It’s not surprising that irreverent Jewish comedian Sarah Silverman has a sister who knows how to work a crowd. But finding out her sister is a Reform rabbi, author, activist and mother of five living in Jerusalem might give some pause.

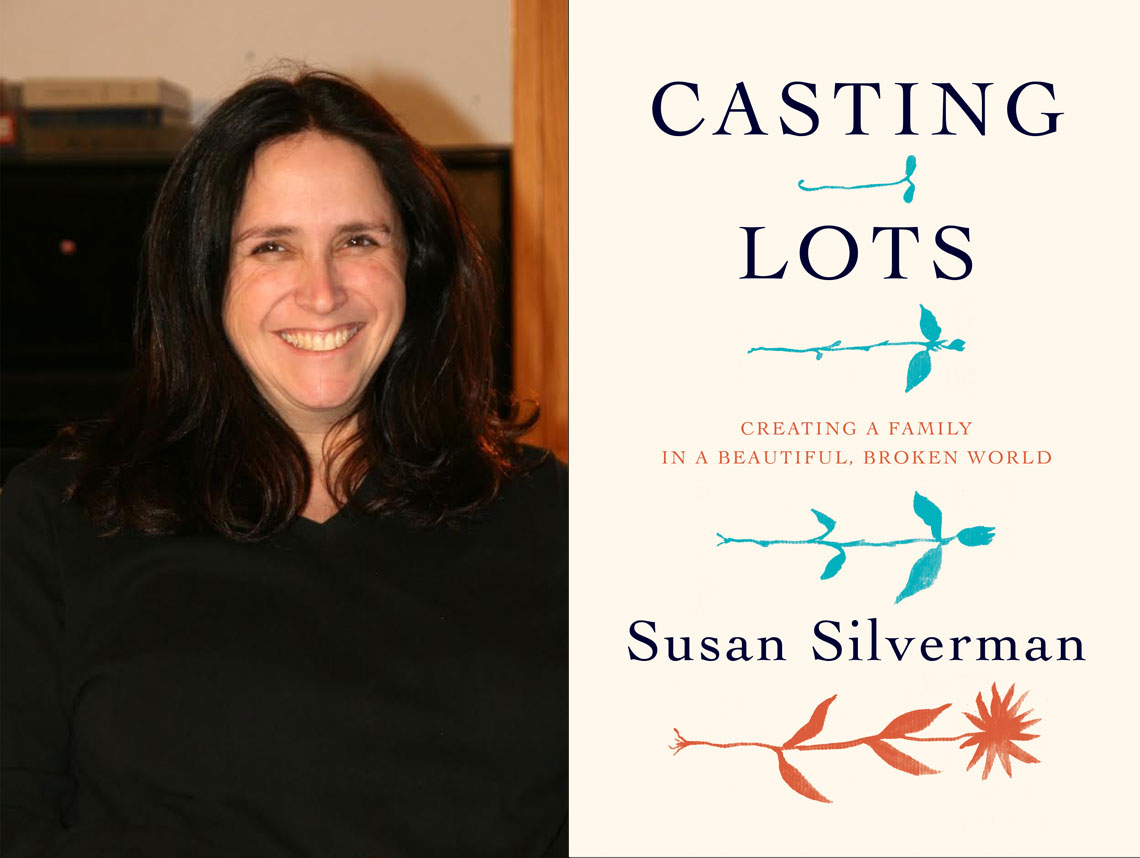

During a recent appearance at American Jewish University (AJU), Susan Silverman, the oldest of four sisters, mixed jokes with poignancy in discussing her book “Casting Lots: Creating a Family in a Beautiful, Broken World.” The book has drawn praise from actresses such as Mayim Bialik and Nia Vardalos, and authors such as “Jewish Literacy” scribe Rabbi Joseph Telushkin.

Silverman’s memoir focuses on her early years growing up secular with Christmas trees in the family’s suburban Massachusetts home, her unlikely path to ordination, and the ups and downs of fulfilling her childhood dream to adopt children.

Silverman and her husband — Yosef Abramowitz, CEO of Arava Power and one of the world’s foremost green-energy pioneers — live in Jerusalem with their three daughters by birth and two Ethiopian-born sons they adopted, all of whom range in age from 12 to 22.

