When the topic of costume begins to reverberate throughout the halls of our schools, then I know that the holiday of Purim is quickly approaching. There is a palpable excitement in our community for Purim, and not just for children. The festivities surrounding the Jewish Mardi Gras bring together joy and silliness, reflection and chaos, transforming adults into costume-wearing adolescents, converting our holy spaces into holy madness. It is important that we maintain our traditions of light-hearted silliness for our children, that our community members of all ages receive a respite and revel in the experience of our shpiel. At the same time, it’s crucial that as adults we pause and acknowledge that the underlying assumptions of Purim resonate differently this year after more than 500 days of war with Hamas. Whereas before the attack and massacre of Oct. 7 we wore masks only once a year, now we wear masks every day.

It’s time for a new type of costume.

Costumes and masks are the physical manifestation of the topsy-turvy lesson of Purim: Nothing is as it seems. Within the Book of Esther, the royal power is a bumbling fool. Our holiday’s princess earns her place in Jewish lore by winning a surface-level beauty pageant, only later to be revealed as our hero. The genocidal scheming of a Jew-hating villain is undermined by casual events at a party. Most pronounced, God remains hidden within a sacred text about the fragility and resiliency of our peoplehood.

Esther is a disturbing story for a people consumed with rigid order in our lives. Our prayers are structured. Our calendar of holidays is predictable. Our kosher diet is rigid. When an event breaks the construct of our organized lives, our tradition either calls for celebration or for grieving sorrow. Thus, on Purim, the ritual of wearing costumes demarcates the unusual changes of the day.

In addition to the general theme of royal banquets throughout the Book of Esther, the costume changes stand out as a motif of the narrative. Ahasuerus appoints Esther as queen by setting the royal crown atop her head (Esther 2:17). When Mordecai learns of the plot to annihilate the Jews, he changes his clothes to sackcloth (Est. 4:1). Later, when Ahaseurus wants to honor Mordecai, the king directs Haman to dress Mordecai in royal garb and parade him throughout the city (Est. 6:11). Each change in costume represents a pivot within the plot and a change of course in the eventual outcome for our people.

