Going to high school at Marlborough School in Hancock Park, Charmaine Craig felt the weight of her unusual Southeast Asian heritage, coming from an ancient people called the Karens who resided in the jungle valleys of what was then called Burma.

Her mixed-race background — Karen, Jewish and white — meant other students often asked her what she was. When she answered that she was Karen, they corrected her, “You mean Korean.”

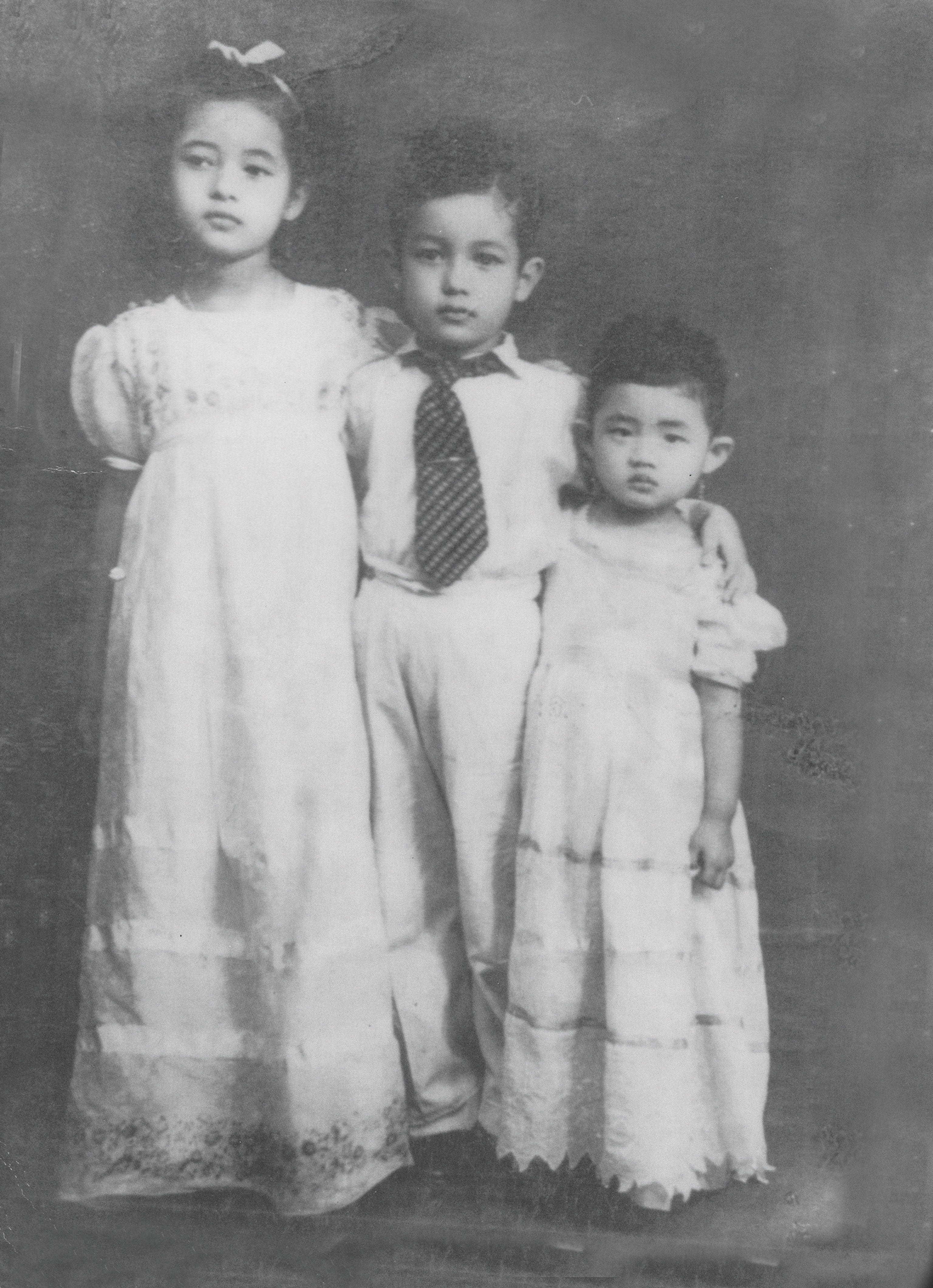

The question of belonging is as central a focus of her new book, “Miss Burma,” as it was during her childhood. The novel traces her mother’s upbringing in the country now known as Myanmar. Louisa Benson Craig was born in 1941 to a Jewish father and a Karen mother, and became a national beauty queen in 1956. Her beauty was exploited in the name of national unity, but she later fought back, becoming a rebel leader in the Karen revolutionary struggle.

READ MORE: ‘Miss Burma’ Is All Too Relevant to Myanmar’s Modern Violence

While Charmaine Craig was growing up in Santa Monica, her mother longed to return to her homeland in spite of the bounty put on her head by the government. She struggled with the scars of her past; as a kid, her daughter sometimes would find Louisa hiding under a table. Now the author has opened those wounds — her mother’s and her own — for the sake of examining Myanmar’s complicated and troubling ethnic history.

Craig, a professor of creative writing at UC Riverside, recently sat down for an interview in the backyard of her Craftsman home in West Adams.

Jewish Journal: The world’s attention has turned to Myanmar because of allegations of ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya minority. Did you intend this book to be timely or political when you started writing it?

Charmaine Craig: I absolutely intended it to be political, because I have known that a lot is going on in Burma the entire time I’ve been writing the book, which is 15 years. There have been waves of genocidal campaigns against different minority peoples in Burma, including the Rohingya, but also some other groups, that entire time.

So I was aware in the last seven years, five years of writing this book of what was going on with the Rohingya — by the way, a situation that goes all the way back at least to the ’30s — and aware of what was going on with the Shan, with the Kachin [other ethnic groups native to Myanmar]. It was important to me while writing the book to give historical context for how Burma ended up, how the mistakes that have been made repeatedly by the West have had historically and continue to have a part in the persecution of Burma’s minority groups.

