A young Yazidi girl rests at the Iraq-Syrian border. Photo by Youssef Boudlal/Reuters

A young Yazidi girl rests at the Iraq-Syrian border. Photo by Youssef Boudlal/Reuters It was well before dawn on Aug. 3, 2014, when fighters for the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) streamed out of the northern Iraqi cities of Mosul and Tal Afar, heading east. By daybreak, the Kurdish forces protecting the region’s civilian population had melted away. They fled with few warnings to the villagers, most of them Yazidis, members of an ancient and oft-persecuted religious minority.

The hundreds of settlements dotting the region, known together as Sinjar, are the locus of the global Yazidi population, which counts about 1 million souls worldwide. Across the arid expanse, the ISIS fighters who overran it seemed to follow the same script: Men and women were separated. Prepubescent boys were kidnapped for indoctrination as ISIS fighters. Women and their young children were sequestered into sexual slavery. And the men — those older than 12 — were forced to convert or else murdered, either shot in the head, sprayed from behind with bullets or beheaded as their families watched.

The picture painted in United Nations reports is dim. Within days, 5,000 were dead and about half a million displaced from their homes. One report, in June 2016, called the genocide “on-going,” estimating that 3,200 Yazidi women are still held as sex slaves by ISIS — bought, sold and raped by some of the same men who murdered their husbands and fathers. The bulk of Yazidis in Iraq who remain free stay in squalid refugee camps where basic needs are met barely or not all, while an untold number have embarked on the journey west, over perilous seas to the uncertain promise of refuge in Europe or the United States.

What’s worse is that the genocide of this tiny religious group didn’t take its victims by surprise. “We had a sense that it’s going to happen,” one Yazidi activist in Houston, Haider Elias, told the Journal.

In fact, ISIS has been remarkably forward about its genocidal intentions. “Unlike the Jews and Christians, there was no room for jizyah [ransom] payment,” explained an article in Dabiq, a glossy ISIS propaganda magazine. “Their women could be enslaved unlike female apostates who the majority of the fuqaha [Islamic jurists] say cannot be enslaved.”

A group of Islamic law students reviewed the Yazidi question, Dabiq reported, and ruled that unlike Jews and Christians, who are monotheists, Yazidis are pagans to be exterminated in preparation for Judgment Day. (In fact, Yazidis are monotheists whose Mesopotamian creed predates Islam by thousands of years.)

The Obama administration helped break a siege that stranded thousands of Yazidis on Mount Sinjar shortly after the Aug. 3 massacres, but it was a brief show of American airpower. The United States has done little else to ameliorate the situation; the West can claim neither ignorance nor impotence.

A handful of Jewish organizations have raised the alarm, including the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and at least one, IsraAID, has even offered on-the-ground assistance (see sidebar). But with the global population of forcibly displaced people topping 65 million, most of civil society is tuned to the larger picture. A network of Yazidis in the U.S. seeks its aid and protection for their coreligionists, but their numbers are few.

Iraq is one of the seven countries whose citizens are banned from entering the U.S. for at least 90 days, according to President Donald Trump’s recent executive order. The order makes an exemption for religious minorities, but at present, the procedures for exercising that exemption are unclear. At press time, the order had been blocked by the courts and was awaiting appeal, but the constitutionality of a religious exemption appeared murky in the first place. Meanwhile, the president has promised “safe zones” in Syria but the majority of Yazidis in the Middle East are in Iraq.

The persistence of genocide into the second decade of the 21st century makes a cruel joke of “never again,” just as Rwanda, Bosnia and Cambodia did in the second half of the 20th century. More than two years after the Yazidi genocide began, the question remains: Shouldn’t we do something about it?

