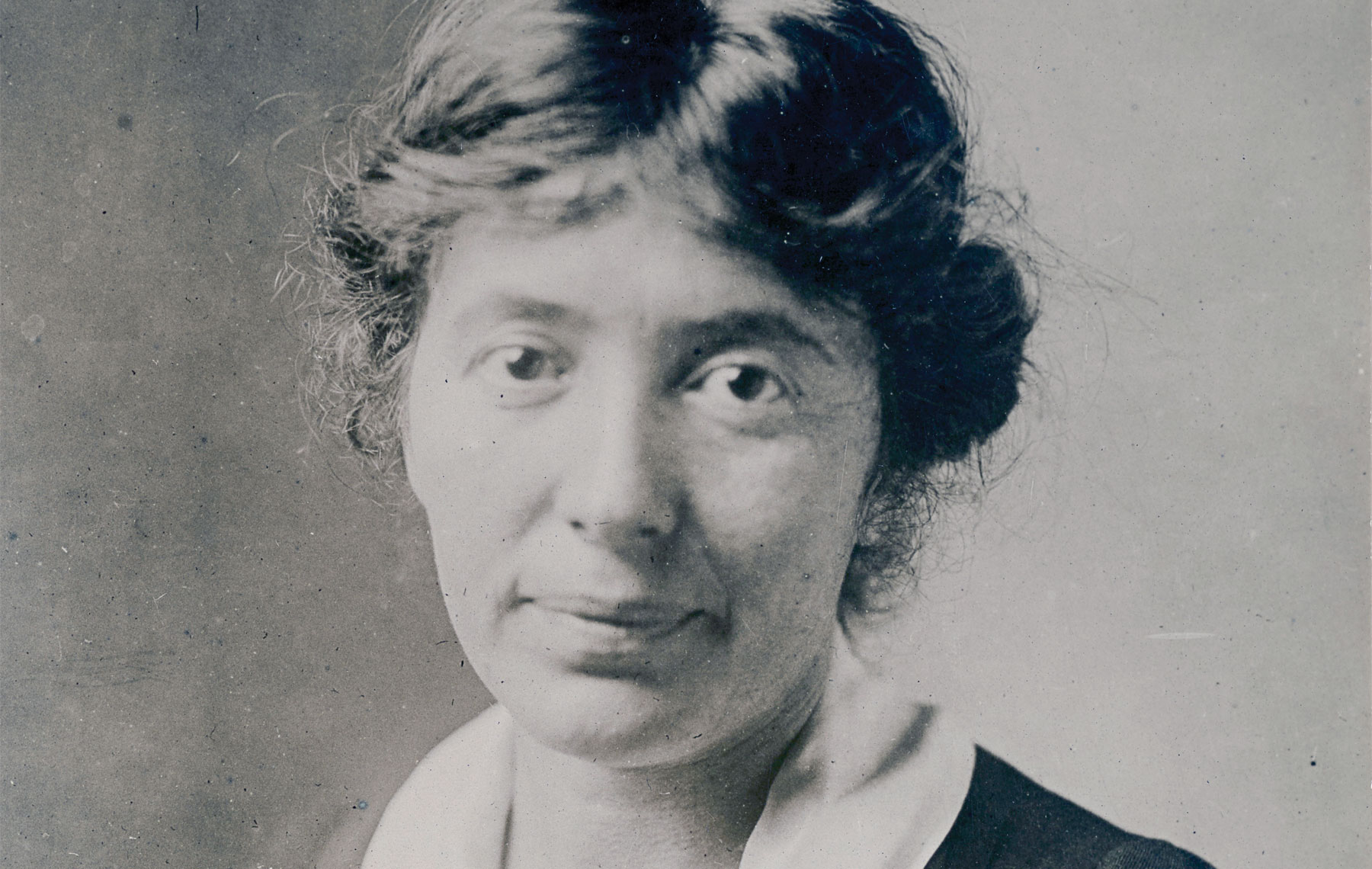

Rose Pastor Stokes was proudly defiant. President Woodrow Wilson tried to lock her up. The president told her to work for him, but she would not obey.

Disobedience came naturally to Rose Pastor Stokes.

She was the only child of an arranged marriage forced upon her mother. The reluctant Jewish bride’s parents physically dragged her, weeping, to the chuppah. The bride’s preferred choice was a gentile. In 1878, in a shtetl in the Russian Pale that had been forbidden. Instead, Papa chose a Jewish groom.

Rose (“Reisel”) was born the following year. But Rose’s father, the chosen hassan (groom), abandoned them before the girl turned 3. Mother and daughter fled to England, and then Cleveland, launching Rose’s lifelong journey beyond the Pale.

Her mother remarried and had six more children. Rose was a teenaged sweatshop worker in a Cleveland cigar factory when her stepfather abandoned the family. Twice, Rose had been abandoned by fathers. Twice, her poor mother had been abandoned by husbands. Female self-reliance was more than an ideal to Rose. It was a matter of survival.

