(Introduction 2021: Our Torah portion, Chayei Sarah, is a good example of how the Bible changes its rhythm for literary purpose. The Bible is usually very laconic and moves through long periods of time with few words. In this Torah portion, finding a bride for Abraham and Sarah’s son Isaac is described in great detail.

The focus on Rebecca foreshadows her pivotal role (in the next Torah portion) of ensuring that the blessing of leadership is removed from the first born son Esav and transferred to Jacob. We are also given some rather stunning and archetypally significant news at the end of the Torah portion – Abrahams two sons, Ishma’el and Isaac, whom Abraham indirectly or directly tried to kill, reconcile at Abraham’s death. It seems that Isaac goes to live with Ishmael and Hagar, whom Abraham and Sarah had banished.

As we move through the Torah portions of Genesis and anticipate the crises in the stories to come, I continue to find myself in amazement of the literary, philosophic, and psychological depths presented to us. What are these readings communicating to us about the human condition? About the nature of family? As we watch these tales of painful fracture and unforeseen cohesion as arch-types of human existence, the fractures and cohesions in our lives make more sense. Losses, grief and suffering open us up to futures of resilience, repair, and even unforeseen love. The tragic beauty is breathtaking.)

Life Torn and Sewn Together 2021 (adapted from 2020)

Human pain is the backdrop of the book of Genesis, pain that produces visions and sometimes unimaginable fulfillment. Of the many sad, heart-wrenching and ultimately beautiful stories in Genesis, one of the most distressing is that of Hagar. We meet Hagar as the maidservant of Sarai (before she becomes Sarah). When Sarai cannot conceive, Hagar is given to Avram (before he becomes Abraham) as a concubine. Hagar conceives, but Sarai feels slighted. Sarai mistreats Hagar, and Hagar flees.

An angel of God intervenes, and counsels Hagar to return to Sarai. The angel assures Hagar that her own offspring will increase beyond measure. The child of Avram whom she is carrying will be named Ishma’el, “God hears,” because God has heard her prayer. Hagar gives a name to the God who speaks to her – “The God Who Sees Me” – and she names the place where she encountered the angel “The Well of the Living One.”

We don’t know why Hagar must return to Avram and Sarai, but it seems that some great part of the plan that the God of the Bible has in mind requires that Hagar submit herself to Sarai.

Hagar returns, and bears her son Ishma’el. When Ishma’el is a teenager, Sarah bears her own son Isaac, and then insists that Hagar and her son Ishma’el be banished into the desert for some offense of Ishma’el that the Torah does not make quite clear.

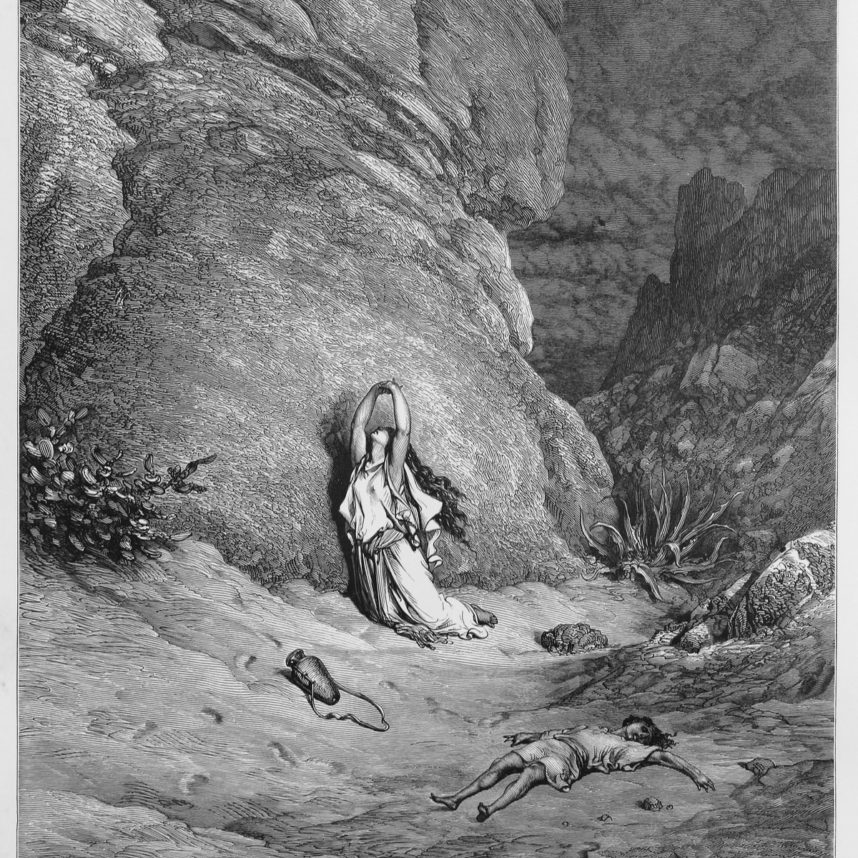

Hagar is devastated; to have returned to the fold, to have submitted, and to be exiled again was too much. She suffers a spiritual collapse. Once she ran out of water in the desert, she resigned herself to the fact that she and her boy would die. An angel intervenes again, and Hagar sees a well of water, and she and her son are saved. The reader assumes that she has returned to the place – and to the well – of the first Divine intervention – The Well of the Living One Who Sees Me.

