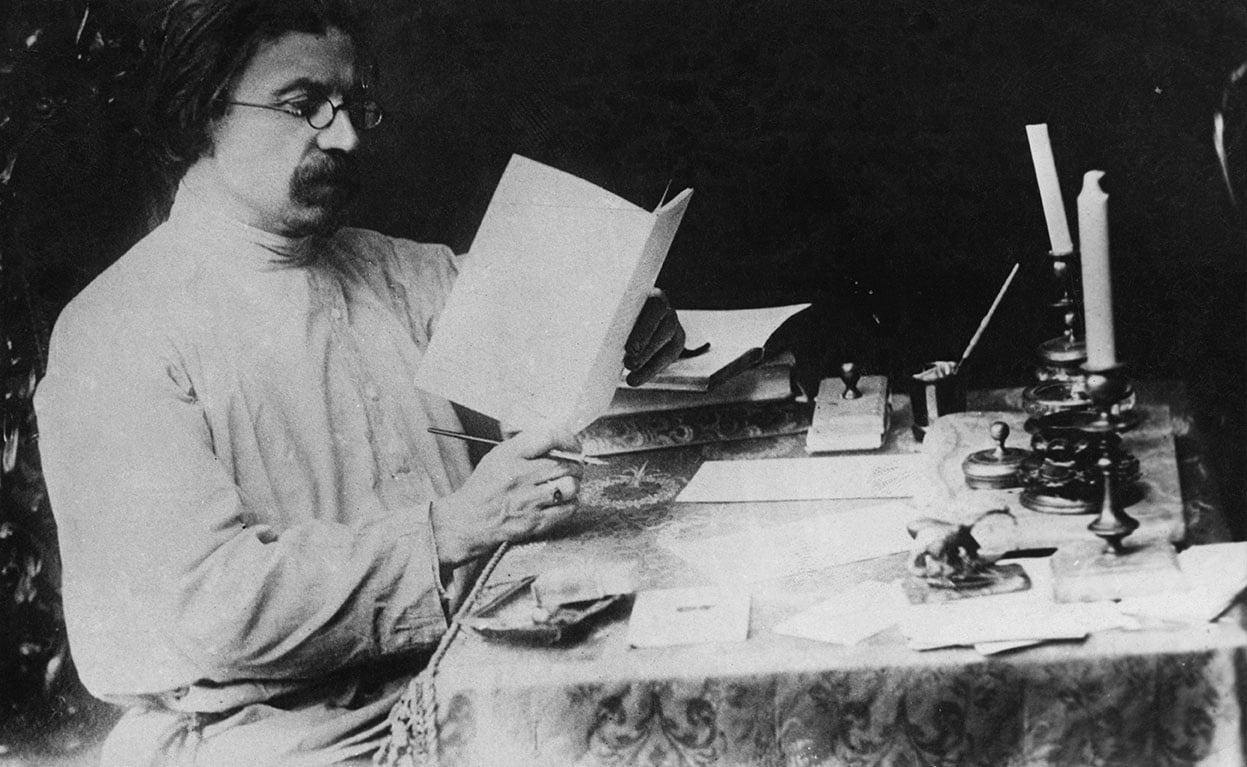

Ukrainian-born Jewish author and playwright Sholem Aleichem (1859 – 1916) working in his study, circa 1900. (Photo by FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Ukrainian-born Jewish author and playwright Sholem Aleichem (1859 – 1916) working in his study, circa 1900. (Photo by FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images) “Life is a dream for the wise, a play for the foolish, a comedy for the rich, a tragedy for the poor.”—Sholem Aleichem

Sholem Aleichem’s “Fiddler on the Roof” is a story of the Judaism of Eastern and Central Europe, and of the “shtetl,” the town or village granted and demarcated for the Jewish population in those areas. At the time in which the story is set (late-19th and early-20th centuries), the union of the vast territories of Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Moldova was known as the Pale of Settlement (“Chertá Osédlosti” in Yiddish). The Pale of Settlement was created by Tsarina Catherine the Great in 1791 in order to enclose in some way the Jews who were beginning to form a bourgeoisie, although in some cases they were also engaged in farming.

One of those places where the world of the shtetl and Yiddish language and culture flourished was in Ukraine, far removed from German enlightened Judaism and perfectly alien to the world of Ladino and Sepharad. There, a play about the daily life of a small Jewish merchant, part of the nascent local bourgeoisie, known as Tevye “the milkman,” was immortalized to this day.

Sholem Yakov Nokhuomovich Rabinovich, better known as Sholem Aleichem, was born in an old town in the Kiev Oblast. Pereiaslav, which had its name altered by the Soviets in 1943, was renamed Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi after Bohdan Khmelnitskyi, a Cossack ally of Alexander I’s Russia, the first “Hetman” (ruler in Poland, Ukraine and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) of the Cossack Hetmanate (Ukrainian-Cossack state). However, in 2019, the Ukrainian parliament reinstated the city’s original name, to disassociate it for obvious reasons from a Russian-edged past, though this fact is evidently still in dispute.