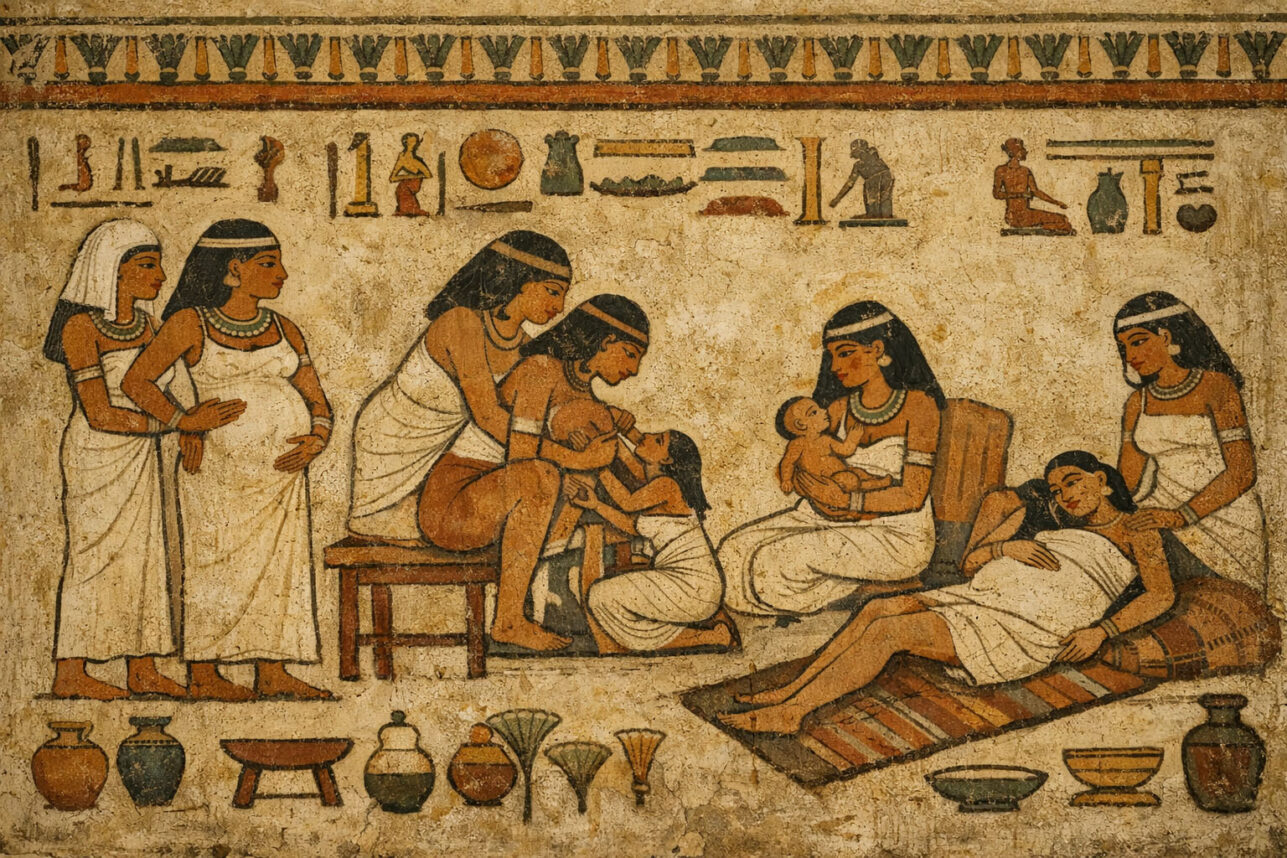

Of course the significance of masks and costumes is not unique to our tradition. The tradition spans from antiquity through the Middle Ages and from the Far East to the West. So iconic of their culture, travelers today bring back Japanese and African masks as souvenirs of their time abroad. Greek drama of the 5th-4th centuries B.C.E. featured a distinctive aesthetic of masking its actors on stage. On the surface, this allowed male-only casts to function as female characters and deities. Yet, there is a deeper level when we consider the self-reflexive moments in which the appearance of the masked actors is highlighted in their own dialogue as seen in the dramas penned by Euripides, and in the Socratic essays by Xenophon. Those moments point to a connection between one’s outward appearance and one’s inner psychological state.

Since Oct. 7, our psychological state as a people has oscillated between devastation and optimism, grief and hope, helplessness and strength. Over the last 18 months, our people have ridden the roller coaster of emotions presented in Esther. While on Purim we are used to seeing the celebratory masks of royalty (along with the celebratory costumes of Dodgers baseball and Disney princesses), we are unaccustomed to Mordecai’s despair expressed in sackcloth or the Jewish people’s fearful reaction to our pronounced date of death. Yet, this year, we have seen those masks on display as well. Should we consider wearing costumes of sackcloth? Should our costumes reflect our inner anguish?

