The central theme of the High Holidays is teshuvah, a restorative process that brings us back to ourselves, to our families and friends, to our community, to humanity, to the natural world, to Torah, and to God. Teshuvah demonstrates the power of hope, that who we are today need not be who we become tomorrow.

Teshuvah is a step-by-step process of turning and re-engaging with our inclinations, the yetzer hara-the evil urge that’s propelled by desire, lust, and self-centered needs and our yetzer tov-the good inclination that’s inspired by humility, gratitude, generosity, and kindness.

The beginning in the teshuvah process is, however, despair, hopelessness, and sadness, the feeling that we’re stuck and can’t change the nature, character, and direction our lives have taken us.

Judaism rejects pessimism, cynicism, and everything that impedes personal transformation and a hopeful future.

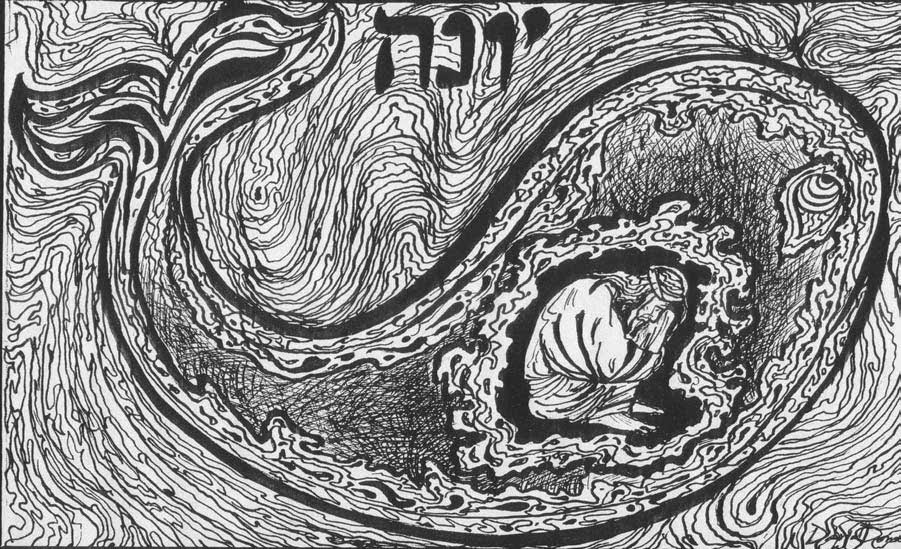

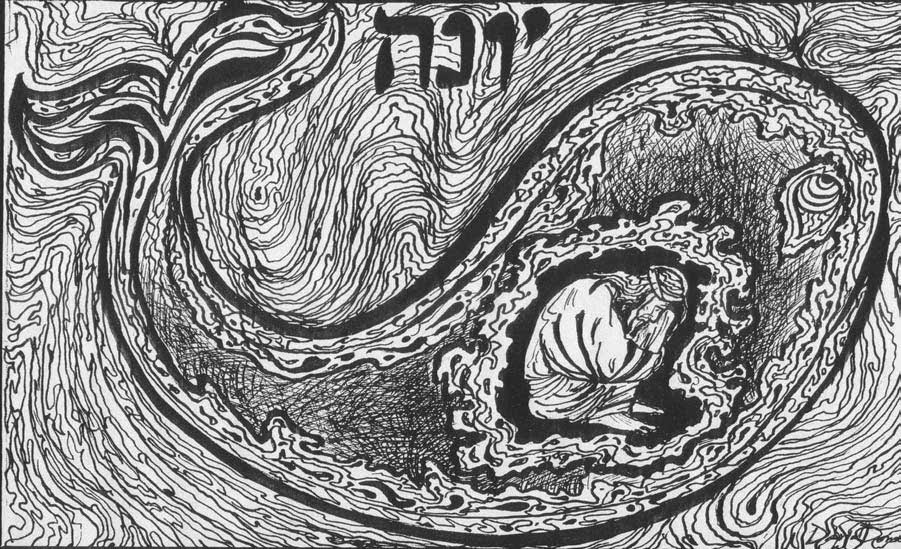

In the story of Jonah, to be read as the final scriptural portion on the afternoon of Yom Kippur, we read the tale of the prophet’s descent into despair and what’s required for him to change direction and restore a hopeful self.

Jonah is an unrealized prophet who runs away from himself, from civilization, and from God. Every verb used in his journey is the language of descent (yod-resh-daled). He flees down to the sea. He boards a ship and goes down into its dark interior. He lies down and falls into a deep sleep. He is thrown overboard down into the waters. A great fish swallows him and he finds himself down in its belly where he remains in utter darkness for three days and nights until his despair forces him, at last, to choose to live and not to die. Then he cries out to God to save him.

God responds and the great fish vomits Jonah out onto dry land. Jonah agrees this time to do God’s bidding and preach to the Ninevites to repent from their evil ways. The town’s people put on sack cloth and ashes and promise to change.

Jonah, however, still believes that change is impossible and the Ninevites are destined to failure. God chastises Jonah for his pessimism and lack of faith, for his self-centered concern for himself and not the well-being of others.

Teshuvah is difficult and challenging. It’s a dramatic break from the past, our refusal to remain stuck. It’s for the strong of mind, heart and soul, for those willing to work hard and transcend their suffering and fear of failure, to get up every time, to own without defense and excuse what we do and what we’ve become, to acknowledge all of it, to apologize to ourselves and to others without conditions that we’re responsible and at fault, and to recommit to our struggle step-by-step, patiently, one day at a time, one hour at a time, one moment at a time to turn our lives around.

When successful, teshuvah is restorative and utopian, for it enables us to return to our best selves, to the place of soul, to the garden of oneness.

Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik wrote that in teshuvah we’re able even to transcend time: “The future has overcome the past.”

Originally published – September 13, 2015

Originally published – September 13, 2015

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.