‘Nobody helped’

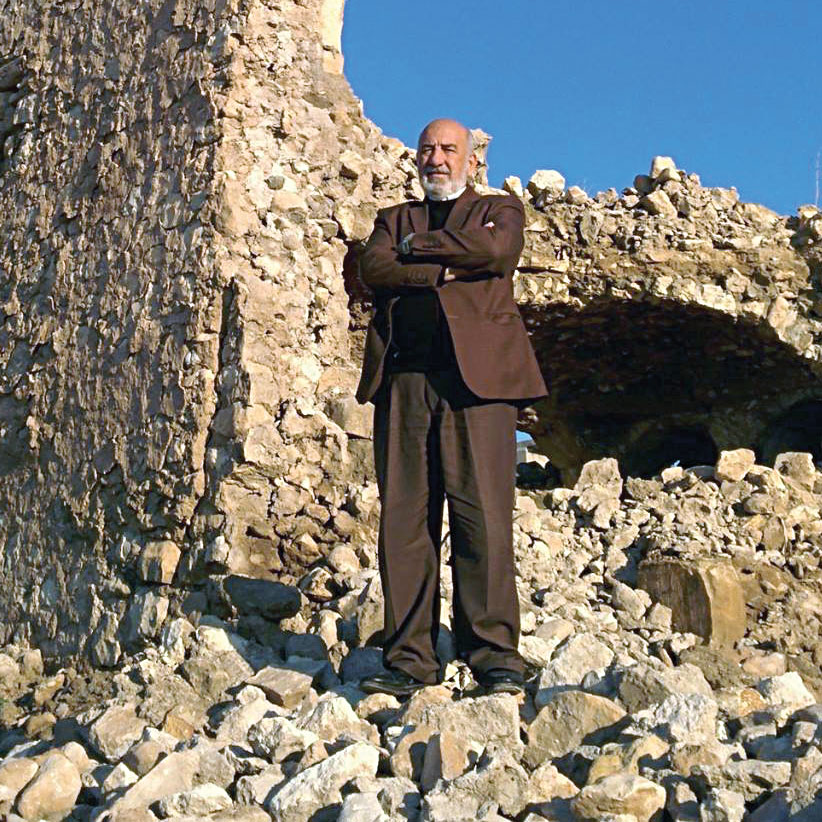

Salem Daoud is Mir of the Yazidis in the United States, the community’s chief religious functionary, serving alongside a council of elders. He speaks a halting English that would be difficult to fully comprehend even if he weren’t describing some of the most trying days of his life. So his son, Seif, who goes by Sam in the U.S., and Rabbi Pamela Frydman, an activist in Los Angeles, joined him on a recent conference call from Glendale, Ariz., to make sure he was understood.

In such a tiny community, no family is unaffected by an event on the scale of the genocide. Salem’s sister and brother-in-law were kidnapped and then rescued six months later; they’ve never been quite the same since, Salem said. It’s hard to know what to ask a person who sat, more or less helplessly half a world away, while his relatives and countrymen were slaughtered and enslaved.

When Salem’s phone began to ring in early August 2014, there was little he could do to help the man on the other end, a local leader in Sinjar by the name of Ahmed Jaso.

“Till the last minute, till before they killed him, he was calling my dad, like, every, I would say, hour,” Sam said on the phone. “And he’s saying, ‘Do something for us, to save us from their hands.’ ”

Jaso was in a village called Kocho, where ISIS troops were lining up the villagers in groups of 60 or 100 and demanding payment to spare the locals’ lives. When the ransom was not forthcoming, they killed residents in a hail of gunfire, Jaso told Salem. Sam explained that his father has many contacts, people who might have been able to help, “whether here in the U.S., in Iraq, Russia, to people in Germany” — even people close to the White House. “Everybody put their hands on their eyes and their ears,” Sam said.

“[Jaso] would call, ‘[ISIS] said they just killed a hundred, so we need support to save the rest. … They killed another hundred, they need money.’ ” he said. “But nobody wanted to pay.”

“We give the information to a lot of people,” Salem added in his imperfect English. “Just nobody helped. No government, and nobody.”

The village of some 1,800 people was cleared out — the men slaughtered, the young boys kidnapped, the women enslaved.

“Very hard time, that was,” the Mir said. The last time he called Jaso back, the local leader was awaiting his turn at the death squad. “The last time, I hoped I’d be one of these people with them,” Salem said.

