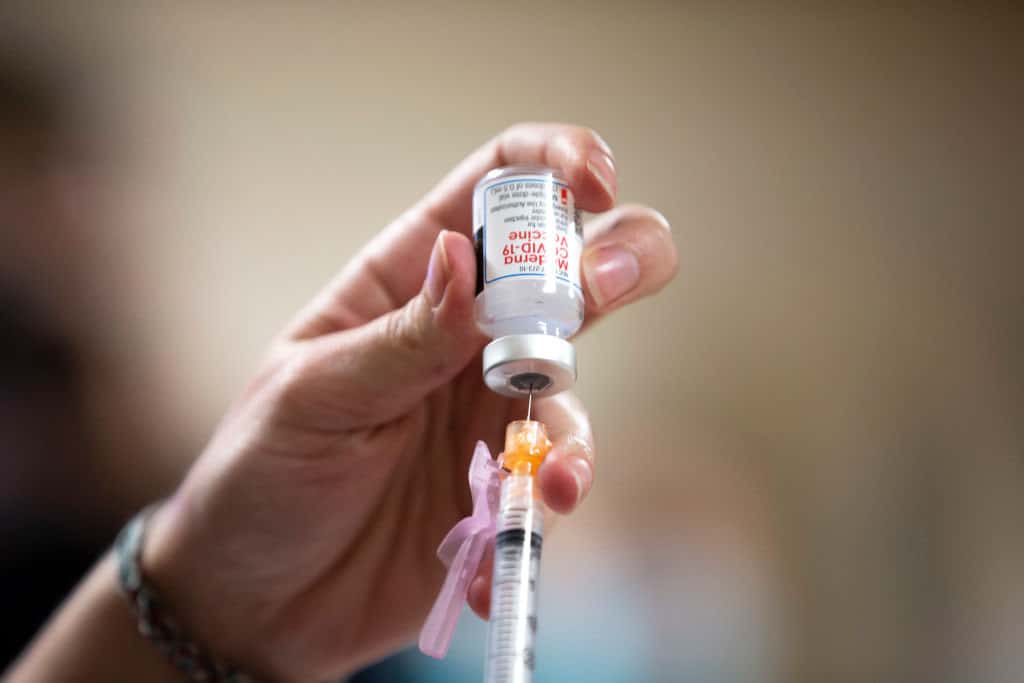

A clinical pharmacist with Seattle Indian Health Board (SIHB) administers a shot of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine to frontline workers at the SIHB on December 21, 2020 in Seattle, Washington. (Photo by Karen Ducey/Getty Images).

A clinical pharmacist with Seattle Indian Health Board (SIHB) administers a shot of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine to frontline workers at the SIHB on December 21, 2020 in Seattle, Washington. (Photo by Karen Ducey/Getty Images). This year of global illness is coming to an end just in time to administer a cure. The predictions in March that COVID-19 would cause millions of American deaths and take years to develop a vaccine were plainly wrong.

Yet, we remain in agony. And for good reason. Well over 300,000 died, and 100,000 businesses were lost. Lockdowns proved to be epidemiologically wise but spiritually and economically destructive. As a species, we have never excelled at isolation. But public health required that we sever human lifelines — the very same common causes and social bonds that enabled human beings to tame this planet.

Feeling cut off and alone can be unbearable. Very few wish to return to our state of nature, which is why stories of shipwrecked castaways and wilderness survivalists are so frightening.

The coronavirus was a stark reminder of how fragile we are, how unprepared we can be for a global crisis and how dependent we are on one another. COVID-19 shocked systems beyond the mere respiratory.

Good riddance to 2020, a year when we ruined our eyesight on Netflix. This year is best left forgotten.

Except we can’t.

We have lived through an epochal, defining moment of history, not unlike 9/11. All that soul-searching while sheltering at home, washing hands feverishly to avoid getting a fever, avoiding all contact — six-feet apart became the new six-feet under. All those outdoor enticements became forbidden, all on account of the deadly droplets of an invisible virus.