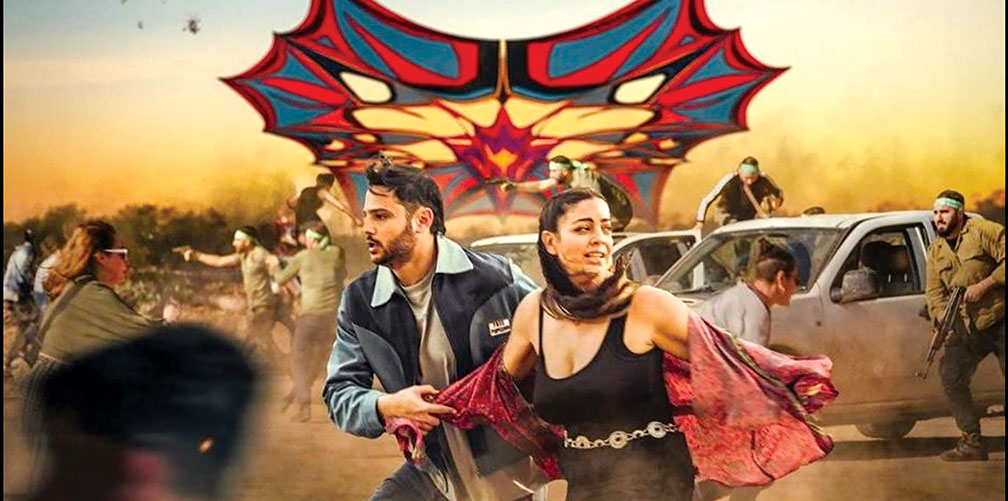

The defining costume expressions of our people since Oct. 7 have included: the bloodied sweatpants of Naama Levy as she was shoved by barbaric Hamas terrorists into a jeep; Noa Argamani’s arms covered in her long green jacket as she pled for help during her kidnapping atop a motorcycle; the war cabinet’s Gadi Eisenkot’s nondescript grey polo worn during his son Gal’s funeral after a brave death in battle; Jon and Rachel Goldberg-Polin’s shirts torn open seemingly to allow their souls to spill out from their crushing despair at their son Hersh’s funeral; and Yarden Bibas walking onto the abhorrent Hamas graduation stage in a running suit with an inquisitive expression concerning his family’s whereabouts after his release from captivity. Consequently, each of them has been forced to wear a different type of mask — one that shields the pain.

There will never again be a Purim when we don’t imagine Ariel Bibas walking along in his Batman mask and cape as a symbol of our collective childhood lost.

There will never again be a Purim when we don’t imagine Ariel Bibas walking along in his Batman mask and cape as a symbol of our collective childhood lost. The macabre scene of Palestinian civilians, including Palestinian children, watching and celebrating before the Bibas children’s coffins might only remind a student of history of the black-and-white images of the mass murder of Jews before crowds of spectators in the forest of Ukraine in Babi Yar in 1941. This is no longer black-and-white. Long before the Shoah, the Book of Esther presented to us the notion that it is possible for a society to be approving, even amused, by the annihilation of the Jewish people. The Bibas boys will be missed at every Purim celebration across the world this year. I hope and pray that the Bibas brothers hold hands as their mother leads them in the heavenly Purim costume parade.

