A family of my close acquaintance still uses the Maxwell House Haggadah at every seder. It’s a deeply familiar haggadah that originated as an effort by the coffee company to attract Jewish consumers. To address the concerns of Ashkenazi Jews whose Passover kashrut prohibits the consumption of beans, a rabbi was recruited to certify that the coffee bean is actually a berry and not a legume. But the Maxwell House Haggadah quickly earned an enduring place in Jewish-American culture.

“The iconic blue cover and dual-column Hebrew and English translations have arguably become almost as emblematic of the holiday as the seder plate and Elijah’s Cup among Jews of the Diaspora,” Anne Cohen wrote in the Forward. “It has appeared in the suitcases of Soviet immigrants bound for Israel, been carried onto every battlefield the U.S. military has fought on since 1933, and been the guest of honor at the Obamas’ White House seder.”

By contrast, the haggadah that I use at home is my own effort at samizdat (dissident activity). Thanks to the internet, my haggadah includes portions of the traditional liturgy but also “Go Down, Moses,” an African-American spiritual; a meditation on the victims of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda; and a heart-shaking piece by former Jewish Journal contributor Yehuda Lev on a Passover that he attended while smuggling Holocaust survivors to Palestine in 1947.

So the haggadah remains a genre of Jewish art and literature rather than a sacred text. With Passover upon us, here’s a selection of haggadot — new, recent and classic — that reflect the richness and diversity of our tradition.

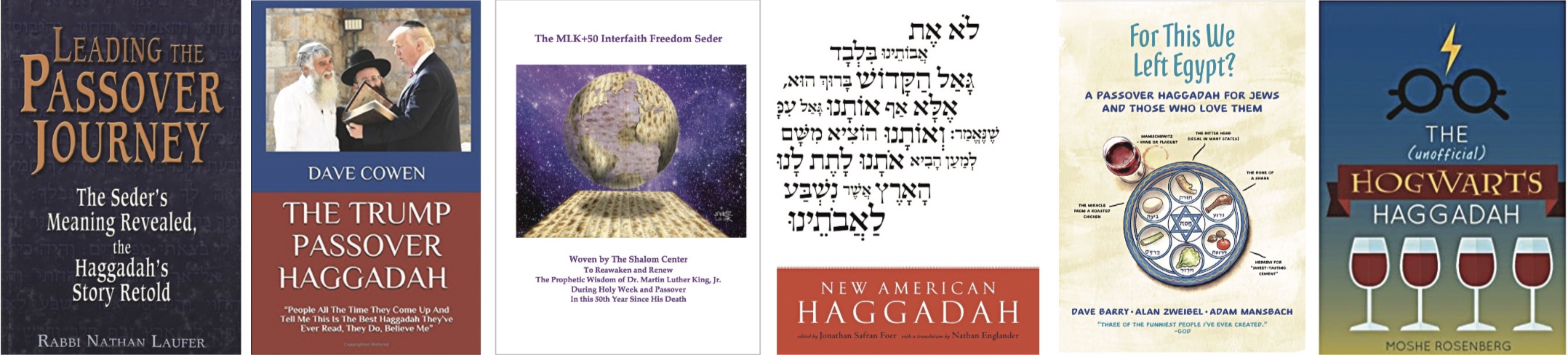

“Leading the Passover Journey: The Seder’s Meaning Revealed, the Haggadah’s Story Retold” by Rabbi Nathan Laufer (Jewish Lights) is a unique resource for anyone who is honored with the task of conducting a seder. Laufer makes the point that the haggadah is not just a script to be read aloud. Rather, the seder is an opportunity for contemplation, debate and reminiscence. “Each year, as our family read the Haggadah,” the author explains, “we inevitably segued into my family’s personal stories of survival and liberation from the Nazi concentration camps.” The cup set aside for Elijah, he says, was the only family heirloom that was recovered after World War II and now serves as a “cup of survival, hope and redemption.” At the same time, Laufer expands on and explains the subtext and symbolism of the traditional haggadah, thus addressing the fact that the haggadah asks far more questions than it answers. That’s why Laufer’s commentary is a good book to read in advance of Passover, but it’s even more useful at the seder table itself.

The newest haggadah is actually a book of political humor in disguise, and the joke starts in its title, “The Trump Passover Haggadah: People All The Time They Come Up And Tell Me This Is The Best Haggadah They’ve Ever Read, They Do, Believe Me” by New Yorker contributor Dave Cowan (Amazon). “I don’t know if Haggadahs were once great, and they started not being great at some point,” Trump is made to say. “Think of Trump’s Haggadah as a big play, and divide up the speaking parts amongst your guests, and you’ll re-live the greatness of Trump’s Seder.” Everyone from Melania Trump to Bernie Sanders has something to say. This book is certain to liven up any seder — if it does not result in a brawl among the Trumpers and the Never-Trumpers at your table.

Another new Haggadah with a political agenda is timed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. “The MLK+50 Interfaith Freedom Seder” is a publication of The Shalom Center and is downloadable without charge from the website theshalomcenter.org, although a donation of $18 is suggested. It is authored by Rabbi Arthur Waskow, who introduced the first “Freedom Seder” in the 1960s and now directs The Shalom Center, and is “woven” from three strands — the traditions of Passover, the “echoes of Passover in the Christian Holy Week” and the writings of King. The goal is to connect the ancient story of resistance to Pharoah and the continuing story of resistance to racism, materialism, militarism and sexism in America right now.” Significantly, and not surprisingly, this updated version of the “Freedom Seder” ends not with “Next Year in Jerusalem” but with “We Shall Overcome.”

Here’s a selection of haggadot — new, recent and classic — that reflect the richness and diversity of our tradition.

One sign that the haggadah remains a vigorous literary genre is the fact that an assortment of Jewish authors have tried their hands at haggadot of their own over the past few years. “New American Haggadah,” edited by Jonathan Safran Foer and translations from Hebrew by Nathan Englander (Little Brown) — both of them authentic literary luminaries — is both a full-featured haggadah and, at the same time, a fresh and elevating experience. “We are not merely telling a story here,” they explain. “We are being called to a radical act of empathy.” By contrast, Dave Barry (“He is not Jewish, although many of his friends are”), Alan Zweibel and Adam Mansbach offer a parody in “For This We Left Egypt? A Passover Haggadah for Jews and Those Who Love Them” (Flatiron Books). “We look forward to celebrating Passover for many years to come,” goes the blessing over the Fourth Cup, “until we have to gum the matzoh for fifteen minutes before we can swallow it, which we will do because it reminds us of something, although by that point we will probably not remember what.”

Perhaps the most counter-intuitive haggadah is “The (unofficial) Hogwarts Haggadah” by Rabbi Moshe Rosenberg (BSD), which makes highly inventive use of the Harry Potter saga. For Jewish readers who recall the stern words of Deuteronomy (“There shall not be found among you … a sorcerer, or a charmer, or a medium, or a wizard…”), the conjuring up of the most famous graduate of the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry may be off-putting. Be assured, however, that the author is a pulpit rabbi with a lively imagination and a gift for catching and holding the interest of Harry Potter fans as he guides them safely to the traditional Jewish values and observances of Passover.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.