With January 1 upon us, those wishing to make New Year’s Resolutions (last years were doubtlessly aborted by a plague), will probably try to make some use of coronavirus self-discoveries.

The sacrifices that the virus required, and the newfound resources it inspired, were everywhere. We made do with virtual gatherings and working from — and working out in — home. Sexual diseases disappeared, the pandemic proving to be the ultimate prophylactic. Meanwhile, the unthinkable happened: we became even more shackled to our screens. Binge watching outpaced binge eating.

Toilet paper and Lysol became precious commodities — yet, it seemed as though there wasn’t anything Amazon wouldn’t deliver right to your door.

We learned that those over 60-years-old were the most vulnerable, which rendered 60 the new 80. Low ceiling, unventilated establishments will probably remain verboten. Some gesture other than shaking hands may need to be invented to seal a deal.

The image of the coronavirus under a microscope, that crown of barnacled nodules, is now forever imprinted on our brains. And its insidious symptoms will probably result in mask-wearing long after everyone is vaccinated. Leaving home without a spare mouth-covering will be like forgetting one’s keys. The mask became a metaphor all its own.

In some parts of the country, the decision to wear a mask was as much a political statement as it was a public health measure. Operation Warp Speed — the government’s initiative to produce a vaccine — fell into a political time warp, a crease in time where we regarded our leaders as warped. Remaining neutral on nearly any issue of the day — especially anything having to do with President Donald Trump — would lead to even worse isolation.

In homes all across America, Trump was either reviled as a murderer who abetted a virus or revered as the second-coming of Jonas Salk. There was no solid ground in-between. Polarization was the endgame of the administration, taking sides an absolute necessity and national obsession. Everyone held a strong opinion about President Trump. Friends parted company, and family members were excommunicated — all for failing to adopt the right extreme.

All the while, breathtaking changes transformed the world, almost in defiance of our respiratory concerns. Peace actually came to the Middle East with the Abraham Accords. At the same time, however, as the year wound down, global Jewry was reminded that Jewish life is still very cheap.

As the year wound down, global Jewry was reminded that Jewish life is still very cheap.

On December 24, the High Court in Pakistan ordered the release of the four men who were convicted of kidnapping and murdering Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl in 2002. The mastermind of the savage crime, who originally was sentenced to death, was now among the four seemingly pardoned.

Who can ever forget the barbaric videotape of Pearl’s beheading? His final words, filmed as a confession but recited as an assertion, declared that he was a Jew, that he came from a Jewish family and that Chaim Pearl Street in Israel was named for his great-grandfather.

A journalist, who in any other era and in any other theater of war would be safe from harm. But not a Jewish journalist with Israeli bona fides, abducted by Islamist captors with such bloodthirsty anti-Semitic aims.

The highest court in the country, where Osama bin Laden managed to live undetected until zero-dark-thirty, reaffirmed that the grisly murder of a Jew whose father is Israeli is not a capital crime worthy of even a life sentence.

If that was not insulting enough, that same week, in Argentina, the man charged with supplying the truck that detonated outside of a Jewish center in Buenos Aires in 1994 (murdering 85 and wounding more than 300) was acquitted and released from prison. It was the worst terror incident in the nation’s history, and yet the assailant has been in and out of jail repeatedly, as if Argentina, which once secreted Adolf Eichmann, can’t decide whether the mass murdering of Jews is a criminal act.

The revulsion that naturally emanates from these injustices are not unfamiliar. Whether they are wrongly accused — such as Alfred Dreyfus, Leo Frank or Menahem Mendel Beilis — or whether their murderers are unjustly set free, Jews have a long history with legal systems that are not impartial when it comes to them.

These year-end pardons of Jew-killers, during a time when all minds are on a cure, provide a jolting reminder that the malady of anti-Semitism may simply be incurable.

Too bad there never seems to be an Operation Warp Speed for such inoculations.

Thane Rosenbaum is a novelist, essayist, law professor and Distinguished University Professor at Touro College, where he directs the Forum on Life, Culture & Society. He is the legal analyst for CBS News Radio. His most recent book is titled “Saving Free Speech … From Itself.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.