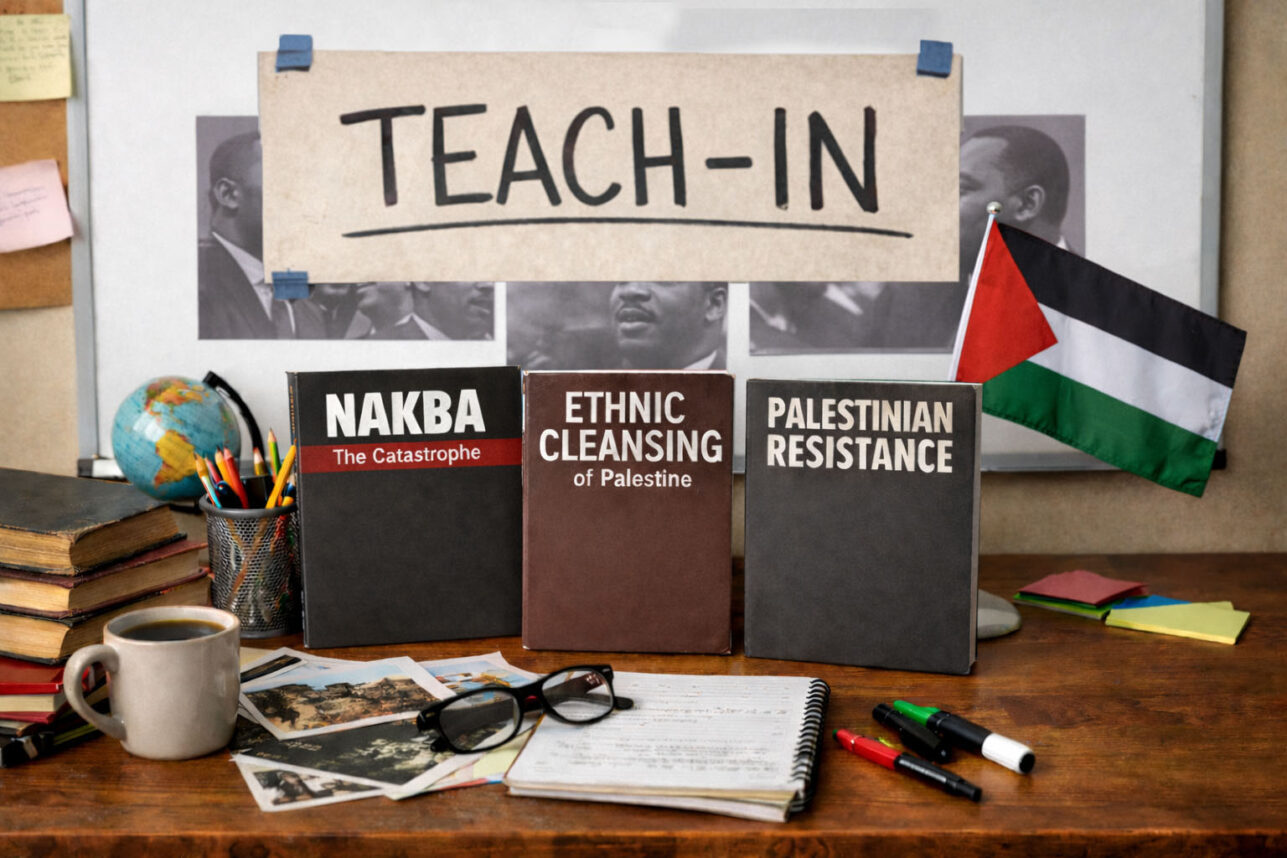

American Jews have been forced to wear our own type of mask as well. Our mask hides a sense of shock that portends more serious trouble. We watch our media spread libelous allegations about the Israel Defense Forces. We see elite university campuses descend into moral bankruptcy. We hear the deafening silence of our neighbors. We read the statistics of the rising tide of Jew hatred across the world. In spite of all of it, we wake up each morning and wear a mask demonstrating normalcy and head to Starbucks for our morning coffee.

