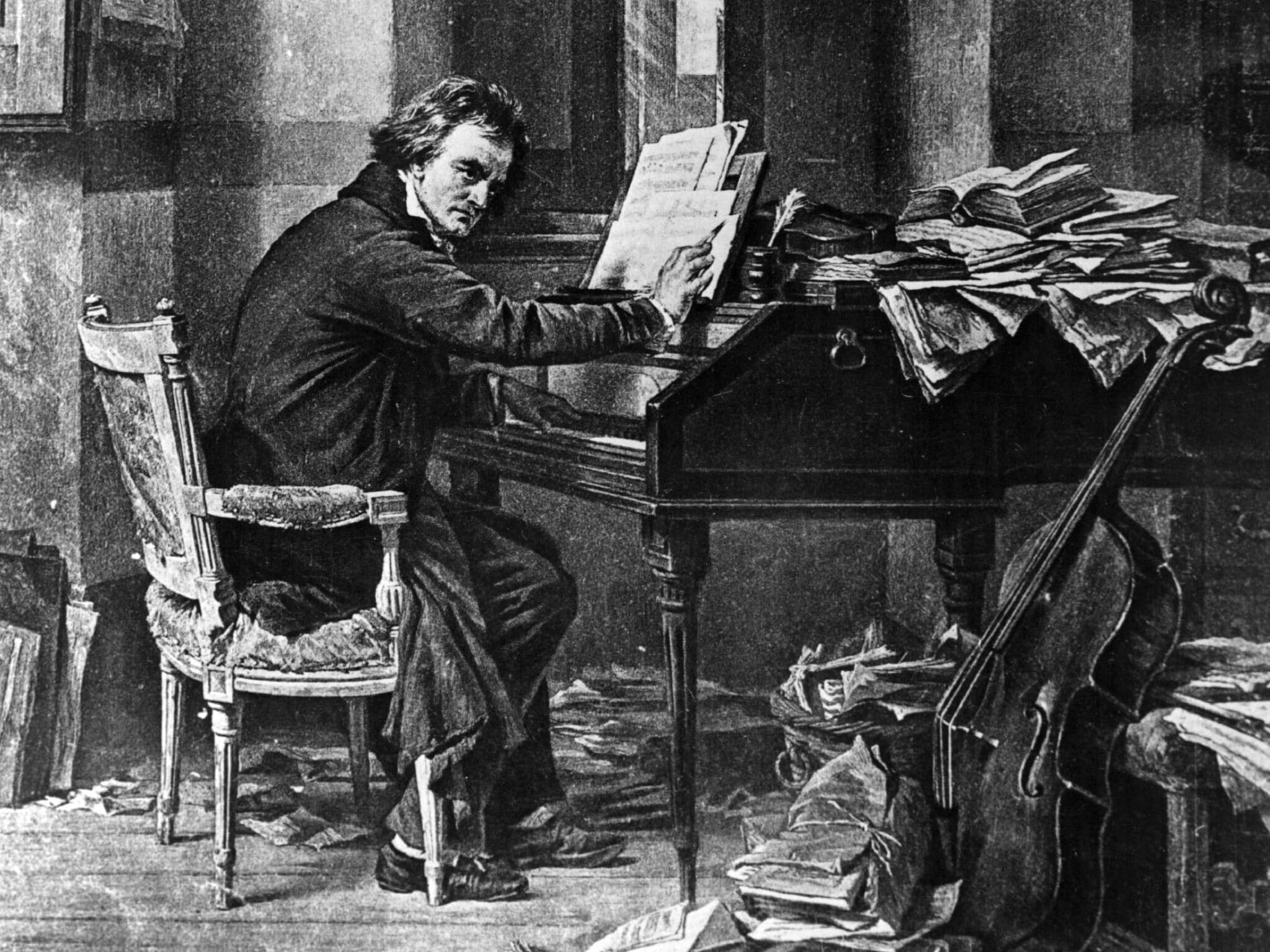

German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) composing at a a piano, circa 1800. (Photo by Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

German composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) composing at a a piano, circa 1800. (Photo by Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) With a well-upholstered air,

I’m comfortable with myself and others,

because I really do not care

for those I used to call my brothers.

I sang them odes of joy, like Schiller

by Beethoven made most melodious,

the truth unfortunately its killer,

making the whole world seem odious,

Like Schiller, I have changed my mind,

most people in the world refusing

to see the Jews as humankind,

while of genocide accusing

my people whom they do not see

as brothers, which the world disgraces,

the concept of fraternity

deprived of any real basis.

We Jews no longer are regarded

by all the world with joy as brothers,

but in dismay dismissed, discarded,

deformed, descended species, others.

In “Liberty in danger: The failure of enlightened hopes” (TLS, 2/2/24), Ritchie Robertson, reviewing The End of Enlightenment: Empire, Commerce, Crisis, by Richard Whatmore, writes:

In May 1789 Friedrich Schiller, already well known for his histories of the Dutch Revolt and the Thirty Years War, delivered his inaugural lecture as professor of history at the University of Jena. His subject was the study of world history. He depicted it as a narrative of progress, increasingly secured by international commerce. Enlightened self-interest ensured that the European powers, too heavily armed to risk war, would maintain peace. “The European society of states seems transformed into a great family.”

By the time Schiller’s lecture was published in November 1789, the Bastille had fallen, the Rights of Man and the Citizen had been declared, the French National Assembly had expropriated the Church and Edmund Burke, appalled, was already contemplating the Reflections, in which he would describe the French Revolution as “the most astonishing that has hitherto happened in the world”. Its subsequent descent into regicide and terror seemed to confirm Burke’s gloomy forebodings and render ridiculous the enthusiasm with which many intellectuals, including Schiller, had initially greeted it. In the essay “On the Sublime”, written at an uncertain date in the mid- or late 1790s, Schiller had changed his mind. He declared that the world, as a historical object, was merely “the mutual conflict of natural forces”, which could never satisfy the ethical demands made by philosophy.

Although Schiller does not appear in The End of Enlightenment, his movement from optimism to disillusionment matches the trajectories of many of the thinkers whom Richard Whatmore discusses. These thinkers are all British, except for the French revolutionary Jacques-Pierre Brissot, who spent several years in Britain and America, and knew such radical thinkers as Catharine Macaulay and Thomas Paine (also prominent in this book). They are united, in Whatmore’s argument, by the reluctant admission that the ideal here attributed to David Hume, “an enlightenment composed of peace, toleration and moderation”, was bound to fail and be replaced by one of numerous possible futures, all of them dark.

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at gershonhepner@gmail.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.