My mother and father are both in diapers. I wasn't at all prepared for this possibility. Dealing with the visual and olfactory aspect of my son's end products when he was a baby was an expected part of being a mom, but it's a completely different matter when it's my parents wearing the Pampers.

My mother was first. A few years ago, she was on a medication for dementia that instead of keeping her memory, loosened her bowels. Both my sister and I had the traumatic experience of being out in public with mom, hearing her gasp, rushing with her to the nearest restroom and then trying to figure out what to do.

It was demoralizing for my mother and very distressing for my sister and me. We learned to carry extra clothes and diaper wipes with us.

Fortunately, my sister and I both have rather sick senses of humor, and we could later laugh (albeit slightly hysterically) when sharing these nightmares with each other. My mother could even laugh about it, but it was colored by obvious pain about her aging and loss of control.

My mother is no longer on that medication and blissfully unaware (because of her dementia) of the fact that she wears diapers. Well, in fact, she actually does notice it, but forgets a few minutes later.

Mom lives in a board and care where, thankfully, someone other than me gets to handle her potty needs. I'm adjusting to the fact that my mother is old and child-like in many ways.

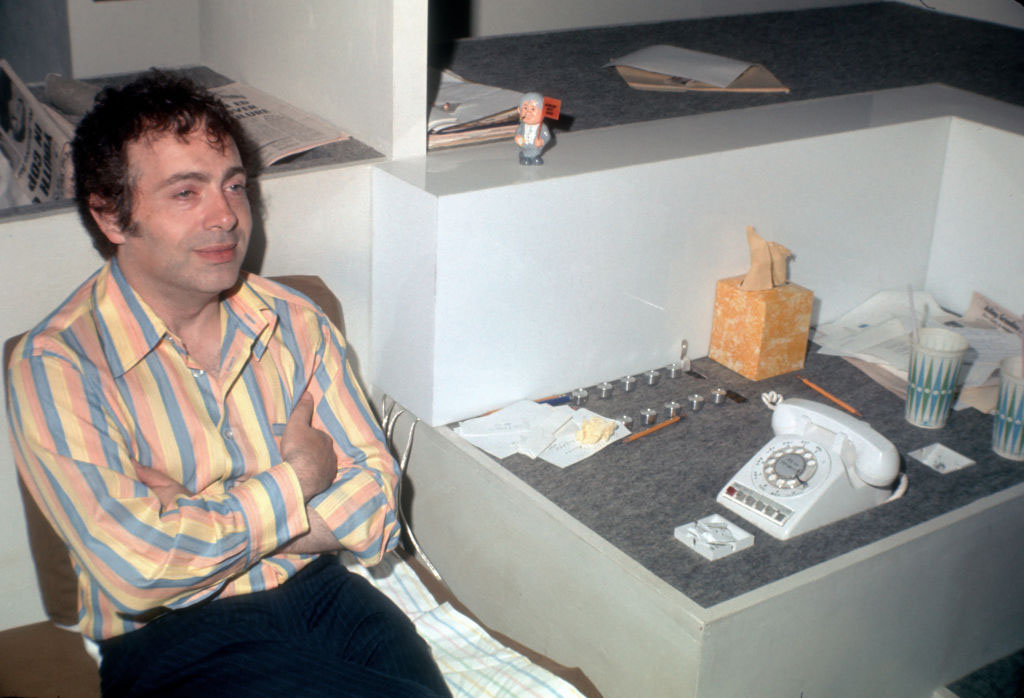

My 86-year-old father is still functioning fine mentally. He's still counseling clients and writing a book about handling fears. He's funny and together and basically still “my dad.”

But two years ago, a stroke left dad partially paralyzed on his right side. A fiercely independent man, this was a real blow to his pride and his view of himself. (The good news is that it forced him to stop driving, something we'd desperately wanted for years.)

After the stroke, dad was a prize student for the occupational and physical therapists, and he can now dress and feed himself, walk with a cane and even slowly type on his computer. He desperately wants to do everything for himself.

But the stroke left him with occasional loss of bowel control, and prostate problems have caused him incontinence. He wears pull-ups.

Dad hates it, and he is terribly frustrated and angry when he has an accident. I went to visit him in Ohio last August, and there was no doubt when an accident would occur, because dad announced it loudly, like a wounded or trapped animal. It was clearly horrible for him to be so powerless.

Much to my dismay, (yes, I confess, I was not thrilled) he often needed help with the clean up after such an accident. He would make his way into the bathroom, close the door, deal with the situation by himself and then he'd shout my name.

The first time I heard him yell, it sounded like panic, and I thought he'd hurt himself. I flew from the living room and threw open the bathroom door.

There he was, sitting on the thrown, his Depends around his ankles. My first thought was, “Oh good, he's OK.”

Then I felt irritated that I was being called to witness him in that state. Then came a childhood memory: dad, sitting on the can, his pants around his ankles, reading the entire Sunday Cleveland Plain Dealer, while my sister and I impatiently asked him when he was going to be done.

But this was different. We are now adults, and I haven't seen my father's rear end for about 48 years. Worse than that, he was ashamed and embarrassed at having to ask for help.

The circumstances during that visit brought up a lot of intense feelings about aging (both his and mine) and about mortality (both his and mine). And there was a deep sense of loss of the father I used to have — really until just a few years ago — who was vibrant, active and independent. We were both grieving.

One morning during my visit, I woke up with a full bladder and headed to the aforementioned one-and-only bathroom. The door was closed.

“Dad, are you in there?” (duh.)

“Hey, good morning sweetie. Don't worry, I won't be long!”

An hour later, he was still in there. Need I say, I was really uncomfortable. I looked in the garage for a pot of some sort. No luck.

Then I thought about squatting in the backyard, but there aren't fences between homes in this small Ohio town. So, I did what any desperate, agile person with a full bladder would do — I used the kitchen sink.

My father was still in the bathroom, so I called my sister. I described the entire scene, and we both had one of our “this-is-terrible-but-we-have-to-do-it-so-let's-find-it-amusing” giggles, which helped.

I have to admit that those first three days with my dad seemed like a month. I felt guilty that I couldn't wait to leave. For most of my life, I had my father on a pedestal.

He could fix anything — including personal problems. He skied and played tennis into his late 70s. He always had words of wisdom when I was in a crisis. He's still a sharp, vibrant man.

But since his stroke, it seems like he's shrinking in many ways. His ability to think of things beyond his physical challenges has diminished, which means a decrease in our usual stimulating, fun interactions.

However, after a few days, dad regained control of his bodily functions, and we did have a final day to talk before I returned to Los Angeles.

As often happens with people facing their later years, dad went back in time. He reminisced about his grandparents and his parents. He cried as he talked about how much his mother and father gave to others and how he admired them.

He recalled what a mensch his oldest brother was and what a bully his other brother was. He confessed to skinny-dipping with my mother before they were married. (Something I wish I'd known when she made such a big deal about me necking in the car with my high school boyfriend.)

Then dad switched to my childhood, laughing as he recalled me (at 3 years old) telling the towering 6-foot, 4-inch gentleman next door that it wasn't “nice to spit.” He also enjoyed reminiscing about the time he bought my sister boxing gloves so that she could hit me when I picked on her. Our shared laughter felt wonderful.

My father's hearing aids weren't working, which meant that most of our two-hour conversation that day involved him loudly saying, “What?” and me shouting my responses at him. I was exhausted and hoarse by the time he informed me — loud enough for the neighbors to hear — that he had to go to the bathroom.

And it was fine.

Ellie Kahn is a freelance writer, oral historian and owner of Living Legacies Family Histories. She can be reached at ekzmail@adelphia.net.