The activist

Frydman — known more commonly as Rabbi Pam — is a recent arrival to Los Angeles from Northern California, having moved here in May. There, she started the San Francisco congregation Or Shalom Jewish Community 25 years ago and spent a decade as a social justice activist and educator.

One January morning, Frydman sat down in front of her laptop at a Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf on Pico Boulevard. In front of her, a manila folder contained a manuscript of a book about the Holocaust she’s writing that she put on hold two years earlier, when she first learned about the genocide of Yazidis and Assyrian Christians in Iraq and Syria. She finally was finding time to get back to work on the book. Asked to describe how she became active in the struggle for Yazidi survival, she scribbled an impromptu timeline on the back of the manila folder.

In November 2014, Frydman saw an email from the Board of Rabbis of Northern California about an event at a Jewish Community Center in the Bay Area. “It said, ‘Act before it’s too late,’ ” she recalled. At the gathering, she saw footage of Yazidis being marched up to the heights of Mount Sinjar, where they were trapped.

“We heard about children who were dehydrated because there just wasn’t enough water,” she said. She heard a story about a woman being driven up the mountain by ISIS forces and struggling to carry both of her children — one of many such stories to emerge from these forced marches. When this particular woman grew too exhausted to hold both children, she put one of them down.

“As soon as she put that child down, the child was slaughtered, was killed, and I said to myself, ‘This is a death march! This is what our people went through in the Holocaust!’ ” Frydman said, her voice wavering. “The fire was in my belly and my heart was shattered, and I felt that I had to do something. And I returned to my home and I started to contact Jewish and interfaith colleagues, and I said, ‘What are we gonna do?’ ”

Soon, she organized a program called Save Us From Genocide, a consciousness-raising campaign for the plight of the Yazidis and Assyrians, hosted by four Bay Area interreligious councils in concert with the United Religions Initiative, a global interfaith network. A project of Save Us From Genocide administered by the Northern California Board of Rabbis, called Beyond Genocide, hopes to gain attention and relief specifically for atrocities perpetrated against Yazidis.

In addition to helping finance university scholarships for Yazidis studying outside Iraq, Beyond Genocide assists in Yazidi migration and resettlement. On that last score, Frydman could describe her efforts only in vague details, out of abundant caution against putting Yazidis in danger.

Asked how much Beyond Genocide had raised for resettlement, she responded, “A very small amount. But with this very small amount, we have performed miracles.”

‘My brother’

Frydman’s resettlement and advocacy work runs primarily through tight-knit networks of American Yazidis such as the one operated by Saeed Hussein Bakr, whom she calls “my brother.” Bakr arrived in the U.S. about five years ago and found his way to Phoenix, where currently he works as a cook for a local Panda Express. As the disaster in Sinjar unfolded, groups quickly sprang up among American Yazidis to help those fleeing for their lives in the Middle East, managed by people like Bakr.

“Yazidis are not a big community,” he said. “So, almost, we all know each other.”

Headquartered in places such as Lincoln, Neb., the largest American Yazidi population center, these networks raise money when possible, though the community is in large part newly arrived and not a wealthy one. More often, they deploy contacts in the United States, Europe and the Middle East to help Yazidi migrants who find themselves in trouble.

Bakr’s group, Yazidi Rescue, will alert Coast Guard officials in Greece, for example, when a boatload of Yazidi refugees is abandoned or waterlogged in the Mediterranean or Aegean sea. In other cases, they’ll help Yazidi women escape from slavery or help refugees who are imprisoned abroad. There are no rules or standard operating procedures for this type of operation, only dire phone calls to anybody who might be able to do something, whether civilians or government officials.

“Some nights, I can say we help 1,000 people in one night,” Bakr said.

Bakr first became involved after one of his sons, Layth, on his way to the U.S., got on a boat headed to Greece from Turkey. His boat capsized, and some of the refugees on board with him drowned. “That’s why I work to help those people,” Bakr said.

Remarkably, though, his son’s near-death experience in the Aegean Sea was not the most harrowing episode for Bakr. That would be earlier, in August 2014, when Bakr’s son and other relatives were turned out of their homes and driven up Mount Sinjar.