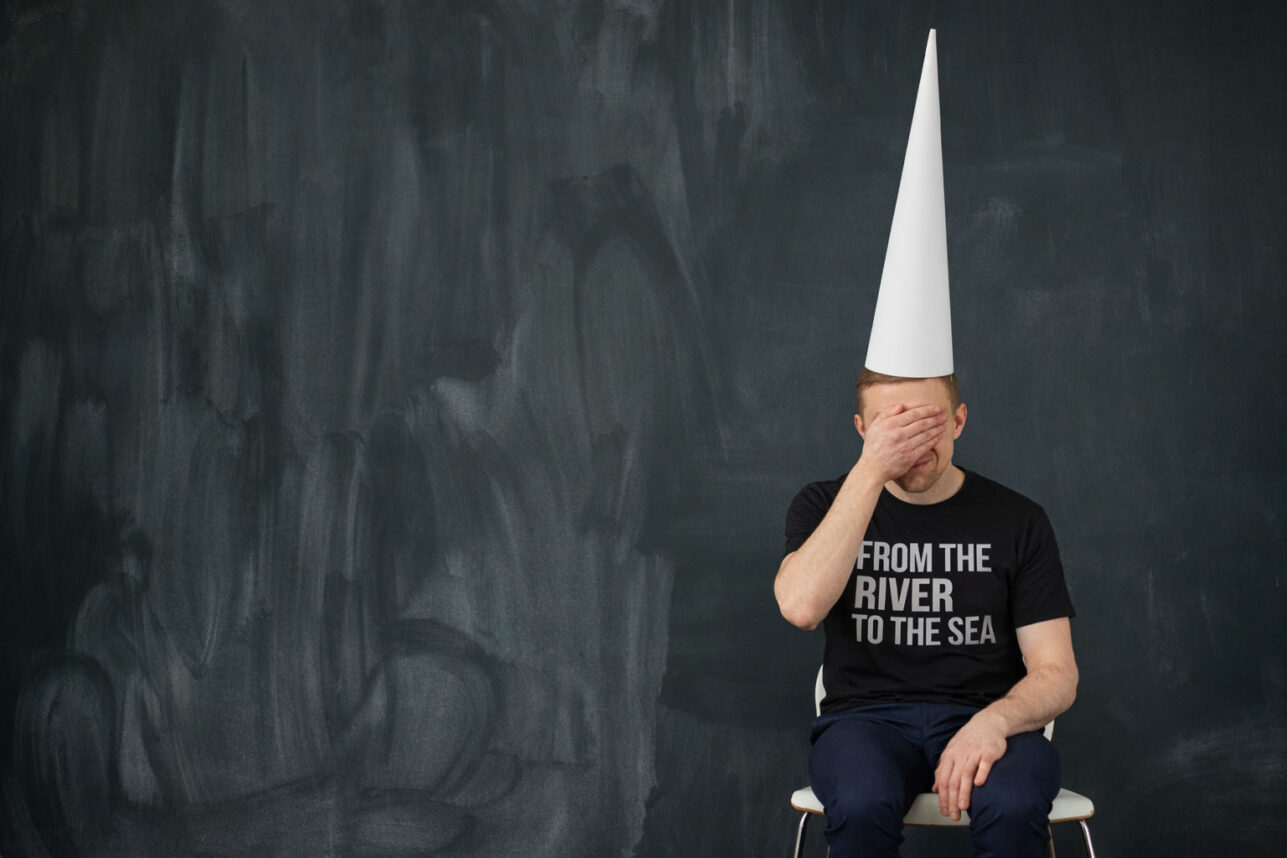

The truth is that so much of the last year and a half has been defined by our adversaries wearing face coverings to mask their identities and our willingness to show our faces. The position of the pro-terror, pro-Hamas, anti-American, Palestinian flag-carrying mobs ought to carry shame. Palestinian barbarians paraded with their faces covered and their machine guns exposed in front of coffins of murdered Jewish children. Bullies wearing face coverings tore down posters of our hostages. Brainwashed collegiate cowards marched wearing keffiyehs while Jewish students sang songs of hope and peace. We are nothing like them. We believe so much in the truthful nature of our message and the righteous cause of our people that we have no reason to mask our identities.

What makes the tradition of masks on Purim unusual for us is that we are a people encouraged to bare our soul. We learn that Moses enjoyed a relationship with God of panim el panim, meaning face to face (Deut. 34:10). That is the goal for the way in which we treat one another. We are a people that believes in face-to-face contact. We believe that our faces reveal insight into our inner lives. As Proverbs teaches, “A joyful heart makes a cheerful face. A sad heart makes a despondent mood” (Prov. 15:13). I can quote many examples, but the truth is that we have been mistakenly conditioned to not bare our souls often enough.

As Purim approaches this year, I think we need to remove our current masks that continue to assure our communities and our families to remain calm. We must pry open our souls. This Purim feels to me more reflective, more spiritual than in years past, perhaps closer to Yom Kippur. For on Yom Kippur, we carry the tradition of costumes of white pointing to purity, we carry the charge of accountability aspiring to honesty, and we read liturgy that is truly sobering.

As Purim approaches this year, I think we need to remove our current masks that continue to assure our communities and our families to remain calm. We must pry open our souls. This Purim feels to me more reflective, more spiritual than in years past, perhaps closer to Yom Kippur.