The city, which is known as a “living museum” because of its history and number of museums, was once home to a Jewish community, dating back to at least the 17th century, with a written record from 1620, in which the city’s residents complained to King Sigismund about the Jews’ commercial boom, given that they were limited, as in most cases, by restrictions on the use and development of the land. It is striking that the only evidence proving the existence of the Jewish community in Pereiaslav mentions an antisemitic event. But just as there was a considerable Jewish population throughout this area of Central and Eastern Europe, there was always a latent antisemitism among the very people among whom the Jews lived.

Under the pseudonym or nom de plume of Sholem Aleichem, Hebrew for “peace be with you,” Sholem Rabinovich was by no means oblivious to this reality, despite having been among the letters from a very young age and having been born into a bourgeois (though later impoverished) family and then having married his ward Olga (Hodel) Loev, daughter of one of the few Jewish landowners.

Aleichem wrote his first novel at the age of 15, a Jewish adaptation of Daniel Defoe’s most famous novel, “Robinson Crusoe.” Although he had idealized writing in Russian or Hebrew, he later turned to Yiddish after analyzing its better accessibility to the Jewish masses and of course realizing that his world was the shtetl. Aleichem’s stint in the world of journalism is no less irrelevant than his work, for from 1879 he became a local correspondent in Kiev for the renowned Hebrew newspaper “Ha-Tsefirah” (“The Epoch” in Hebrew), the first newspaper published in Hebrew in Poland, founded in Warsaw by Ḥayim Zelig Słonimski and published between 1862 and 1931. The main purpose of this weekly was to report news about Jews in the area and to provide general information, including articles on natural sciences and the latest inventions.

In turn, from 1880 to 1883 Aleichem served as crown rabbi in Lubny, a position in the Russian Empire that consisted of being an intermediary between his community and the imperial government. The court rabbi was responsible for civil duties such as the registration of births, marriages and divorces. The main requirement for this position was to be able to communicate in Russian without any problems. Also, the crown rabbis were considered agents of the state, not real rabbis, and were generally not educated and had no knowledge of Jewish law.

Although he was a Yiddish writer and not really connected with the Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment), he was not far removed from it either. In 1881 and 1882 his articles focusing on Jewish education appeared in Ha-Melits, the main medium for disseminating Haskalah. Aleichem was, of course, a “maskil,” a Hebrew and Yiddish scholar, an “enlightened one.”

Similarly, Aleichem’s official work was released in 1883, when he was 24 years old, with “Tsvey Shteyner” (“Two Stones”), his first Yiddish story, using the Sholem Aleichem nom de plume for the first time. In this first work he fictionalizes his romance with his future wife. The story ends with the suicide of the two young protagonists. Indeed, his works are characterized by a personal, intimate and reserved style, as well as by his preoccupation with everyday affairs, and by a strong connection with Ukraine.

Indeed, his works are characterized by a personal, intimate and reserved style, as well as by his preoccupation with everyday affairs, and by a strong connection with Ukraine.

In Ukraine, Aleichem lived in different cities such as Kiev, Lviv and Odessa, which was home to a large Jewish community until the days of the Shoah. He also traveled and lived in the small Jewish villages of Ukraine before moving with his family to the United States in 1905, after having been ruined by his bad economic decisions of speculation on the Kiev stock exchange. It was about this episode in his life that he wrote his account of speculation “Der spekulyant” (“The Speculator”), depicting his own tragic experiences. In New York he was very well received by the press and by Jewish and American society. Earlier he tried his hand at the theatre. He premiered his drama “Tsezeyt un Tseshpreyt” (“Scattered and Dispersed”) in Warsaw, which was successfully performed on the Polish stage, but could not be performed in Ukraine, due to misgivings on the part of the Russian authorities. It did not go well in the United States, so much so that he had to return to Europe afterward, although later he did return to New York. It was there that he was dubbed the “Jewish Mark Twain.”

In 1888 Aleichem founded a literary almanac modeled on the most important European literary magazines, but in Yiddish, under the name “Di yidishe folks-bibliotek” (The Library of the Jewish People). This became a milestone in the history of modern Yiddish literature and helped Aleichem to gain recognition throughout Europe and even in the United States. However, after the publication of the second volume in 1889, he went bankrupt and had to bring this valuable project to an end.

Aleichem never stopped writing, and thanks to him, Yiddish gained cultural, artistic, literary and academic status, as well as crossing national and artistic borders, reaching its apex after his death with “Fiddler on the Roof.” In this story of Tevye “the milkman,” Aleichem creates an imaginary place that is Kasrilevka, which will timelessly represent the figure of the archetypal shtetl. The prototype of Kasrilevka was the Ukrainian village of Voronkov, where Aleichem grew up.

