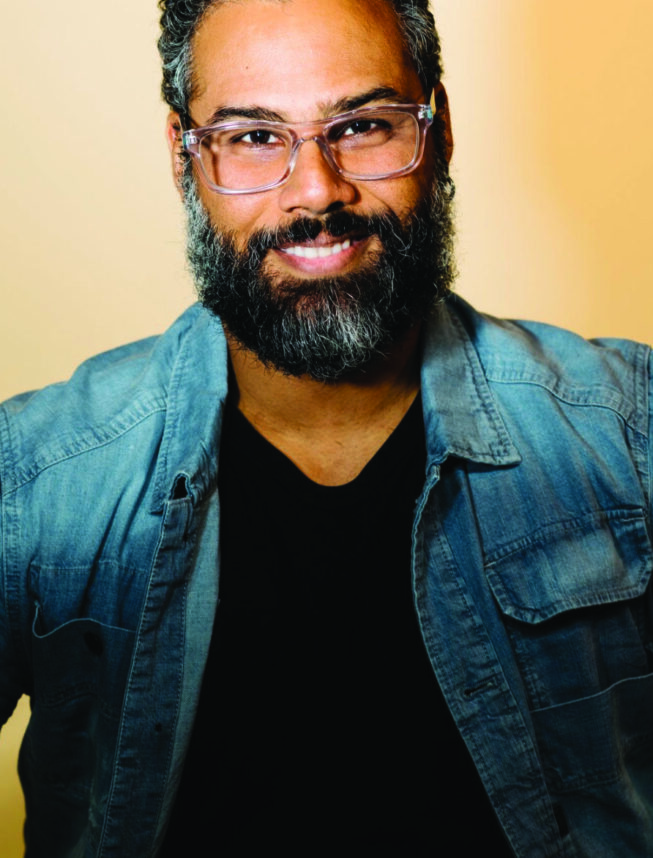

Despite the difficulties wrought by COVID-19, Charles Wiesel, an oleh (immigrant to Israel) from Los Angeles since November 2019, said his first year in Israel has been one of the best of his life.

Wiesel, the Vice President of Business Development for a start-up called “Shahar Solutions” — which developed technology at Ariel University to convert carbon dioxide emissions into natural gas — feels energized by the Abraham Accords and its opportunities for the company as well as for Israelis and Arabs.

Out of both idealism and practical considerations, the partners of Shahar Solutions dream of setting up a manufacturing plant in the Ariel Industrial Park, which is located in the heart of Samaria and already employs some 3,000 Palestinians. To make it a reality, the company is looking towards the Abraham Fund — a three-billion-dollar investment fund set up by the United States, Israel, and the United Arab Emirates to support economic cooperation among them.

By setting up shop in Ariel, Wiesel envisions Palestinians will become an integral part of Shahar Solution’s workforce.

“We, in our hearts and in our actions, are trying to break down some walls,” said Wiesel from his Jerusalem home office. “Now that’s very, very tough. Our Palestinian partner didn’t want to have equity in the company. There are still barriers, political pressure that exist which, in my mind, the Abraham Accords and Abraham Fund will help tear down.”

Among some Palestinians, those barriers have been broken down, at least behind the scenes. Since 2010, the Palestinian Authority has taken a militant anti-normalization stance and forbids Palestinians from doing business with “settlers” in Judea and Samaria. In that spirit, it also boycotted the Abraham Accords, which it accuses of selling out the Palestinian cause. But this ban is difficult to enforce. Some 45,000 Palestinians work in the settlements, mostly in construction and manufacturing. Palestinians rely on their Jewish neighbors for subsistence.

“Ninety-percent of the Palestinian people want peace. No doubt about that,” said Ashraf Jabari, a Palestinian businessman based in Hebron, in a telephone interview conducted in Hebrew. Jabari founded, along with Avi Zimmerman of Ariel, the Judea and Samaria Chamber of Commerce, an NGO designed to develop economic and business ties between Israelis and Palestinians living in the region. “The problem is with the politicians. But many business people and merchants and regular Palestinians prefer peace through the economy more than anything else.”

Jabari led a delegation of Palestinian businessmen to the American-led “Peace Through Prosperity” workshop held in Bahrain in June 2019, despite the Palestinian Authority’s refusal to participate.

“We had to do it if we wanted to be in the picture,” Jabari said. “They [the P.A. leaders] don’t want anyone to make peace except through their door, and that’s a big mistake.”

On October 20, the Judea and Samaria Chamber of Commerce held, virtually, the second annual “Israeli Palestinian Economic Forum,” a “safe space” for Palestinians and Israelis entrepreneurs and business people to come together. It featured a panel on the Abraham Accords and showcased start-ups with an integrated Israeli-Palestinian business model.

Zimmerman considers the Abraham Fund a major opportunity for regional economic development since, unlike past American-sponsored development funds, it does not explicitly discriminate against Israeli institutions and businesses located in the West Bank and Golan Heights. This inclusive approach was reflected in the Trump administration’s policy decision, signed at Ariel University on October 27, to extend funding for scientific research to the area.

Still, the major obstacle to Palestinian-Israeli regional cooperation is the Palestinian Authority, whose political stance has not evolved with that of the Arab states eyeing joint ventures with an economically attractive Israel.

“The Emirates or the Gulf States are much more interested in doing business with Israelis than in creating a Palestinian state,” Zimmerman said.

Jabari said that most Palestinians resent what they consider a self-serving, corrupt Palestinian leadership. For them, the paradigm of the Oslo Accords is no longer relevant.

“Why do we need to go to the end of the world to speak with Israelis, our neighbors?” Jabari said. “We could speak with them directly.”

It’s up to the Palestinians to take the initiative, despite the risks, he said, to leverage the Abraham Accords, whether in the fields of high tech, imports and exports, and incoming Arab-speaking tourism.

“Israel won’t wait for the Palestinians to bring them investors from Arab countries or to sign peace deals,” Jabari said. “If we continue on a true path for peace, we’ll help ourselves. Or we’ll help the Israelis the right way, not through politics.”

Jabari thinks that a peace deal with the Saudis, whom the Palestinian leadership fears, would be the real game-changer.

“If Saudi Arabia will sign a peace agreement for normalization with Israel, no one in the Palestinian Authority will say anything,” he said.

A Saudi deal might also pose a windfall for Shahar Solutions. “Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have some of the highest CO2 emissions per capita in the world. They need our technology.”

As a social entrepreneur and wide-eyed oleh, Wiesel also hopes that the mini-idyll of peace that Shahar Solutions intends to create will add to the company’s appeal, no matter what the American election brings.

“I really feel strongly,” he said, “no matter who the U.S. president is, that the momentum towards peace has already started and needs to continue.”

Orit Arfa is a journalist and author based in Berlin.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.