The rabbinic tradition insists that the story does not end here. In this week’s Torah portion, after Sarah dies, Abraham remarries, to a woman named Keturah – “Incense.” In the Midrash (Genesis Rabbah 61:4), Rabbi Judah says “Keturah is Hagar.”

The brevity of this statement – “Keturah – Zo Hagar” (Keturah is Hagar) is directly disproportionate to its interpretive brilliance. In that brief utterance of Rabbi Judah, many things are brought to light.

It seems that the midrash, through Rabbi Judah, tells us that Abraham loved Hagar. The desperation of barrenness that caused Abraham and Hagar to be thrown together, however begrudgingly, produced a forlorn intimacy. Was their love simply that of two people who quietly asserted their humanity in the midst of lives thrown about in some vortex of destiny? Or had they fallen in love with each other, a love they knew was impossible to fulfill, knowing that they would never, or someday, be together? Or had Sarah’s death released a force that took each of them by surprise? We don’t know, but we are bidden to imagine.

Rabbi Judah’s assertion, in no way supported by the biblical narrative, helps shape a rabbinic theory of love and alternative lives. Rabbi Judah seems to conceive of a God who holds blessings in store that might seem sheer fantasy.

Had the Bible had its way, Hagar would have gone her way, and Abraham would have married a woman of consolation. Rabbi Judah cannot accept this. In saying, “Keturah is Hagar,” Rabbi Judah insists that loose strands of the narrative urge themselves back on each other.

Hagar’s son Ishma’el nearly died – but Ishma’el was Abraham’s son as well. Both of Abraham’s sons nearly died at his own doing. Imagine the tear and trauma in Abraham’s heart – he attempted to kill both his sons, only stopped by angelic intervention.

Might we assume that Hagar/Keturah loved her stepson Isaac like a son, in spite of what Isaac’s mother had done to her? Might we assume that Hagar/Keturah herself was stricken when she heard that Abraham had taken Isaac up to the mountain to be killed as a sacrifice to the God of the Bible? She and her son almost died at the hand of Abraham. Isaac almost dies at the hand of Abraham. Why doesn’t Hagar hate Abraham? Rabbi Judah has us ask different questions. How did she forgive him? How did their love survive?

The text does not report Abraham’s weeping when his son and concubine, Ishma’el and Hagar, were cast from his life forever. Perhaps that inconsolable heartache – and guilt – had led Abraham to take Isaac for a sacrifice. (This is indeed one of my interpretations of the Binding of Isaac – his anger at God and Sarah, his horrific acquiescence, producing unbearable guilt and shame, all caused Abraham to imagine that God wanted him to kill Isaac.)

From Rabbi Judah’s assertion, we can only infer why Hagar had to return to Sarai. So that the love between her and Abraham could be sealed? So that Ishma’el and Isaac could forge a friendship based on their wounded father, their wounded mothers, a friendship that was to be torn but not shredded?

Life can rip us apart. Rabbi Judah wanted us, the readers of the Bible, to be able to sew fragments back together.

Hagar had almost let her son Ishma’el die due to Abraham, to Sarah and due to the will of the God of the Bible, but an angel of God intervened. Abraham had almost killed his son Isaac, due to the will of the God of the Bible but an angel of God intervened. Hagar and Abraham shared a horror, but also an angelic miracle rooted in that horror.

Sarah and Hagar’s sons’ lives were shaped by that horror. We can only imagine their trauma. Was their attending their father’s funeral together a way to face that trauma? We don’t have a record of what the two men said at their father’s funeral. We do know from the Bible that after the funeral, Isaac decided to settle at a place called “Well of the Living (God) Who Sees Me” – it seems certain he went to live with his half-brother and stepmother, Hagar/Keturah.

We must assume that Isaac took his new wife Rebecca there. We might assume that Rebecca got to know Isaac’s stepmother Hagar, and perhaps his half-brother Ishma’el, very well. The stories Rebecca heard are recounted in the yet to be written Midrash of Rebecca.

I am in awe of the genius of Rabbi Judah.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.