Aleichem never stopped writing, and thanks to him, Yiddish gained cultural, artistic, literary and academic status, as well as crossing national and artistic borders…

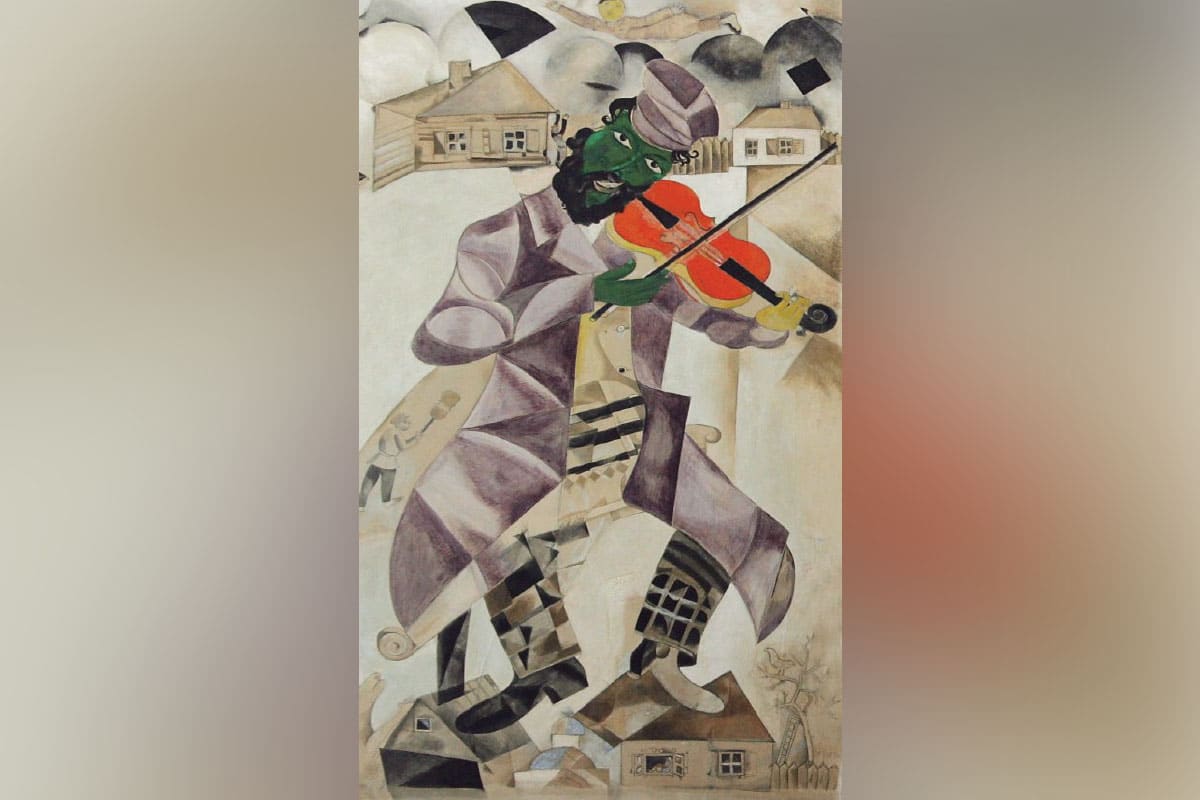

“If I Were a Rothschild” (“Ven ikh bin Roytshild”) is a monologue written by Aleichem in 1902 with reference to the iconic figure of the Rothschild family as the epitome of European Jewish wealth. This would posthumously inspire the centerpiece of “Fiddler on the Roof,” the most important Jewish theatrical and cinematic work, after his death. “Fiddler on the Roof” is also a metaphor for the people of Israel in exile in the face of the many changes and challenges that fate throws at them over time and places. Aleichem’s Yiddish and Jewish colleagues and friends supported him and his family with donations, among them IL Peretz, Jacob Dinezon, Mordecai Spector and Noach Pryłucki, until on May 15, 1916 Aleichem departed his material shtetl for an immaterial one due to tuberculosis.

His funeral was the largest ever seen in New York City, more than 150,000 mourners accompanied the writer’s coffin from his home in the Bronx to the Ohab Tzedek synagogue in Harlem, down Fifth Avenue to the Lower East Side and finally to Mt. Nebo Cemetery in Cyprus Hills, Queens. The New York Times reported not only on the nature of the funeral, but also on Aleichem’s request not to be buried “among the aristocrats and the powerful,” but “among the people themselves.” Moreover, he wanted to be buried in Kiev next to his father’s gravestone. And, despite the significance of his death and funeral as a historical event, the man, the writer, the symbol, died virtually alone, isolated, poor and ill.

Sholem Aleichem is more than a classic; he is a symbol of the Jewish people and its survival. Aleichem’s memory lives on: In Ukraine there are several streets in different cities named after him, plus the symbolic statue in Kiev. In Israel, in the city of Natanya, there is a statue of him, plus the number of streets named after him in the Hebrew country. In Moscow there is another statue and in New York a street is named after him. On Broadway he is remembered as the writer of one of the most important musicals in its history. He is therefore a universal figure who should also remind today’s world that peace is possible. He was Jewish, but also Ukrainian. He lived through antisemitism, specifically the pogroms, which prompted him to emigrate. His legacy is invaluable for European Judaism, Israel and world culture.

David A. Rosenthal is a political scientist, journalist and international analyst. Follow him on Twitter @rosenthaaldavid.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.