Our purity of heart this year must be one of Jewish peoplehood. That purity allows us to stand vulnerable before the pain of our brothers and sisters in Israel and across the world, before the strength of the IDF and Jewish spokespeople defending us on social media, before the responsibility of Jewish leaders drawing on every resource possible to craft a bright Jewish tomorrow. That honesty rests in an intellectual outlook that comprehends that we cannot go back to Oct. 6 in any manner. We must remain hopeful, but we must never again be naive. The Megillah crafts for us a drama that is so mature, so sobering in effect that we are encouraged to counteract it by wearing silly costumes, by creating disruptive noise, and by drinking schnapps. While it is always true that Esther is the most sobering account in the Hebrew bible, this year stands out as the most sobering year and a half since the Shoah.

Perhaps it is based on a year like this that the Jewish tradition draws a connection between the two days of Yom Kippur (Ki-purim) and Purim. According to our mystical tradition, the holidays of Yom Kippur and Purim are two sides of the same coin (Tikkunei Zohar 57b). When one looks inward at his or her own reflection in the mirror, one may decide that he or she is alone with God. That is the case of our atonement on Yom Kippur. On the other hand, if one stares at his or her own reflection in the mirror, he or she might decide that they are totally isolated. That is the case of Purim. The author of the Book of Esther does not see God as accountable for the Book of Life.

The Purim narrative reinforces the Zionist ethos: Our people cannot rely on anybody but ourselves. We cannot wait for others. We cannot even depend on God. We are responsible for ourselves. That is why it always makes sense to me that kids wear superhero costumes on Purim. The Book of Esther cries out for a stabilizing force for a turbulent world. It cries out for a Superman, a Spider-Man, or a Batman to restore order.

In the last eighteen months, I have met so many Jewish heroes. I have met courageous IDF soldiers fighting for a Jewish future for Jews everywhere. I have sat with resilient college students, not intimidated by filthy, masked bullies. I have forged new friendships with post-Oct. 7 allies who know what it means to stand by our side. I have spoken with authors, speakers and advocates for Jewish people, American values and Western values who lead the fight against unabashed, uncivilized Palestinian terror-fueled Jew-hatred. All of these meetings have led me to a realization for this Purim.

We might have been people who wore masks to cover our faces to pretend on Purim, but I won’t cover my face anymore. We might have been a people who dressed as villains, but I don’t find evil amusing anymore. We might have treated Purim as a nonserious holiday, but I refuse to think that anymore.

The Book of Esther presents our people with a story that teaches us that the world is unstable, hatred manifests faster than we can imagine, and Jewish leadership is required. To survive as a Jewish people, we must find strength through one another. Sometimes, that strength must indeed take the form of killing our enemies. Always, that strength has to serve as support, comfort, encouragement and love.

The heroism we seek is not going to come in the form of webs or fancy cars. Our heroism will not take the form of spandex and a giant “S” on our chests. Actually, the costume is fine. But, this year, I prefer a giant “J.”

We have proven ourselves to be Super Jews. This year as we look into the giant carnival mirror known as Purim, I hope we see our inner Super Jew. The one that stands for noble values like truth, wisdom, justice, our tradition and our sense of peoplehood. I hope we take pride in the giant “J.”

We are the answer that we so desperately seek. We are the truth, the strength, and the light. We are so much more than ourselves when we stand together. Please take off your masks, open your hearts, bare your souls, and gaze into the eyes of your fellow Jews. For it is only in their eyes that you can recognize whether you need to offer more love and support.

Please take off your masks, open your hearts, bare your souls, and gaze into the eyes of your fellow Jews. For it is only in their eyes that you can recognize whether you need to offer more love and support.

After all, the Megillah ends with Mordecai earning his “J.” The Book of Esther ends with the following verse: “For Mordecai the Jew … was highly regarded by the Jews and popular with the multitude of his brethren; he sought the good of his people and interceded for the welfare of all his kindred” (Esther 10:3). Each of us has the ability to award the “J” to one another. Stand up this Purim and earn your “J.” The future of our entire people depends on it.

Happy Purim!

Rabbi Nolan Lebovitz, PhD is the senior rabbi at Valley Beth Shalom in Encino and the author of “The Case for Dual Loyalty: Healing the Divide Soul of American Jews.”