In 1917, she was living in New York City, a 38-year-old successful journalist, playwright, poet, graphic artist and social critic. She fought for women’s suffrage, access to birth control, and the labor union movement. She believed in socialism and democracy. Today, she might call herself a Democratic Socialist. She supported the Zionist movement to create a Jewish nation, which she envisioned as a socialist haven. Had her life taken a different path, she might have become a kibbutznik.

The press called Rose a “Sweatshop Cinderella” when she married James Graham Phelps Stokes, the fabulously wealthy scion of gentile industrialists and philanthropists. Rose promised to love and honor, but not obey.

The couple worked together to uplift the downtrodden and dispossessed. They joined the Socialist Party, a curious choice for Graham, whose family had embraced capitalism and enjoyed bountiful wealth for centuries, beginning in colonial New England.

After the outbreak of World War I in Europe in August 1914, President Wilson struggled to avoid American involvement. He called for a “preparedness” campaign of “armed neutrality,” and then a policy of diplomacy for “peace without victory.” He campaigned for re-election in 1916 on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.”

He could not continue to keep us out of war. German submarine attacks on American and Allied Powers ships, plus the revelation that Germany tried to coax Mexico to declare war on the United States, became intolerable provocations. In April 1917, Wilson sent American troops to join the Allied Powers in combat.

“In only four months, Rose Pastor Stokes went from being invited to the White House to indicted for espionage.“

Wilson was determined to control public opinion. First, he formed the Committee on Public Information to create a marketing and propaganda campaign to boost support for the war.

Then he tried to silence criticism and dissent. At the president’s urging, the Espionage Act of 1917 was passed. Critics could be prosecuted and jailed for opinions that supposedly might discourage enlistment in the military or encourage American soldiers to desert.

The Socialist Party voted to oppose the president’s decision to enter the war. Rose and Graham Stokes resigned from the party and publicly announced their support for the war effort. She also resigned from the Woman’s Peace Party.

Rose insisted that she was not a pacifist. She was not a patriot. She was an internationalist. She would fight for America, even in the military if necessary.

Rose Pastor Stokes was aroused by Wilson’s quest to make the world safe for democracy, a worthy internationalist agenda. She revered democracy but despised capitalism, the system she blamed for the desperate plight of the poor. Wilson’s internationalism was of a different stripe. He wanted to create a League of Nations.

Wilson encouraged Rose to do more.

The director of Wilson’s Committee on Public Information’s Division of Films offered to make Rose Pastor Stokes a movie star.

The Division of Films was producing a movie in which “[w]e are going to show scenes of people who have been born in alien countries, who have become American citizens, and achieved places of worth and prominence. There will be two women in the picture.” The idea was to celebrate immigrants who supported the war effort, and to encourage others to do so. “We would like to have you enact one of the parts.”

Rose politely declined.

In November, Wilson’s daughter Margaret invited Rose to have dinner with her and the president at the White House to discuss other ways to help drum up support for the war.

Rose politely declined.

She recoiled from the “motley political elements” who applauded her initial pro-war stand. That same month, the Russian Bolshevik Revolution raised her hopes for a utopian international socialist movement. Those hopes would be dashed by the bloody Russian civil war and totalitarianism of the Soviet Union. But Rose could not predict all that.

She came to believe that Wilson’s war would not make the world safe for democracy, but it would promote what she viewed as rapacious capitalism. The results would enrich financier and banker J.P. Morgan and others whom she called war profiteers.

Rose recanted her support and turned against American involvement in the war.

Wilson had been against the war before being for it. Rose Pastor Stokes had been for the war before she was against it.

The government continued to pursue her. In January 1918, the Committee on Public Information’s Division of Publicity asked Rose to contribute something in writing for the pro-war propaganda campaign.

Rose politely declined, citing her “convictions regarding imperialism and freedom of speech.”

Rose Pastor Stokes returned to the lecture circuit, barnstorming the country and speaking about politics. She criticized the president for enriching war profiteers.

The Kansas City Star newspaper mistakenly reported that although Rose was “against” the war, she was “for” the U.S. government. She wrote to disabuse the editors of their misconception.

“I made no such statement, and I believe no such thing. No government which is for the profiteers can also be for the people, and I am for the people, while the government is for the profiteers.”

The newspaper published her letter, and the president had her arrested under the Espionage Act. He led the call to lock her up.

If she was not “for” the government, she must be “for” the enemies. That letter to the editor of a newspaper expressing her political opinions was enough to sustain a conviction and a 10-year prison sentence.

In only four months, Rose Pastor Stokes went from being invited to the White House to indicted for espionage. Just two months after she was asked to contribute pro-government propaganda, she was charged as a criminal who would be sentenced to a federal penitentiary.

The conviction was overturned on appeal in 1921, and the government declined to bring new charges. The war was over and Warren G. Harding had succeeded Wilson as president. Congress refused to endorse Wilson’s League of Nations. Rose Pastor Stokes divorced her wealthy husband in 1925, and at age 47, she married a 29-year-old, poor, Jewish, socialist scholar.

Alan Robert Ginsberg is a historian and the author of “The Salome Ensemble,” about four Jewish female immigrants who shaped American history in the early 20th century.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.