“For seven days, they were in the mountains, no power, no communications. We don’t know at any time if ISIS, they captured them,” he said. “It was horrible days. Those seven days, they were the worst seven days in my life.”

An ancient people long oppressed

The Yazidis are an ancient people, born in the cradle of civilization. Consecrated to one God, they survived through the ages. In each generation, the yoke of oppression found them, and they cried out for deliverance — except sometimes their savior was a long time in coming.

Sound familiar?

“In each and every generation, they rise up against us to destroy us,” Jews recite each Passover. It would be equally true on the lips of a Yazidi.

The parallels between Jews and Yazidis become uncanny at a point. Both are ethnically distinct religions dating to the birth of monotheism. Both have been singled out by Muslim rulers for persecution based on their strange and foreign faith, slandered as perversions of Islam.

But somewhere along the ages, the historical arcs of the two people diverge. Whereas the history of Jewish genocide ends after the Holocaust, Yazidis have had no such luck.

Since the 15th century, Yazidis count 74 farmans against them — literally, decrees, calls by rulers for their destruction that inevitably result in mass slaughter. They’ve faced genocide at the hands of Kurds, Turks and Arabs, mostly Sunni Muslims backed by the Ottoman Empire. ISIS is only the most recent in a long line of persecutors.

More: A sex slave survivor fights back

Invariably, Yazidi customs and belief are offered as the reason for their oppression. The religion has no central texts that have survived the ages, but its folklore is vivid and distinct from any other faith. Adherents claim to descend not from Abraham but from Adam. Their legend has it that Adam and Eve, as a sort of competition, each placed their seed in a jar. When Eve’s jar was opened, it held an unpleasant stew of filth and insects. Adam’s contained a beautiful baby boy, ibn Jar, literally the son of Jar, who became the ancestor of the Yazidi people.

Ironically, it is their guardian angel that has earned them the fanatical ire of radical Islamists. Yazidis regard as sacred Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel, a fallen angel who refused to bow to Adam when God requested he do so, and who consequently gained dominion over the fates and follies of man. This origin story bears a similarity with that of the Islamic legend of Iblis, the archdevil in Muslim theology. The resemblance between the tales has historically motivated the slander of Yazidis as devil worshippers, a kind of Middle Eastern blood libel that continues to claim the lives of its subjects.

“They have made Iblis — who is the biggest taghut [idolator] — the symbolic head of enlightenment and piety!” the article in the ISIS magazine Dabiq exclaims. “What arrogant kufr [infidels] can be greater than this?”

One irony to emerge from this account is that peacocks don’t exist in the region where Yazidi civilization arose. If the community of nations is not watchful, it’s not inconceivable to imagine a Middle East with no more Yazidis, either.

‘Never again requires a lot of energy’

Google searches for “Yazidis” saw a massive spike in early August 2014 and then returned, but for a few small flutters, to a flatline. But things never went back to normal for Haider Elias, a Yazidi activist in Houston who is the president of Yazda, an advocacy, aid and relief organization.

That’s not the role he’d imagined for himself before ISIS began to wreak catastrophe. A former translator for the U.S. Army in Iraq who immigrated in 2010, Elias was raising three children and studying biology as an undergraduate in the hopes of attending medical school. When his brother was murdered in Iraq and the rest of his family displaced from their homes, he dropped his medical school dreams to dedicate himself to advocacy.

Elias and his peers at Yazda run a gamut of programs aimed at helping those displaced by the genocide. They’ve presented on the catastrophe in more than 10 states, including California, and in Europe. In Iraq, the group offers psychological and psychosocial therapy to help reintegrate women who have escaped or been rescued from ISIS. On top of all that, Yazda runs documentation projects to record video testimonies about the genocide and document mass graves.

Elias is still a full-time student at the University of Houston, though he’s switched majors to psychology at the recommendation of some American friends. A social science degree would better suit him for advocacy work, they told him. His days are long and busy, but he’s motivated by the knowledge that his people still face imminent danger.

“Many people want to come back [home] but they’re afraid that the security forces again are going to fail and run away, and this time it’s going to be more fatal, more catastrophic,” Elias said.

