When Stephen Miller began to crop up in headlines last spring as a member of then-candidate Donald Trump’s inner circle, those who knew him as the scion of a Jewish household in Santa Monica were intrigued — but for the most part unsurprised.

As far back as Hebrew school, his classmates pegged him as a young contrarian. Some now suggest that his journey as an impassioned evangelist for the right, which eventually landed him a West Wing office, began as a rebellion against Santa Monica’s bleeding heart, multiculturalist and heavily Jewish left.

News reports identify Miller, 31, as a principal author of Trump’s draconian immigration measures, including the executive order the president signed in late January targeting immigrants from Muslim-majority countries. These politics are generally reviled in the liberal circles of his Jewish upbringing — such as at Beth Shir Shalom, where he went to Hebrew school, and which describes itself online as a “Progressive Reform Synagogue,” and at The Santa Monica Synagogue, a Reform temple where he was confirmed in 10th grade.

At The Santa Monica Synagogue, members skew liberal, especially when it comes to immigration, said Rabbi Jeffrey Marx, the temple’s longtime rabbi. The confirmation course itself — taught by Marx once a week on Tuesday evenings — sought to instill empathy and respect for the other, the rabbi said.

“We certainly did our best here to teach him the ethical standards of Judaism,” Marx said. “He certainly didn’t grow up not having that knowledge base.”

Miller, who now holds the title of senior policy adviser to the president, first gained nationwide attention as the hype man who would pump up audiences before Trump’s appearances at campaign events. His national profile peaked during a Feb. 12 round of the Sunday talk shows, where he struck an authoritarian note that rankled many liberal West Coasters.

“The powers of the president to protect our country are very substantial and will not be questioned,” he told John Dickerson of “Face the Nation” on CBS, discussing the president’s first abortive attempt at a travel ban.

Long before that, though, Miller was the middle child in a Jewish real estate family with immigrant roots, and far more interested in “Star Trek” than politics.

His mother, Miriam, who came to Los Angeles as a social worker, grew up in the well-to-do Glosser family of New Deal Democrats in Johnstown, Pa. Her grandparents were Eastern European immigrants. Stephen’s father, Michael, is a Stanford-trained lawyer who pivoted into real estate management. Peers described the elder Miller as a Jewish community leader, who served in board posts for a number of philanthropic organizations, including on the national board of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC-JIR) and the board of directors of The Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles. Together the couple owns and operates a real estate investment company that controls 2,500 residential units from Pico Rivera to Valley Village.

The Millers also have given generously over the years: From 2013 to 2014, the family donated $25,000 to the American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science, a research university south of Tel Aviv, tax documents show. Other recipients of their largesse include the Republican Jewish Coalition and Stanford Law School.

Repeated requests for interviews with Stephen Miller and his parents went unanswered.

Over the years, the family appears to have moved from temple to temple, spending time at The Santa Monica Synagogue, also known has Sha’arei Am, Beth Shir Shalom and Kehillat Ma’arav, a Conservative shul near the 10 Freeway. Each congregation is notable for the liberal politics of its members — but Michael Miller was different.

Steven Windmueller, professor emeritus at HUC-JIR, has known Miller since both men were involved with the now-defunct L.A. Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC), where Windmueller was director and Michael Miller co-chaired the Western Region, which included Santa Monica and much of the Westside. Windmueller said Miller was “rather conservative in his political outlook” and not particularly shy about it.

But even those who differ from him politically described Michael Miller as a mensch. “He was a great guy to work with,” said Michael Hirschfeld, who took over the directorship of the JCRC after Windmueller left in 1995. “He was committed, he was loyal, he was respectful — he was an all-around good guy.”

Early on, young Stephen Miller veered away from the progressive ethos of the temples where he grew up.

Even in Hebrew school at Beth Shir Shalom, Miller was something of a budding provocateur, according to a classmate who asked not to be named so he could speak freely. Though he wasn’t the full-blown contrarian he would become in high school, Miller seemed to enjoy getting a rise out of people, the classmate recalled.

“He was not very concerned with being well liked,” he said.

Another Hebrew school classmate, Sophie Goldstein, said classes encouraged debate — an area where Miller thrived — over Torah tractates and other aspects of the religion.

Once, Goldstein said, the class of about seven or eight kids was discussing how to deal fairly with the sole remaining slice of a pizza pie, when Miller decided to end the debate.

