A gleaming Indian Scout 101 motorcycle, vintage 1929, helped kick-start the first Maccabiah Games in Palestine and with it much of Jewish sports history in the past 87 years.

Fast forward to the 20th Maccabiah this past summer, when an identical motorcycle was installed in the entrance hall of the Maccabi Sports Museum in Ramat Gan, Israel, and became an instant favorite of camera-toting tourists.

The two motorcycles link two vastly different times: one when a “Jewish Olympics” was thought to be an impossible pipedream, and this year’s event that brought 10,000 Jewish athletes to Israel.

To commemorate the games’ origins, planners of the 2017 Maccabiah wanted to display the type of motorcycle ridden across the Middle East and Europe to let Diaspora Jews know that the first such sporting event was to be held in 1932. Present-day officials were not sure any of those antique bikes could be found.

But after a two-year search, a motorcycle that fit the bill was located in the garage of a Norwegian collector and bought for 24,500 euros ($28,665) in 2016. With added costs for shipping and inspection and the hefty Israeli customs fee, the total cost came to 61,000 euros, then equal to $71,370.

To raise the funds, Eyal Tiberger, executive director of the Maccabi World Union, turned to Steve Soboroff, an influential figure in the Los Angeles business and civic world and president of the L.A. Board of Police Commissioners.

In the run-up to the previous Maccabiah Games in 2013, Soboroff had organized a committee of 18 well-heeled Los Angeles donors to enable Jewish athletes from poorer Diaspora communities to participate.

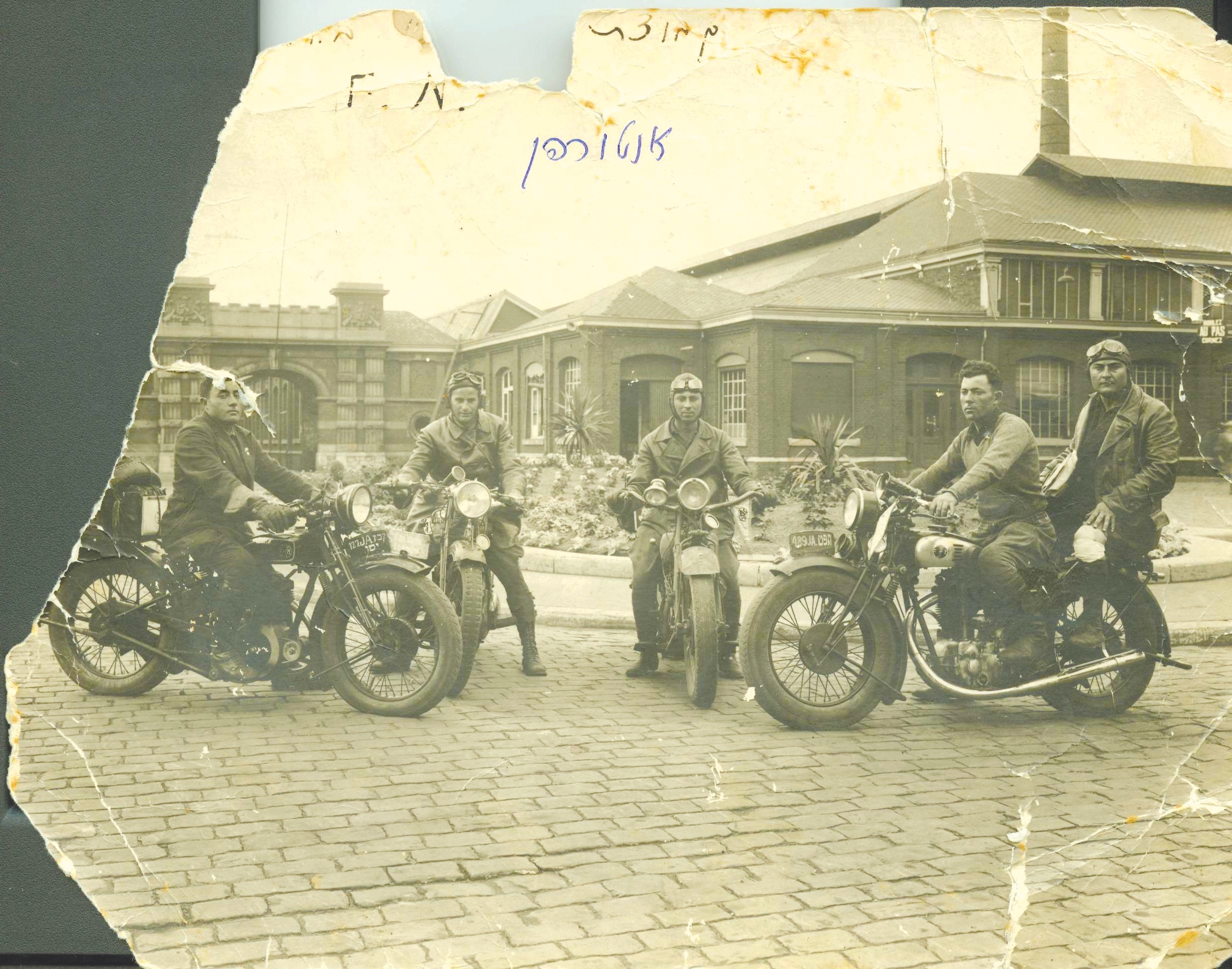

The 11 Motosikiliztim were hailed by ecstatic Jewish crowds.