READ AN EXCERPT: ‘Miss Burma’

JJ: Your grandfather was an English-speaking Jew from Rangoon. How do you relate to your Jewish heritage?

CC: I was in touch in Los Angeles with the Jewish side of my family, but they were sort of second and third and fourth cousins. There was a warm feeling there, a familial closeness, and yet I wasn’t really part of that community, either. I longed to participate, and I think my mother did, and I know my older daughter does. And so there was a generational feeling of being held at bay from the community and not included.

And yet I will say that my husband is very close, as am I, to the Jewish side of his family. So we participate in their rituals and so forth. My older daughter has been asking me if we can start going to synagogue, and it’s a conversation my husband and I have had from time to time.

JJ: In the book, you write about an encounter between your grandmother and the rabbi of Rangoon, where she’s discouraged from becoming a Jew. Was that scene in the book informed by your experience of being held at arm’s length from Judaism?

CC: A lot of the conversation that happens in the book came out of my experience of that, to an extent. But more so, it came out of my understanding of the minority peoples of Burma — not the Rohingya, but most of them — being told that they belong explicitly, and yet implicitly that they do not belong. “Here’s the way that you can be a vital and unoppressed member of our society: Assimilate utterly. Stop teaching your languages in your schools. Stop talking about self-determination.”

JJ: Do you ever consider the similarities of the Jewish and Karen experiences, in terms of perpetually homeless, exiled, of being made a stranger? Did that influence your writing at all?

CC: I’m sure it must have. I do want to note that even on the level of creation stories, the Karen faith is very Mosaic. There are startling similarities. I mean, their word for god is Y’wah.

JJ: Are Karens monotheists?

CC: They believe in spirits, so you could say they’re animists, but you could also sort of say they’re monotheists.

The feeling of exile that you mentioned, the feeling of always wandering, perpetually being rootless, perpetually feeling shunned from where you are — my mother in her blood, and in some sense even I felt that here. And so absolutely, to put it in your words, that sense of perpetual homelessness is part of my identity.