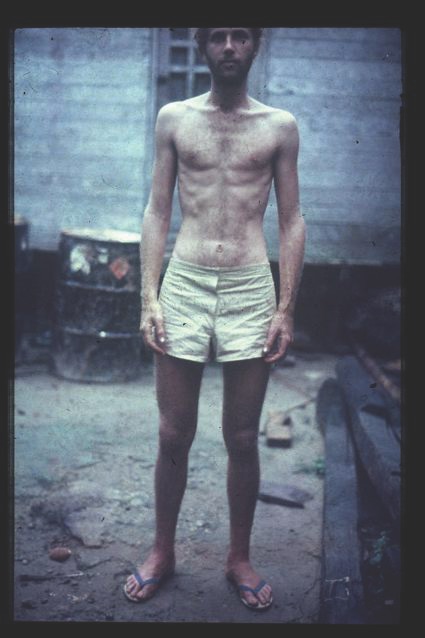

Actor Daniel Radcliffe portrays Yossi Ghinsberg in the film “Jungle.” Photo courtesy of Momentum Pictures.

Actor Daniel Radcliffe portrays Yossi Ghinsberg in the film “Jungle.” Photo courtesy of Momentum Pictures. One night during the 20 days Israeli backpacker Yossi Ghinsberg was lost in the Bolivian Amazon, he was wrapped tightly in his mosquito net when a swarm of army ants began tearing at his flesh.

“I pulled them off my eyelids, out of my ears, out of my hair, from my arms and legs,” Ghinsberg, 58, wrote of the experience. “My body was like a sieve, drops of blood seeping through every patch of bare skin.”

Ghinsberg’s memoir of the 1981 experience, “Jungle: A Harrowing True Story of Survival in the Amazon,” now is a film, “Jungle,” starring Daniel Radcliffe, which opens Oct. 20.

The ants were just one of the traumas Ghinsberg, then 22, endured in one of the most dangerous jungles on earth. He survived starvation, two near-deadly immersions in quicksand; dozens of leeches; a flood that carried him roughly through the forest; hurtling through a river canyon that constantly pulled him under the water; vicious fire ants; a fungus that left his feet bloody; oozing pus; and myriad jaguars.

On a mountain peak, a big cat once approached him, clearly interested in a meal. Drawing on a technique he had seen in a James Bond movie, Ghinsberg shot a flame through insect repellent spray to create a fireball aimed at the feline. The flames scorched his hands but also frightened off the cat.

On a mountain peak, a big cat once approached him, clearly interested in a meal.

“Yet almost every morning, I would see jaguar tracks just a couple of yards from my head,” Ghinsberg said in a telephone interview from his home in a subtropical rain forest two hours outside of Brisbane, Australia. “I had no gun, no machete. It’s a mystery, because jaguars in that area can and will attack.”

Ghinsberg grew up the son of Romanian immigrants. His father, he said, had a vendetta against God. He had survived the Holocaust in a German work camp in Siberia, and afterward “obsessively broke every Jewish law on purpose,” Ghinsberg said. “He would only eat pork, and on Yom Kippur, he would prepare a feast and eat it.”

But Ghinsberg also had a devout uncle, a rabbi and kabbalah scholar named Nissim, who unexpectedly called Ghinsberg to his home in Rehovot one day. The 83-year-old had something to give the young man before Ghinsberg started his compulsory service in the Israeli navy. The gift was a small book, a kabbalistic treatise, filled with symbols and prayers in Aramaic. “This was with me during the Holocaust and the hard times, and it protected me,” Nissim told Ghinsberg. “Promise me you’ll always keep it with you.”

When Ghinsberg returned home an hour later, he was shocked to discover his mother screaming — Uncle Nissim had just died of a heart attack.

Ghinsberg kept the book with him throughout his navy experience. He kept it in tow when he went off on the exotic backpacking trip Israelis famously embark on after their military service. “I went to South America with the idea that I would be an explorer, that I’d find lost tribes, become one of them, marry the chief’s daughter and find riches of gold,” he said.

In La Paz, Bolivia, Ghinsberg chanced to meet a guide who promised him that kind of adventure: Karl Ruchprecter, who presented himself as a maven of the jungle. Ghinsberg convinced two fellow backpackers, Marcus Stamm, a Swiss traveler, and American Kevin Gale, to join them. Looking back, “I was so naïve,” Ghinsberg said of choosing to trust Ruchprecter.

The journey started benignly enough — though Ruchprecter took his time shooting the wild animals he had promised the group. When they were ravenous, he killed a monkey, which was “very, very gamey” in taste,” Ghinsberg recalled. “But when you’re hungry to that level, you just need the energy to come in, and that’s why nothing is disgusting.” If necessary, he added, “I would have eaten human flesh.”

Then there were the tensions that began to divide the group. Stamm developed a painful foot fungus and was unable to keep up with the others. He also was a “saintly figure” who eschewed eating monkeys and chopping down trees to get at the fruit, Ghinsberg said. “His tragedy was that his compassion wasn’t appropriate for such circumstances.”

Moreover, Ruchprecter turned out to be a sociopath and a compulsive liar. At one point, he told Ghinsberg that the Israeli could not visit his uncle’s Bolivian ranch because the man was a fugitive Nazi war criminal who hated Jews. (Later Ghinsberg learned Ruchprecter had no such uncle.)

The group split up after a couple of weeks. Ruchprecter went off with Stamm to walk to a faraway town, and Gale and Ghinsberg decided to reach civilization by fording the treacherous Tuichi River. It was during that attempt that Ghinsberg was swept off the raft and over a waterfall, suffering a bloodied head along the way. From that point on, he was stranded alone in the jungle until Gale arrived with a boat to rescue him nearly three weeks later. Meanwhile, Ruchprecter and Stamm disappeared and were never seen again.

Along the way, Ghinsberg, who had not previously thought much about God, became a believer. “I found my faith during this experience, because many times there was nothing for me to do but scream, ‘God, please help me!’ ” he said. “Every time I found an egg to eat, or when I survived a storm in which trees were collapsing all around me, I felt that it was Providence. I don’t need to believe — I know.

After Ghinsberg was rescued, he read many of the Jewish books Uncle Nissim had left him and studied kabbalah at Tel Aviv University, as well as with scholars in Safed. He went on to explore Eastern religions and Native American shamanism, returning to Bolivia to help villages there develop ecotourism businesses. His 1985 memoir became a cult phenomenon in Israel.

Today, Ghinsberg lives in Australia with his third wife, Belinda, and their two young children (he also has a 32-year-old daughter from a previous marriage). He works as a technology consultant and a motivational speaker, drawing on his own experiences of survival in the jungle. He meditates regularly in addition to celebrating Shabbat and the Jewish holidays with his family.

The film’s producer, Dana Lustig, says Ghinsberg’s story offers inspiration for anyone struggling to overcome tribulations. “Who among us hasn’t had a heartbreak?” she said by way of example.

Ghinsberg agreed. “I hope this film will empower people,” he said, “and give them hope and perspective about battling their own traumas.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.