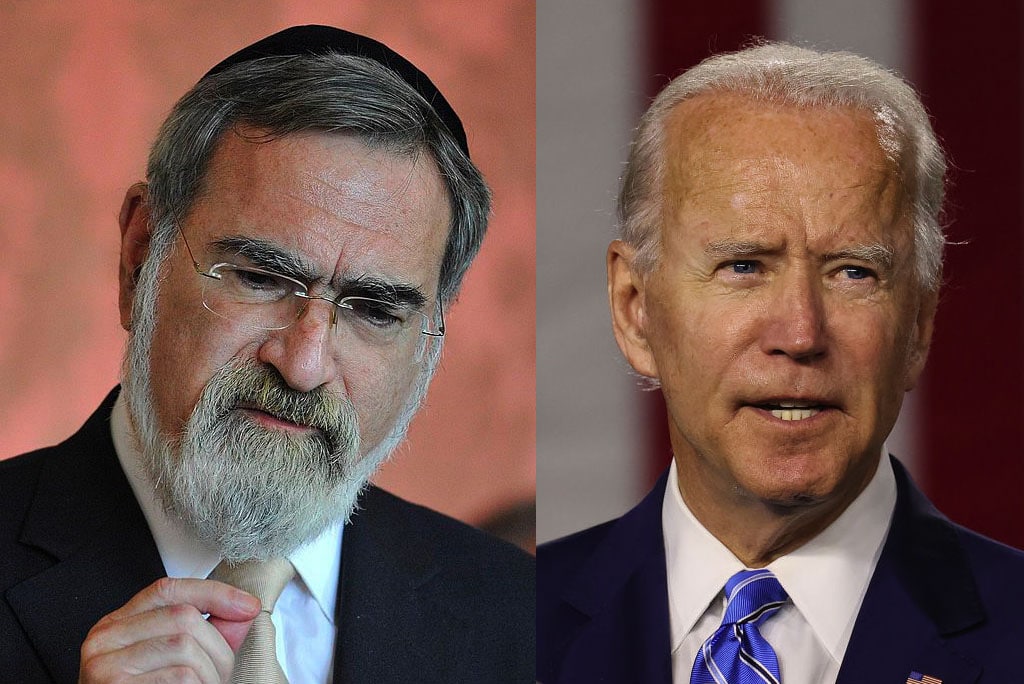

Photos by WPA Pool / Pool and Chip Somodevilla /Getty Images

Photos by WPA Pool / Pool and Chip Somodevilla /Getty Images Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks died on Saturday, just as Joe Biden was declared the President-elect of the United States. An intellectual and spiritual giant leaves us, while a new global leader emerges. Is it possible to connect the two? Can a future leader learn from a Jewish master?

Well, Rabbi Sacks did have much to say about leadership. So, to honor his memory and keep Biden’s future leadership in mind, I thought I’d review the rabbi’s “Seven Principles of Jewish Leadership” which I found on his website.

The first principle is that “leadership begins with taking responsibility.” Sacks contrasts the opening of Genesis with the opening of Exodus. In Genesis, biblical characters are constantly blaming others. In Exodus, Moses takes responsibility and establishes an enduring Jewish value. “At the heart of Judaism,” Sacks writes, “are three beliefs about leadership: We are free. We are responsible. And together we can change the world.”

The second principle is that “no one can lead alone.” The phrase “not good” appears only twice in the Torah, one of them when Moses is rebuked for leading alone. Leadership, the rabbi writes, is “teamsmanship.”

But Sacks adds the important corollary that “there is no one leadership style” in Judaism. During our wilderness years, Moses led by being close to God, Aaron by being close to the people and Miriam “led the women and sustained her two brothers.”

During the biblical era, “there were three different leadership roles: kings, priests and prophets. The king was a political leader. The priest was a religious leader. The prophet was a visionary, a man or woman of ideals and ideas.”

In Judaism, Sacks writes, “leadership is an emergent property of multiple roles and perspectives. No one person can lead the Jewish people.”

The third principle is that “leadership is about the future.” Before you can lead, “you must have a vision of the future and be able to communicate it to others.” Moses had a vision and a destination— leading his people from slavery to freedom and to a land flowing with milk and honey. But before he could finish his task, he had to level with his people about the challenges they’d face in the Promised Land. “He gives them laws,” Sacks writes. “He sets forth his vision of the good society.”

The fourth principle is that “leaders learn.” Without constant study, “leadership lacks direction and depth.” The Torah says that a king must write his own Sefer Torah which “must always be with him, and he shall read from it all the days of his life.”

Citing secular examples from Gladstone and Disraeli to Churchill and Ben Gurion, Sacks writes that “Study makes the difference between the statesman and the politician, between the transformative leader and the manager.”

The fifth principle is “leadership means believing in the people you lead.” Moses was punished by God for casting doubts on the Israelites. The profound principle Sacks cites is that “Judaism prefers the leadership of influence to the leadership of power. Kings had power. Prophets had influence but no power at all.”

“Judaism prefers the leadership of influence to the leadership of power. Kings had power. Prophets had influence but no power at all.”

Whereas power “lifts a leader above people, influence lifts the people above their former selves. Influence respects people; power controls people.”

One of Judaism’s greatest insights into leadership is that “the highest form of leadership is teaching. Power begets followers. Teaching creates leaders.”

The sixth principle is that “leadership involves a sense of timing and pace.” One of Moses’ deepest frustrations “is the sheer time it takes for people to change.” But in the end, Moses comes to realize the “delicate balance between impatience and patience.”

“Moses is saying two things about leadership,” Sacks writes. “A leader must lead from the front: he or she must ‘go out before them.’ But a leader must not be so far out in front that, when he turns around, he finds no one following… He must go at a pace that people can bear…Go too fast and people resist and rebel. Go too slow and they become complacent. Transformation takes time, often more than a single generation.”

The seventh and final principle is that “leadership is stressful and emotionally demanding.” Moses cried out: “I cannot carry all these people by myself; the burden is too heavy for me.” Similar sentiments can be found in the words of Elijah, Jeremiah and Jonah. “All at some stage prayed to die rather than carry on,” Sacks writes.

Why do transformative leaders feel, at times, burnout and despair? Because they see “the need for people to change. But people resist change and expect the work to be done for them by the leader. When the leader hands the challenge back, the people then turn on him and blame him for their troubles.”

Great leaders don’t lead “because they believe in themselves. The greatest Jewish leaders doubted their ability to lead. Moses said, ‘Who am I?’ ‘They will not believe in me.’ ‘I am not a man of words.’ Isaiah said, ‘I am a man of unclean lips.’ Jeremiah said, ‘I cannot speak for I am a child.’ Jonah, faced with the challenge of leadership, ran away.”

Great leaders don’t lead “because they believe in themselves…they lead because there is work to do, there are people in need, there is injustice to be fought.”

But leaders persevere and still lead, Sacks writes, “because there is work to do, there are people in need, there is injustice to be fought, there is wrong to be righted, there are problems to be solved and challenges ahead. Leaders hear this as a call to light a candle instead of cursing the darkness.

“They lead because they know that to stand idly by and expect others to do the work is the too-easy option. The responsible life is the best life there is, and is worth all the pain and frustration.”

There will surely be plenty of pain and frustration in the years ahead for president-elect Joe Biden. But this is the role he chose. May he be inspired by the words of a man who understood well that for great leaders, no matter the pain, “the responsible life is the best there is.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.