He was joined for the 2017 Maccabiah support drive by Steve Lebowitz, president of a Santa Monica real estate firm dealing in hospitals and other health-care related buildings, and his son David Lebowitz, the firm’s executive vice president.

The latter, a one-time golf pro, was a mainstay of the U.S. golf team at the 2017 Maccabiah, placing fourth in the individual competition, while his team came in second after losing a tiebreaker to the winning Israeli team.

“At 42, I was about 12 years older than the next oldest man among some 85 golf competitors from a dozen countries,” David Lebowitz said. “The other players called me ‘uncle’.”

Also contributing to the Maccabiah’s financial support was Daniel Gottlieb, a former partner of the elder Lebowitz.

They were all inspired by the beginning of the Maccabiah saga, in 1929, when Yosef Yekutieli, a Palestinian (in those days, the Jewish inhabitants of the land defined themselves as “Palestinians”), presented the idea of a quadrennial “Jewish Olympics” to the Maccabi World Congress meeting in Prague. There were a few outspoken skeptics — with good reasons.

For one, in all of British-run Palestine there was not a single stadium, swimming pool or running track. For another, the British foreign office worried about the entry of “illegal” Zionist immigrants, would likely veto the whole idea. Add to such factors the 1929 worldwide Depression and large-scale Arab massacres of Jews in Palestine, and the question was whether Jews in the Diaspora would participate in the games.

Even if all these obstacles were overcome, how would Jewish communities in the countries of the Diaspora be informed and mobilized to send teams. (Remember, this was before the internet, television, cell phones, international radio broadcasts and easy international telephoning.)

Fortunately, Yekutieli came up with a publicity stunt worthy of a Madison Avenue genius. With the help of his friends, he rounded up 11 motorcycle riders — dubbed “The Motosikiliztim” in a merger of Yiddish and Hebrew — to speed the glad tidings of the planned Maccabiah among the major Jewish communities of Europe.

Their route of some 3,000 miles started in Tel Aviv, went to Haifa and Lebanon, and then, after a boat trip to Turkey, stopped at big cities and Jewish communities in Romania, Czechoslovakia, Ukraine, Poland, Germany, Austria, France and Belgium. That trip would have been forbidding at any time, but more so in the days before interurban highways, observed Rodney Sanders, Tiberger’s right-hand man.

The 11 Motosikiliztim were hailed by ecstatic Jewish crowds, feted in the press, and hailed by civic and national leaders — in countries not necessarily known for their philo-Semitic sentiments — as reincarnations of the biblical Maccabees.

Some burnished their heroic reputations through an incident reported on Aug. 1, 1930, by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) and headlined “Palestine Maccabeans Rescue 36 from Drowning in Germany.”

As JTA reported, four of the motorcyclists on the return leg of their mission approached a bridge spanning Germany’s Ilme River and saw that a tour bus with 36 passengers had plunged off the Ilme Bridge into the river. “Hastily dismounting from their motorcycles,” the JTA report said, “the four Maccabeans, fully clothed, plunged into the river and saved 36 passengers who were struggling in the waters.”

Most of the motorcyclists participating in the initial 1930 mission rode Belgian-made Sarolea machines, but a second ride in 1931 included the now-famous Indian 101 Scout.

Those first games in 1932 attracted 390 athletes from 27 countries. The event has grown so much over the decades that 10,000 athletes came from 85 nations this year.

Planners of the 2017 games wanted a motorcycle of the same type and year as used by the original Motosikiliztim. Tiberger commissioned Sanders to lead the search. Sanders, in turn, hired Bas Van Duinkerken, an expert Dutch restorer of antique and vintage motorcycles. On the verge of abandoning the mission, Van Duinkerken found a 1928 Indian Scout 101 in Norway and brought it to Israel in triumph. It is now the oldest motorcycle in Israel and probably in the entire Middle East, Sanders said.

Rare footage of the earliest Maccabiahs and the ride of the Motosikiliztim is included in the film and the shorter television special “Back to Berlin,” which British producer Catherine Lurie-Alt expects to release next spring.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.