LEEDS, England (JTA)—In early December, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown did something very rare for a European leader: He publicly pointed his finger at a Muslim country and told it to get its act together.

“Three quarters of the most serious terrorist plots investigated by U.K. authorities are linked to al-Qaida sympathizers in Pakistan,” Brown said after meeting Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari shortly after last November’s terrorist attacks in Mumbai, India, which were carried out by a Pakistan-based terrorist group.

Brown’s remark highlighted his government’s ongoing frustration over Britain’s position as Europe’s top host of Islamic radicals.

British intelligence services estimated in 2007 that 2,000 potentially violent Islamic extremists reside in Britain, up from 1,600 in 2006.

The government and some Muslim groups are trying to counter the threat of extremism in two primary ways: tougher law enforcement and implementing an unprecedented number of “de-radicalization” programs. It will be years, if not decades, before their success can be measured with any accuracy.

In the meantime, Britain has its work cut out. A 2008 survey by the market research agency YouGov found that 32 percent of British Muslim university students believe killing is justifiable either “to preserve and promote” religion or “if that religion was under attack.”

Another survey of British Muslims, by Populus in 2007, found that 13 percent of Muslims aged 16 to 24 “admire organizations like al-Qaida that are prepared to fight the West.” The survey also found that 37 percent of Muslims in that age group say they would prefer to live under Islamic law rather than British law.

Two major factors have helped make Britain a hotbed of radical Islam, terrorism experts say: the country’s tolerance of foreign-born extremist clerics up until a few years ago, and the fact that most British Muslims have roots in Pakistan, where al-Qaida and other radical groups have a strong presence.

Some Muslims in Britain who go back to Pakistan to visit family forge and maintain connections with radical Islamic outfits, according to Lorenzo Vidino, a fellow at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University who has written extensively about al-Qaida.

Mohammed Siddique Khan, the ringleader of the July 7, 2005 London bombings, trained at al-Qaida-type camps in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border area. The British security service, MI5, says it monitors an average of 30 serious terrorist plots in Britain at any given time, with the vast majority tied to Pakistani groups.

It wasn’t until the 2005 London transit bombings, which killed 52 and injured hundreds, that Britain began cracking down on Islamic hate-mongering in the country. Before then, Britain had failed to implement the kind of tough anti-terrorism laws in use across the channel, in France, where mosques were under police surveillance and suspects could be jailed for up to three and a half years on the vague charge of “association with a terrorist” while prosecutors gathered more evidence.

The most important step was the passage of laws allowing authorities to deport foreign nationals for expressing support for terrorism, enabling Britain to clear out some radical imams. In 2006, the scope of activities constituting support for terrorism was expanded, so that those who published or disseminated publications approving of terrorism, or spent time abroad at terrorist training camps, could be prosecuted. New laws also enabled authorities to hold terrorism suspects for 28 days without charging them and limit the movement of terrorism suspects.

“Intelligence agencies have more capabilities now, more Arab-speaking members of services, tougher anti-terrorism laws,” said Jonathan Laurence, the author of two books on Muslims in Europe and a professor at Boston College.

Law enforcement is only part of Britain’s effort to reduce the threat of terrorism on its own soil.

Last July, the British government unveiled an $18 million de-radicalization program aimed at tackling Islamist extremism at the local level. The program, which has the support of moderate British Muslim organizations, encourages local town councils to support Muslim organizations that counter radical activity.

The London-based Quilliam Foundation, which was founded by former members of the radical Islamic organization Hizb ut-Tahrir (Party of Liberation), known by the acronym HT, is one part of that effort. The foundation is notable because it is the only de-radicalization group in Britain run by former radicals, and may be the only one of its kind in all of Europe.

Quilliam promotes a version of Islam that is compatible with Western democratic values and rejects the notion promoted by groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood and al-Qaida, which say Muslims must create a state governed by Islamic law, or Shariah, wherever they live.

In many respects, Quilliam practices a form of cult prevention: In this case, the cult is a political ideology that distorts the Islamic faith.

Ishtiaq Hussain, a former member of HT, says the way to woo Muslims away from extremists is to publicly demonstrate that radical Islamist interpretations of the Koran are incorrect. “For instance, they put forth that there was a single Muslim caliphate at the time of the Ottoman Empire that should be revived, when no such entity existed,” Hussain said of HT.

Hussain, whose parents were middle-class Pakistani-born Britons, fell out with his very tight circle of HT comrades after going abroad to visit Muslim countries in the Middle East.

“I was in these countries and asking people when they would rise up and form the caliphate,” he said. “They would look at me and say, ‘We don’t care about an Islamic super-state. We just want to get on with our lives.’ “

When Hussain challenged HT leaders with questions upon his return, he never received clear answers, he said.

Supported by government and private funds, Quilliam teaches police, parents and teachers how to debunk HT rhetoric. The foundation sends reformed HT members to schools and mosques to help promote a message of tolerance. They also help imams counter radicalism among their congregants.

