As we read in last Shabbat's Torah portion, Jacob left Canaan for Paddan-Aram, not knowing whether he would return, asking for divine help. He negotiated with God — if you protect me and return me safely, only then will you be my God, only then will I worship you. (Gen. 28:20-21)

When Jacob left for Paddan-Aram, he left as a refugee, fleeing his brother Esau, and when he returned to Canaan with his wives and family, he was fleeing from his father-in-law Laban. Even while Jacob was in Paddan-Aram, Jacob says, he lived like a refugee, unprotected, robbed of sleep, suffering heat by day, cold by night. (Gen. 31:10) In between, he passed through what is now Syria, and the region where Jacob spent twenty years serving for his wives and flocks is now part of the territory controlled by ISIL.

My great-grandfather Benyamin left Ottoman Jerusalem for the United States in 1910, when the empire started drafting Jews into its army. And my great-grandmother Farida came from Aleppo Syria in 1913, for the same reason, because she was chosen by her family to shepherd her younger brother and a male cousin to the United States when they were approaching draft age.

Of course there was no modern Syria then, and the whole area, from Syria to Jerusalem, was a province of the Ottoman Empire. Benyamin, like Farida, was a Syrian Jew who followed Syrian nusach and customs.

Farida knew when she left that she would never return to Aleppo. But for the rest of his life, Benyamin hoped he would some day return to Nachlaot, near the market in west Jerusalem, to see his family.

If Benyamin, my Gidau (“grandpa” in Arabic), prayed like Jacob, then most of his prayers were answered — he found work in Manhattan's garment district, raised a family, led prayers in his Syrian shtibl on Rivington Street (to use the Ashkenazi word for an intimate neighborhood synagogue), got to play rhythms on his Syrian doumbek for his great-grandson. But he never did get to return to Jerusalem.

Benyamin and Farida were both immigrants, not refugees. I never met any of my other great-grandparents, and I only know a little about their circumstances. One came from Warszawa (Warsaw), the rest from other places in Europe, and all arrived in the U.S. well before the second World War. I don't think any of them ever expected to return to their birthplaces in Europe. I don't know about the names or the fates of the people they left behind. But if they tried to get into the U.S. just a few decades later, when they would have been desperate refugees, they would have been out of luck.

Make no mistake, hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees were kept out of this country because politicians drummed up fears and put up walls, saying that a wave of Jewish refugees might conceal Nazi infiltrators, that we had to “take care of our own” first, and such — almost ” rel=”noreferrer” target=”_blank”>neohasid.org and the author of

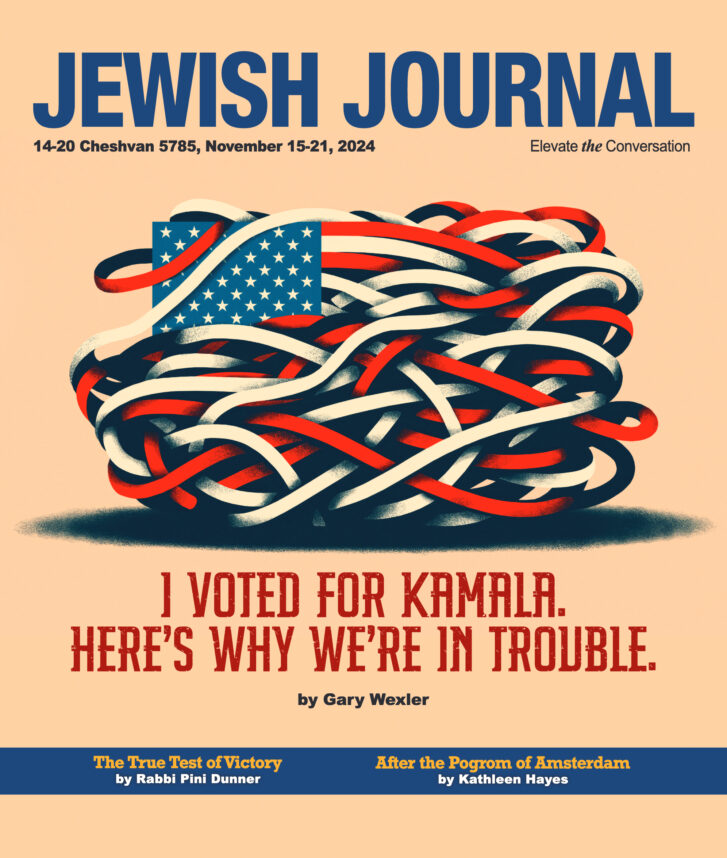

Did you enjoy this article?

You'll love our roundtable.

Editor's Picks

What Ever Happened to the LA Times?

Who Are the Jews On Joe Biden’s Cabinet?

No Labels: The Group Fighting for the Political Center

Latest Articles

Things Done on Highway 61 – Thoughts on Torah Portion Vayeira

Life’s Roadblocks Are a Blessing

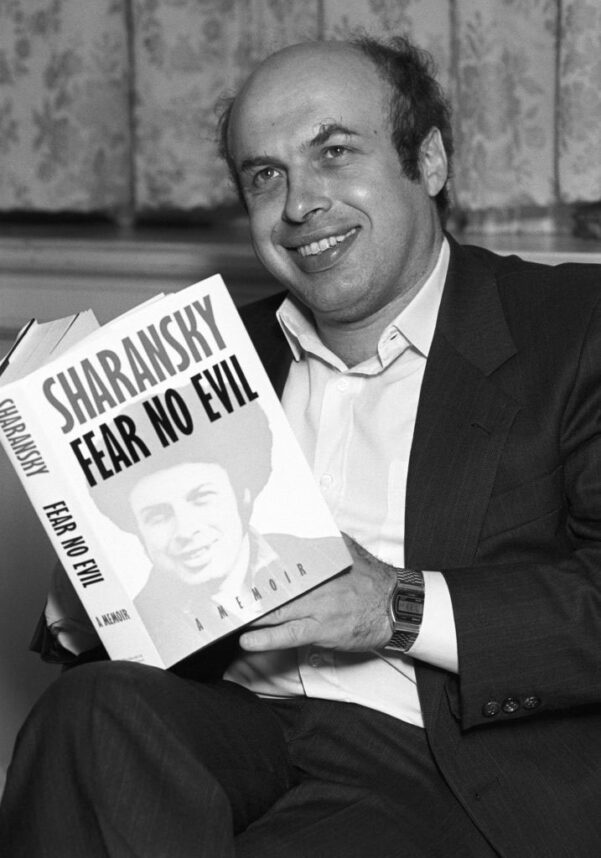

Natan Sharansky Then and Now

A Moment in Time: “We Don’t Visit Israel. We RETURN to Israel”

A Bisl Torah~Stars and Sand

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.