“We’re all talking and talking about it. In the middle of this discussion, Stephen slaps his open hand down on the middle of the slice of pizza,” she recalled. “And of course nobody would touch this pizza slice after he put his greasy 13-year-old paw on it.”

But at that time, politics were on the far backburner for Miller, according to those who knew him. Jason Islas, now a Santa Monica-based journalist, bonded with Miller as a preteen over their shared Trekkie inclinations. Islas said throughout their time together at Lincoln Middle School, world events were far less important for Miller than, for instance, his obsession with Capt. Kirk.

Then, in the early 1990s, the real estate market soured and the Millers downsized from a house on a tree-lined street in the well-to-do neighborhood north of Montana Avenue to a somewhat smaller one in a less affluent area of Santa Monica, off a busy stretch of Pico Boulevard.

The move came just before Stephen entered high school. Islas recalls Miller breaking off the friendship around that time — because, as he says Miller told him, Islas is Latino.

Soon, Miller developed a reputation as a rabble-rouser at Santa Monica High School. He rallied against what he saw as rampant anti-Americanism, decried Spanish-language bulletins, lobbied hard for daily recitations of the Pledge of Allegiance and fought to bring conservative speakers to the overwhelmingly liberal school. A video from the time shows him getting booed offstage during a student government campaign speech, wearing a self-assured grin, for suggesting students shouldn’t have to clean up after themselves since janitors are paid to do so.

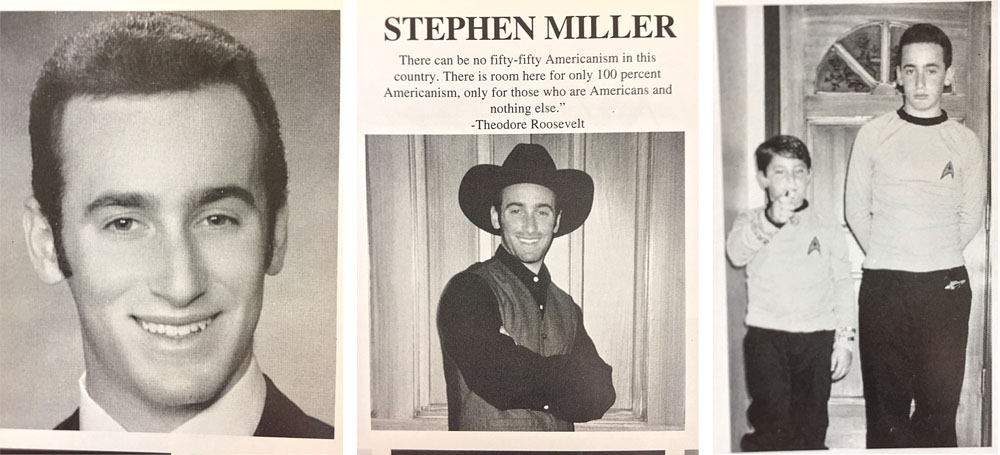

Since then, Miller has often defined his ideology in opposition to what he has called the “racial left.” In his high school yearbook, he quotes President Theodore Roosevelt: “There can be no fifty-fifty Americanism in this country.”

“He thought of himself as an anti-establishment figure in an area where the establishment was very progressive on economic and ethnic and racial diversity,” Islas said of Miller’s upbringing.

“We certainly did our best here to teach him the ethical standards of Judaism. He certainly didn’t grow up not having that knowledge base.” — Rabbi Jeffrey Marx, The Santa Monica Synagogue

Islas speculated that Miller’s ideology had its roots in a “teenage rebellion” against his liberal surroundings.

“This is a particular strand of conservatism that can only be created in a place where the predominant paradigm is wealthy, liberal identity politics,” he said.

Miller has said as much in interviews with the media.

“When we think of nonconformity, we tend to imagine kids in the ’60s rebelling against ‘the system,’ ” he told the Los Angeles Times in January. “This was my system. My establishment was a dogmatic educational system that often uniformly expressed a single point of view.”

Among Miller’s battles with the administration at Santa Monica High School was his fight to bring conservative author David Horowitz, founder of the Sherman Oaks-based David Horowitz Freedom Center, to speak on campus.

