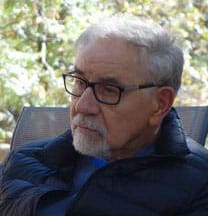

The “Baltimore brothers” taken in August 2019. Bob Porter, always the hub, is in the middle.

The “Baltimore brothers” taken in August 2019. Bob Porter, always the hub, is in the middle. During Bob Porter’s funeral at Mount Sinai Memorial Park, as the rabbi talked about the man’s family and his virtues, I recalled how Bob and I met 65 years ago.

It was 1955 and I was in 10th grade at a technical high school in Baltimore, headed for an engineering career, like my brother. This was my parents’ expectation, as well as mine.

One day, another student joined me at lunch. We both lived in Forest Park, a largely Jewish neighborhood far from our high school, so we vaguely recognized each other. He said his name was Bobby. I told him mine name was Roberto.

“Same name,” he said with a sly smile. He pointed to himself: “Bobby.” He pointed to me: “Bobbo, right?” We laughed and shook hands. He told me his last name was Porter. “Porter?” I asked, implying it didn’t sound Jewish. He shrugged, saying his dad changed it from Krichinsky.

Every day after that, at lunch, Bobby and I met. We talked about poetry, music, art and movies. We raged against 1950s conformity. We were two 15-year-old beatniks-in-training.

One day, in early 1956, he invited me to his house. There, I met his friends. Bobby was the hub, and these guys gathered at his place every weekend. Once I was in Bobby’s house, I never left.

As a group, we went to parties, drank booze, wrote poetry, drew pictures, then drank some more. When lubricated with liquor, we shouted out scraps of literature to one another: Dylan Thomas, Allen Ginsberg, James Joyce, Henry Miller. Bobby’s dad somehow managed to get hold of a banned copy of “Tropic of Cancer,” which fascinated us.

During the summer of 1961, Bobby — now called Bob — and I hitchhiked to California. At a San Francisco day-labor office, we told a clerk we wanted to pick fruit with migrant workers. A noble idea, but we lasted just one day. Sweaty and tired after picking pears, Bob found a note in his pocket with the phone number of the clerk at the labor office. She put us up at her place in the Fillmore district and called us her “Baltimore Orioles.”

During that same trip, Bob and I hitchhiked from San Francisco to Los Angeles. While in Carmel’s 17-Mile Drive, an area of the super-rich, I noticed the roadside mailbox of a nearby mansion with the name of Porter.

“Hey,” I jokingly said, “why don’t you knock? Tell them, ‘You’re Porter, I’m Porter, maybe we’re related.’ ” Without missing a beat, Bob said, “What they’ll probably say is, ‘That can’t be. You see, our real name is Krichinsky … and our only relatives are in Baltimore.’”

By 1963, Bob and I were living in San Francisco. Bob was welcoming with everyone, and it’s through him I met several people who became lifelong friends. One helped me get my seaman’s document, so in 1966, I started working as a deckhand on merchant ships. By then, Bob was an artist and writer in Manhattan, and whenever I was there, between ships, I stayed at his loft.

During the late 1970s, I lived in Israel, but Bob and I always kept in touch. During visits to the U.S., I stayed at his place, and close friends I’d met through Bob stayed at my apartment in Jerusalem.

By 1981, a couple of our Baltimore “brothers,” whom I’d met that fateful day at Bob’s house in 1956, were Hollywood producers, so Bob and I moved to L.A., where we were together again — this time, as writing partners, developing TV shows and writing episodes.

“Bob was welcoming with everyone, and it’s through him I met several people who became lifetime friends.”

During these last four decades in L.A., the Baltimore brothers and our families — our wives, children and grandchildren — have been my extended family. We got together often, to celebrate holidays, special events and rites of passage. And Bob was the linchpin.

A year ago, Bob was diagnosed with an aggressive strain of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Treatment seemed to help — until it didn’t. He died on Feb. 4 while three of us, lifetime friends, morosely sat at a bar, like orphaned kids, and mourned our Baltimore brother.

At Bob’s funeral, as the rabbi talked, I think about the summer of 1958. Bob had turned 18, but I hadn’t yet. Driver’s licenses back then didn’t have photos, and since we were the same height and weight, with the same color hair and eyes, I borrowed his license to go to New York so I could get into bars. For a month in 1958, I was Robert Porter.

But I wasn’t. Not really.

Bob had an omnivorous intelligence, fascinated by diverse topics ranging from mushrooms to the New York art scene, Greek myths to obscure Russian novels and so much more. He never boasted or complained. He was a funny, self-deprecating storyteller and an excellent listener — a man’s man, yet sensitive. He had a proud, natural grace that made people want to be with him.

Although he was an atheist, he was Jewish at heart, so there was a funeral service at Mount Sinai. While his remains were solemnly positioned in their resting place, I thought about how arbitrary life is: What if Bob had not invited me to his house that day in 1956? What would my life have been?

I cannot imagine.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.