Sometime in the late 1970s, when my wife, my older son and I lived in a Jerusalem apartment, there was a knock at the door. Expecting friends, who’d often show up without calling first, we were taken aback at seeing an ultra-Orthodox gentleman in the hallway. He pointed out, with surprise, that we didn’t have a mezuzah outside our door. Without missing a beat, I said, in Hebrew, “That’s because we’re not Jewish.” He was stunned. He stammered a bit, then left.

Of course, what I told him was not true. My wife and I are Jewish. But as secular Jews in a Jerusalem neighborhood filled with ultra-Orthodox who threw stones at our car when we drove on Shabbat, what I said was a joke laced with a bit of venom. Nevertheless, our not having a mezuzah outside our door was not an act of defiance or revenge. We were nonreligious, and it simply had never occurred to us to put up a mezuzah.

In 1981 we left Israel and moved to Los Angeles. In 1983, when my wife was pregnant with our younger son, we bought a house in the San Fernando Valley. Two months after we moved in, our younger son was born, and we arranged for the brit milah to be held at home. When I spoke with the mohel, he asked if we had a mezuzah. I told him we didn’t. He said “Oy,” and took a deep breath.

He didn’t demand or even request that we put up a mezuzah, but his ‘oy’ felt like a sigh and spoke volumes. I went to a Judaica store in Fairfax and bought a mezuzah. I asked about the proper way to install it and was given a sheet with instructions. Though I did not recite a blessing, I followed the rules for placing it at the required angle and location on our doorpost, and I felt good about it, a sense of continuity and connection. When the mohel arrived, he saw the mezuzah and smiled at me, acknowledging the mitzvah. Carefully, he placed his fingers to his lips, then touched the mezuzah with those fingers. A private rite of worship, of connection.

As we chatted with the mohel, it turned out that he had lived in Jerusalem and, miraculously, he had trained with the very same mohel who had performed the brit milah for our Jerusalem-born older son! This struck me as something more than coincidence. There was an aura of continuity and connection about it, similar to what I’d felt when nailing the mezuzah to our doorpost.

For forty years that mezuzah has been outside our front door. It’s still there, still at an angle, still containing that tiny, rolled-up biblical scroll. Each time the exterior of the house gets painted, that mezuzah is carefully removed, and then, once the paint dries, it’s put back, making sure it’s at the same location as before, and at the same angle.

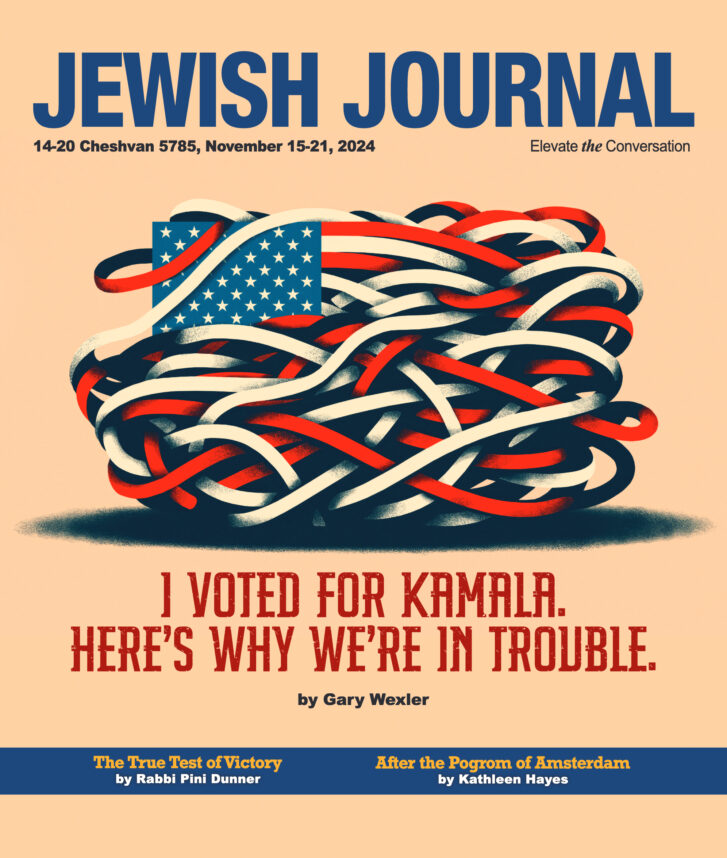

Times, as we know, have changed. Over the past few weeks there’s been a dramatic rise in antisemitic acts, and some have voiced fear about showing openly that they’re Jewish.

I’ve even heard that some have removed their mezuzah so that people delivering mail or Amazon packages, or those working at the house, have no obvious clue that Jews are living there. My guess is that some who remove the mezuzah from its place outside the house then put it in a doorpost inside the house. Others, presumably, hide their mezuzahs.

We will keep our mezuzah just where it is, and it’s not because we’re proud of being Jews, or that we have a religious attachment to the words on that scroll. For us, that mezuzah represents connection and continuity.

My wife and I are not going to do either. We will keep our mezuzah just where it is, and it’s not because we’re proud of being Jews, or that we have a religious attachment to the words on that scroll.

No. For us, that mezuzah represents connection and continuity. It’s a way of saying: We’re Jews and we live here.

This is who we are.

Roberto Loiederman has written more than 100 articles for The Jewish Journal. He is co-author of “The Eagle Mutiny,” a nonfiction account of the only mutiny on an American ship in modern times.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.