In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as part of a scattershot back-to-the-land movement, hundreds of communes cropped up throughout the U.S. Young men and women who had taken the measure of the country — war, recession, consumerism, middle-class values — and found it wanting, settled most of the communes. Each was different, but they all shared the dream of a rural paradise where they could dig, plant and build a world of their own making.

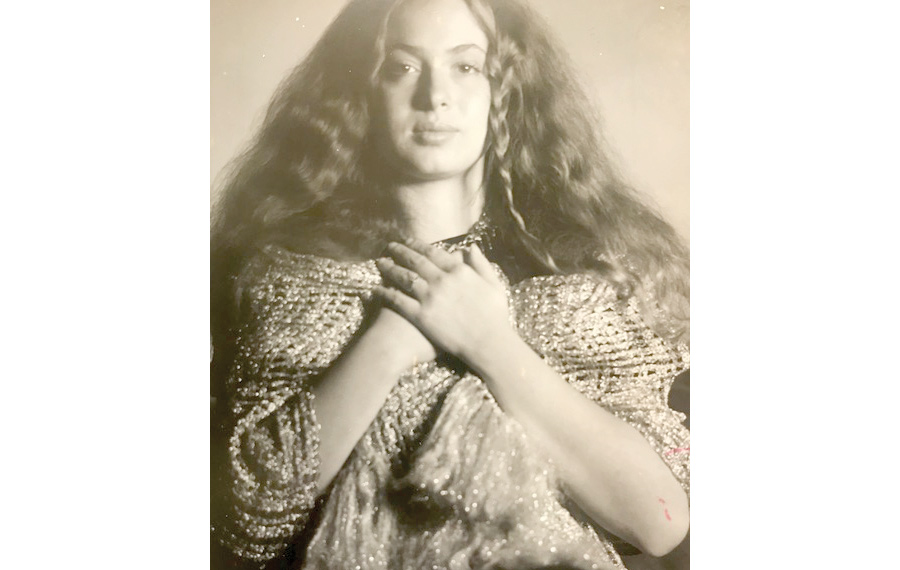

In a recently published memoir titled “Hippie Woman Wild,” Carol Schlanger describes — in hilarious and at times cringingly honest detail — the struggles, loves and joys of living in a commune in rural Oregon in the early 1970s. Her experiences in two locations — first on a piece of leased property then on land that Schlanger bought — involved roughly a dozen people doing their best to survive a hardscrabble life, doing whatever they had to, whether it was (illegally) growing marijuana on nearby government land or using a ruse to obtain food stamps.

On Aug. 11, Schlanger — an actor-writer who lives in L.A. and in Oregon — will perform an excerpt from her book at the Jewish Women’s Theatre (JWT) at the Braid in Santa Monica, and answer questions about her experiences.

Before being in a commune, Schlanger (who wrote that she was a “not-so-nice Jewish girl” back then), was a graduate student at Yale Drama School, where she met a “stoner cowboy” from Texas, Clint Helvey, who was at Yale’s architecture graduate school.

“Clint was much more hippie-ish than I was,” Schlanger said. “I was pretty straight. I had turned down marijuana my whole life, really focused on my work.” Schlanger told the Journal that Helvey introduced her to LSD and to the possibility of living a different kind of life.

After an irony-laced, rebellious interaction with the school’s dean contributed to her getting kicked out of Yale, Schlanger moved back to New York, her hometown, where she found acting work. Helvey joined her. “Clint didn’t like living in New York,” she said, “His friends were in Oregon, starting a commune, so he left and begged me to come with him. I didn’t want to go. My career was starting to take off. I knew I’d miss it. But I also missed him. … So I went.”

In Oregon, Schlanger found “an anarchist situation, a free-flowing place with no dogma, no leaders. The only rule was ‘You can’t tell anybody else what to do …’ ”

There was a core of people who stayed, others came and went. For Schlanger, the crisis came when the commune was “raided by a motorcycle gang. Since it was an open-door policy, [the bikers] were welcomed. … I didn’t like that, so I said, ‘That’s it, I want my own place. Clint and I will have a Tarzan and Jane life, it’ll be really gorgeous, there’ll be waterfalls, we’ll live as a man and woman should live.’ ”

With help from Schlanger’s family, Schlanger and Helvey bought a piece of land in a different part of Oregon. “It was very remote,” she said. “There was no electricity, no running water, no road that you could use except with a four-wheel drive. Nothing around for hundreds of acres.”

After moving to the land they’d bought, Helvey, to Schlanger’s dismay, invited the previous location’s core group to join them. “I was furious that Clint invited them,” Schlanger said. “But without them, I never would have survived at all. … When you’re in remote circumstances, you’re all in the same foxhole.”

“I didn’t have a lot of skills. I was kind of a crappy hippie. At first, I didn’t know how to chop wood or how to bake. I couldn’t sew. I got lost in the woods.”

— Carol Schlanger

Growing up in a fairly affluent Jewish home in New York as an only child, Schlanger said, “I’d never done my own laundry, and all of a sudden I was doing laundry for 12 people. … I can’t say I loved that part of it very much, but I loved the sharing.”

But it didn’t always feel like Eden.

“You miss things,” Schlanger said. “You miss hot water. Something that would take five minutes in the outside world would take you two days, so you had to have patience. … You had to chop down a tree just to cook beans. You stop taking things for granted. When I’d go away from the commune and be able to take a hot shower, that was like a miracle. I’d be in ecstasy.”

Schlanger said that for the most part, they learned to take care of their own medical needs, but when her first child, a son, was about to be born, Schlanger rejected giving birth in a remote area with no doctor and Helvey drove her to a hospital. She said she made that choice because communal living had “cracked open” her mind, “but not to the point of becoming scrambled.”

Food was always an issue. In the excerpt Schlanger performs at JWT, she goes to a government office to get food stamps. In the waiting area, there’s a woman with a baby and Schlanger makes a deal: If she can borrow the baby for the interview, she’ll give the woman some food stamps.

The woman agrees. With a baby she’s never seen before in her arms, Schlanger pretends to be “a slow-witted backwoods woman who’s got four kids and a blind husband who’s a goatherd.”

Success! Schlanger gets a life-saving stack of food stamps. When she gives the baby back to the mother, Schlanger peels off some food stamps for the woman, who’s not satisfied with her cut. As Schlanger hurries away, the woman yells out: “Jew!”

Schlanger shrugged off the slur. “Without those food stamps, we would have had to eat a lot of squirrel. … Look, I didn’t have a lot of skills. I was kind of a crappy hippie. At first, I didn’t know how to chop wood or how to bake. I couldn’t sew. I got lost in the woods. But by getting food stamps, I helped the others survive. And it was fun being an actress for a few minutes.”

After a couple of years, the commune dissolved, as most others did. Schlanger, Helvey and their toddler — named, you guessed it, Huckleberry — moved on to the next phase of their lives.

“I learned a lot there,” Schlanger said. “Most important lesson: How to read bear scat. If it’s fresh, there’s a bear nearby. Scat size tells you if the bear’s big or little. I may be the only woman on the Westside who can read bear scat. I’m proud of that!” Schlanger laughed heartily at her own joke.

As Schlanger’s friend actor Henry Winkler has written about her, “Carol can’t say a sentence — she can’t write a sentence — without making you laugh.” n

“Hippie Woman Wild” performance and author talk with Carol Schlanger is 10 a.m. Aug. 11 at the Braid, Jewish Women’s Theatre.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.