And so Yazda now is advocating for international protection for Yazidis, without which resettling Sinjar is unfeasible. “Without some form or guarantee of protection, this community is terrified,” he said.

Elias admits to still being angry. He’s angry with ISIS, naturally, and with the world for standing idly by; but more specifically, he’s angry with the Kurdish fighters, the Peshmerga, for abandoning their posts before the Islamists’ murderous advance.

“It’s not a battle and they lost — they ran away,” he said. “They did not tell the population. When you lose many lives and you think you lost the battle, the first thing you do, you inform the population. The second thing, you run away.” To hear Elias and other Yazidis tell it, the Peshmerga didn’t quite bother with the first.

Though most Yazidis are behind Kurdish lines for the moment, their situation remains precarious and their advocates few. Elias made note of a chilling silence in Congress, broken only on occasion by legislators who represent Yazidi population centers, including two Republicans, Rep. Jeff Fortenberry of Nebraska and Sen. John McCain of Arizona.

“We need a campaign in 2017 to help the Yazidis, whether to advocate for international protection or accepting Yazidi refugees in the U.S. or sending more humanitarian aid to the areas,” Elias said.

Responding to the genocide, Yazda took up “never again” as a rallying cry. But Elias is not naïve about the prospects of his people.

“Never again requires a lot of energy, a lot of passion, a lot of work,” he said.

‘Save us!’

The Yazidi call for aid is neither subtle nor nuanced. Even before the genocide, theirs was a struggle for existence. There is no conversion into the community, and a child with even one non-Yazidi parent is considered to be outside the faith. The massacres and enslavement of Yazidis compound an already dire population problem.

“An entire religion is being exterminated from the face of the earth,” Vian Dakhil, a Yazidi member of the Iraqi Parliament, told the legislature on Aug. 5, 2014, in a tearful plea that briefly went viral on the internet. “Brothers, I appeal to you in the name of humanity to save us!”

Before she could finish the next sentence, she collapsed, weeping.

The Yazidis interviewed for this story made clear they are open to any help they can get — military, political, financial and otherwise. Currently, Frydman and her colleagues are advocating for a real immigration pipeline to allow Yazidis to come to the U.S. notwithstanding the Trump administration’s refugee policy.

The Trump order, before a federal judge blocked the bulk of it on Feb. 3, in theory allowed Yazidi immigration to continue largely unimpeded. In practice, though, the International Organization for Migration, which coordinates refugee admission, has told Yazidi refugees their immigration has been canceled until further notice, Reuters reported. A faith-based exemption raises constitutional questions and its legality is a matter for the courts to decide.

But not all displaced Yazidis want to leave Iraq, anyway. Many simply want to resume their lives in the villages where they were born and escaped death, according to Salem Daoud, the Yazidi Mir. Much of that territory is still held by ISIS.

For now, the totality of a people’s homeland lives in limbo and its diaspora finds only limited means to help them. Often, prayer is the only recourse. Frydman recalled a joint prayer group near Phoenix with Yazidis, Jews and Universal Sufis. After the prayers were over, a Yazidi elder approached her and showed her a tiny book in a plastic pouch. Peering through her bifocals, she discovered it to be the Book of Psalms. A Jewish friend had given it to the elder, he told her, shortly before immigrating to Israel after the declaration of the Jewish state. “He said the prayers in this book will protect me,” the elder told Frydman.

The themes reflected in the Book of Psalms, as it happens, are more topical now for the Yazidi people than they ever have been in recent memory. As it says in Psalm 7:

O Lord, my God, in You I seek refuge; deliver me from all my pursuers and save me, lest, like a lion, they tear me apart, rending me in pieces, and no one to save me.

How to help

LEARN more about the plight of the Yazidis by reading reports from the United Nations, Amnesty International or other news articles.

CALL or write your elected representatives to request that they act on behalf of the Yazidis.

DONATE to organizations working to assist Yazidis through advocacy and direct aid, listed below:

Beyond Genocide

norcalrabbis.org/yezidi-fundraiser

(415) 369-2860

Yazda

yazda.org

(832) 298-9584

IsraAID

israaid.co.il

info@israaid.org

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.