Administrators at first denied Miller’s request, but later gave in. After his speech, Horowitz stayed in touch with the young man, who came to see him as a mentor. Horowitz credited the teen with a great deal of chutzpah for standing up to hostile teachers and administrators.

“I even thought at the time, ‘This is a very bright young man, but how’s he going to get recommendations for college out of these people?’ ” Horowitz told the Journal in a phone interview.

The two men share more than their conservative ideas and distaste for liberal identity politics. Both strayed far from the political norms in their hometowns.

Horowitz, 78, grew up in a communist family in a hardscrabble neighborhood of Queens, where the Jewish community held President Franklin Roosevelt to be as sacred as any sage rabbi. He said his background growing up among leftists shaped his particular brand of politics, and he suspects the same is true for Miller.

Whereas conservatives tend to approach politics pragmatically, liberals bring a certain missionary zeal, he said. When the liberal political style is applied to conservative ideas, you get somebody like Miller.

“You learn a certain style of politics when you’re on the left, and if you take it over into the right, it comes out as hardball,” Horowitz said.

He also speculated that Miller’s experience dealing with the ire of his classmates inoculated him early on to the hectoring of political opponents who might name him a racist or a xenophobe. And indeed, by the beginning of his senior year at Duke University, Miller would recall with nonchalance being labeled a racist, writing in the school paper that “my skin, in addition to being somewhat pasty, is also very thick.”

“Once you break with the left, they want to kill you,” Horowitz said. “So you learn to survive.”

By the time Miller arrived in Johnstown, Pa., for a campaign event just 18 days before the presidential election and mounted the stage to the sound of a thrumming bass and fast-paced rock-’n’-roll drumbeat, his act was smooth, well practiced. He beamed at the audience, wearing a gray suit, skinny tie and pocket square.

From Duke, Miller had landed jobs with various Republican politicians, such as Michele Bachmann of Minnesota and David Brat of Virginia. He’d worked with Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama, now the attorney general, to defeat the bipartisan Gang of Eight immigration reform bill in 2014.

In Johnstown, looking the part of the Washington operative he had by then become, he would nonetheless rail against the government elite, singling out Trump as the last beacon of hope for working-class Americans.

But this campaign stop was somewhat different from the dozens that preceded it. Miller’s mother grew up here during a better time, before Bethlehem Steel, the town’s major employer, went under.

The Glossers first arrived in Johnstown at the turn of the 20th century after fleeing Cossacks and conscription in Antopol, Belarus. As the family established itself, more relatives moved in, until they were a sizable contingent of the town’s population. The Glosser Brothers tailoring shop became Glosser Brothers Department Store on Main Street, and the family thrived. Stephen’s grandfather, Isadore “Izzy” Glosser, was an executive in the family business, serving also as president of Beth Sholom Congregation, the town’s only synagogue. As a kid, young Stephen would travel to the town of some 20,000 each summer to visit his grandparents.

“Johnstown, to me, represents, if you look at the history of this amazing place, what is possible for America when our government, as it once did, puts the American people first,” he told the enthusiastic crowd.

What he failed to mention was that the entire Johnstown wing of his family were Roosevelt stalwarts, New Deal Democrats almost to a man, according to Larry Glosser, a cousin of Miriam Miller.

“I found it strange when I heard that he was Miriam’s son,” Glosser said in an interview with the Journal.

Other than one of his younger brothers, Glosser doesn’t know of anybody in his family who shares Miller’s conservative leanings.

“How would you like it if a family member became the face of white nativism in this country?” Glosser said. “I’m glad he doesn’t have my last name.”

Glosser said he eventually grew apart from Miriam, and doesn’t have any distinct memory of meeting Stephen at all. Discovering his cousin’s name in the news has led to some puzzlement among the extended Glosser clan, in private conversations and on Facebook.

“With all familial affection I wish Stephen career success and personal happiness, however I cannot endorse his political preferences,” Miller’s uncle, David Glosser, wrote in a public post that criticized Trump’s rhetoric.

And while others who knew him in his Santa Monica days found Miller’s new role strange, it also seemed somehow fitting. The Hebrew school classmate who preferred to remain anonymous said he first recalls hearing about Miller’s ascendancy on Facebook.

“I was like, ‘Whoa, Stephen is, like, writing Trump’s speeches,’ ” he said. “That’s crazy — but totally unsurprising.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.