and then terminated by his mother’s constant phone calls.

“Because a reason for the unforeseeable horror that had taken her first two children was never given, she could never be convinced that it could not happen again.”

— Stanley Goldman

As a result, he noted in an interview, he has never married. Although his mother is long gone, he is now in his late 60s and expects he is highly unlikely to change his ways.

In the book, Goldman says his mother’s wartime traumas also had an impact on his religious views as a youth. “As for religion” he writes, “if one sentence were needed to summarize how my parents raised me, it would have to be this: It was not that after the Holocaust we no longer believed in God, it was just that we were not prepared to talk to him until he apologized.”

The book’s second storyline is summarized in the subtitle, “The Bargain That Broke Adolf Hitler and Saved My Mother,” which sheds some light on the last days preceding Hitler’s suicide in his Berlin bunker.

In the spring of 1945, when it became obvious that Nazi Germany was losing the war and was caught in a pincer movement between the advancing Soviets and British and American forces, Hitler’s minions looked for ways to save their own skins. One of them was the head of the SS and Gestapo secret police forces, Heinrich Himmler, whose plump, bespectacled face and receding chin masked the heart of a mass murderer and fanatical anti-Semite.

Among Himmler’s showpieces was the women’s concentration camp at Ravensbruck. In lengthy talks with Count Folke Bernadotte of the Swedish Red Cross, and Norbert Masur, a German-born Jew with Swedish citizenship, Himmler deluded himself into thinking that if he released some 1,000 female Jewish inmates, he would escape prosecution as a war criminal.

Among the 1,000 was Malka, who was evacuated to Sweden and remained there for 18 months before leaving for the United States.

There is little doubt that when Hitler — holed up in his Berlin bunker within the sound of Soviet artillery — got word that Himmler was negotiating with the enemy, it hit him hard. Himmler was assumed to be the most faithful of Hitler’s followers, known to the Nazi top brass as “Der Anständige” or “The Decent One,” who would never desert Hitler.

Nevertheless, it is probably an exaggeration to suggest that Himmler’s defection “broke” Hitler and led to his subsequent suicide.

Noted Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum of American Jewish University, who praised Goldman’s book as “a powerful work,” has a somewhat more nuanced view of Hitler’s self-inflicted end.

“In his final testament, Hitler expelled Himmler from the Nazi party,” Berenbaum said, “but what broke him was the invasion of Germany from both east and west, which signaled the collapse of his entire world.”

The Journal asked Goldman whether, based on his research and family

experience, he thought mankind might ever face another Holocaust. His answer may give little comfort to “Never Again” optimists.

“The Holocaust was committed by one of the most sophisticated and advanced countries in the world. … It would seem, pessimistically, that as a species we have not been cured of the desire to destroy each other,” Goldman said.

Maybe 100 years from now, people will change, he added, but “there seems to be something in our DNA that keeps us killing each other.”

Although it may require a genetic change for humans to act in a humane way, Goldman said, “we cannot just throw up our hands.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.