Most imams in Britain, Hussain said, “are from the Indian subcontinent and are trained to teach the memorization of the Koran, not deal with radical extremism among British-born Muslim youth.

“There is a generation gap and a cultural gap,” he said.

A leading scholar on Muslims in Europe, Olivier Roy, who is a research director at the French National Center for Scientific Research, says Muslim communities often are too poor to pay for British-born imams who might make the mosque a place to woo young British Muslims away from the temptations of extremism, drug use and gangs—problems with which British Pakistani parents say their children struggle.

“All imams need to be teaching that Britishness and Islam are not in conflict, but some of them can’t even speak English,” said Ishtiaq Ahmed, who has created a training program in Bradford for mosques to promote the idea that Islam is compatible with being a law-abiding British citizen. The program, Nasiha (

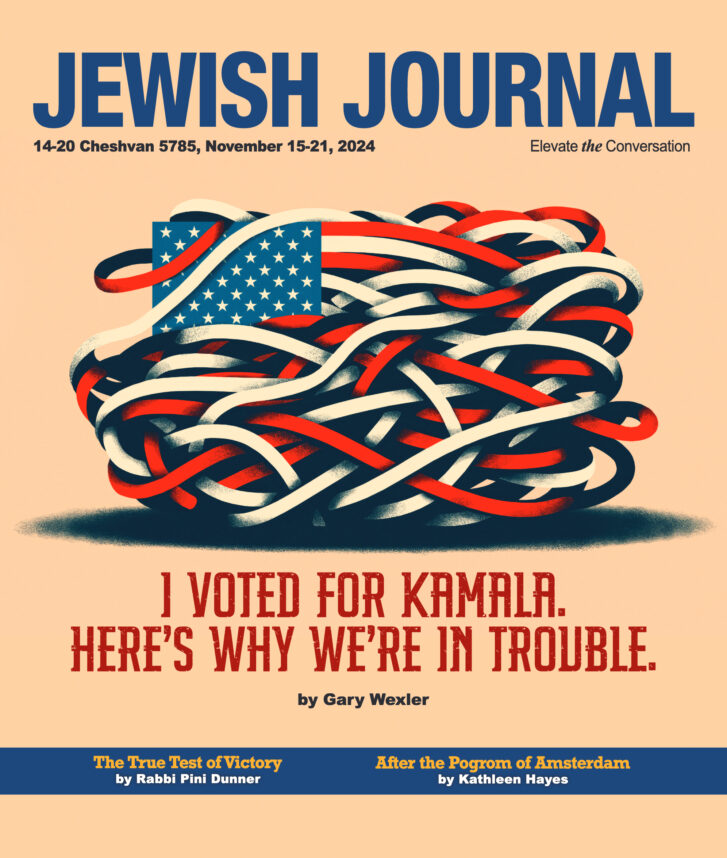

Did you enjoy this article?

You'll love our roundtable.

Editor's Picks

What Ever Happened to the LA Times?

Who Are the Jews On Joe Biden’s Cabinet?

No Labels: The Group Fighting for the Political Center

Latest Articles

Life in the Shadow of the Akedah

Things Done on Highway 61 – Thoughts on Torah Portion Vayeira

Life’s Roadblocks Are a Blessing

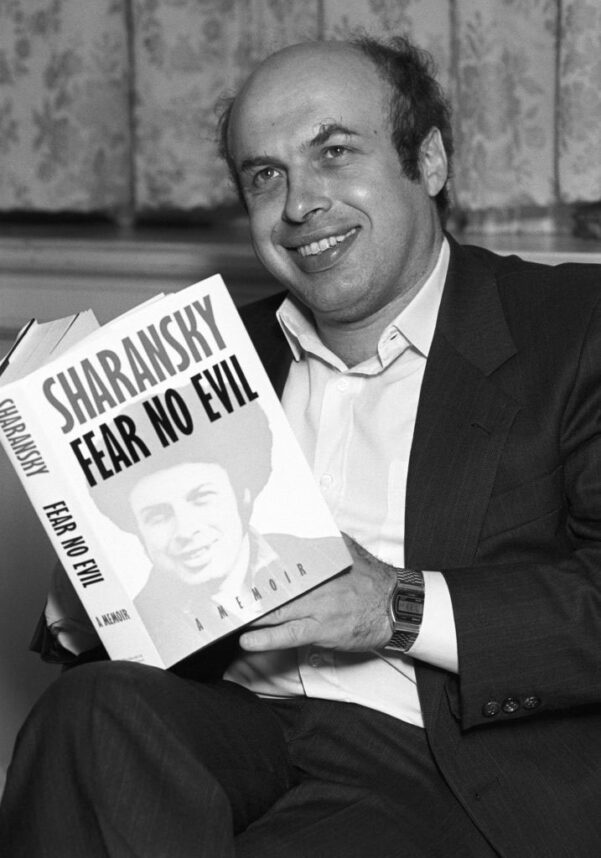

Natan Sharansky Then and Now

A Moment in Time: “We Don’t Visit Israel. We RETURN to Israel”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.