For the event at AJU’s Burton Sperber Community Library, called “Coffee & Conversation,” Silverman talked with Jewish Journal columnist Danielle Berrin as an intimate crowd of a few dozen people on folding chairs sipped coffee.

“My husband always jokes that I never asked him about adopting kids,” Silverman said. “He always says, ‘You just brought home paperwork.’ ”

Silverman offered her best guess as to why she always had such an “unusual dream.” During her youth, Silverman’s parents took in foster children for temporary stints. One incident in which Silverman had to say goodbye to a foster child, a girl who stayed with the Silvermans for a few years and came to feel like an older sister, left an indelible impression.

“I remember waving goodbye to her,” she said. “She had three matching suitcases we got her as a gift to pack her stuff. I just remember waving and thinking what a weird gift: matching luggage. I couldn’t believe some people didn’t have families. That felt wrong.”

In 1999, after an exhaustive process of paperwork, interviews and waiting, Silverman flew to Addis Ababa to pick up her first adopted son, Adar, from an orphanage. Attendees at the event watched a moving video documenting the experience of getting Adar and bringing him home to meet his two older sisters and the rest of his new extended family. Afterward, Silverman addressed why she and her husband had settled on Ethiopia as an adoption site.

“Ethiopia was because we wanted to adopt from a country that had a natural Jewish connection. It didn’t matter if the kids were Jewish but we wanted something we could weave into our lives as Jews. So, it came down to Russia and Ethiopia — and we didn’t want to raise our kid as an anti-Semite — so we thought maybe we should go with Ethiopia,” she said to laughter. “Also my husband did a lot of work bringing Ethiopian Jews to Israel. It was really an instinctive draw.”

Silverman also showed photos of her multiracial family and answered questions about potential racism the family has had to deal with in Israel.

“Someone once asked if we were a camp,” she said of an experience here in the United States. “But no, no one in Israel is surprised to see an Ethiopian Jew. It’s not an issue.”

As a rabbi and lover of Jewish texts, Silverman believes adoption has a special place in Judaism. She referred to the bible, pointing out that many titanic Jewish figures are the result of adoption.

“Many of our Jewish heroes are adopted,” she said. “Moses was part of the first open adoption. Mordechai adopted Esther of the Purim story. Ruth was adopted by Naomi. Many major redemptive figures were adopted. It’s kind of amazing.”

“Casting Lots,” Silverman said, was written partly as an advocacy project to help raise the profile of her organization Second Nurture, which aims to support adoptive parents. Essentially a community organizing initiative, Second Nurture tries to make communities more adoption friendly by creating supportive factions that can address universal difficulties of raising children from troubled circumstances and by helping prospective adoptive parents navigate bureaucratic barriers in the adoption process.

“We need cohorts in communities, made up of experienced parents, social workers and other experts who are going to hold your hand so you’re not doing it alone,” she told the Journal. “We don’t want people to feel like they’re reinventing the wheel. You will have the support of other adoptive families and from the community. We are going to help communities reinvent themselves to reincorporate adoption as a part of the community.”

Silverman’s book tour included stops along the East Coast, Northern California and Canada. While in Los Angeles, she said she took time to meet with Jewish community leaders and rabbis to promote Second Nurture. So far, Silverman is cultivating her Jewish connections to promote her organization’s efforts in synagogues and other Jewish communities. She said she’d like to establish “second nurture communities” in collaboration with churches and other faith-based communities, telling the Journal, “We don’t care about whether or not they’re Jewish, just communities of good people.”

When Berrin implored Silverman to give her pitch for adoptive parents, she quipped that she had an “elevator pitch” at the ready for “floors seven to eleven” in case she ever runs into potential donors.

“There are 400,000 kids in the foster care system in the United States,” she said as the room fell silent. “One hundred and seventeen thousand of those kids are available for adoption right now. Kids who grow up in foster care are twice as likely to have PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) as war veterans. Internationally, there are between 8 and 12 million kids in institutions. Kids are generally released from orphanages, usually on a specific day. Every few months there’s a release. There are pimps waiting on the street outside. And these girls go with them because they have no place else to go.

“Can you imagine my 15-year-old being released, deaf, into the streets of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, instead of being the excellent student award winner at his school, a runner and loved to the ends of the universe? It’s unthinkable.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.