bazilfoto/Getty Images

bazilfoto/Getty Images From crooked timbers Noah built his Ark,

but man’s must be extended, first to soar,

then to descend to plumb what’s deep and dark:

detritus upon the ocean floor.

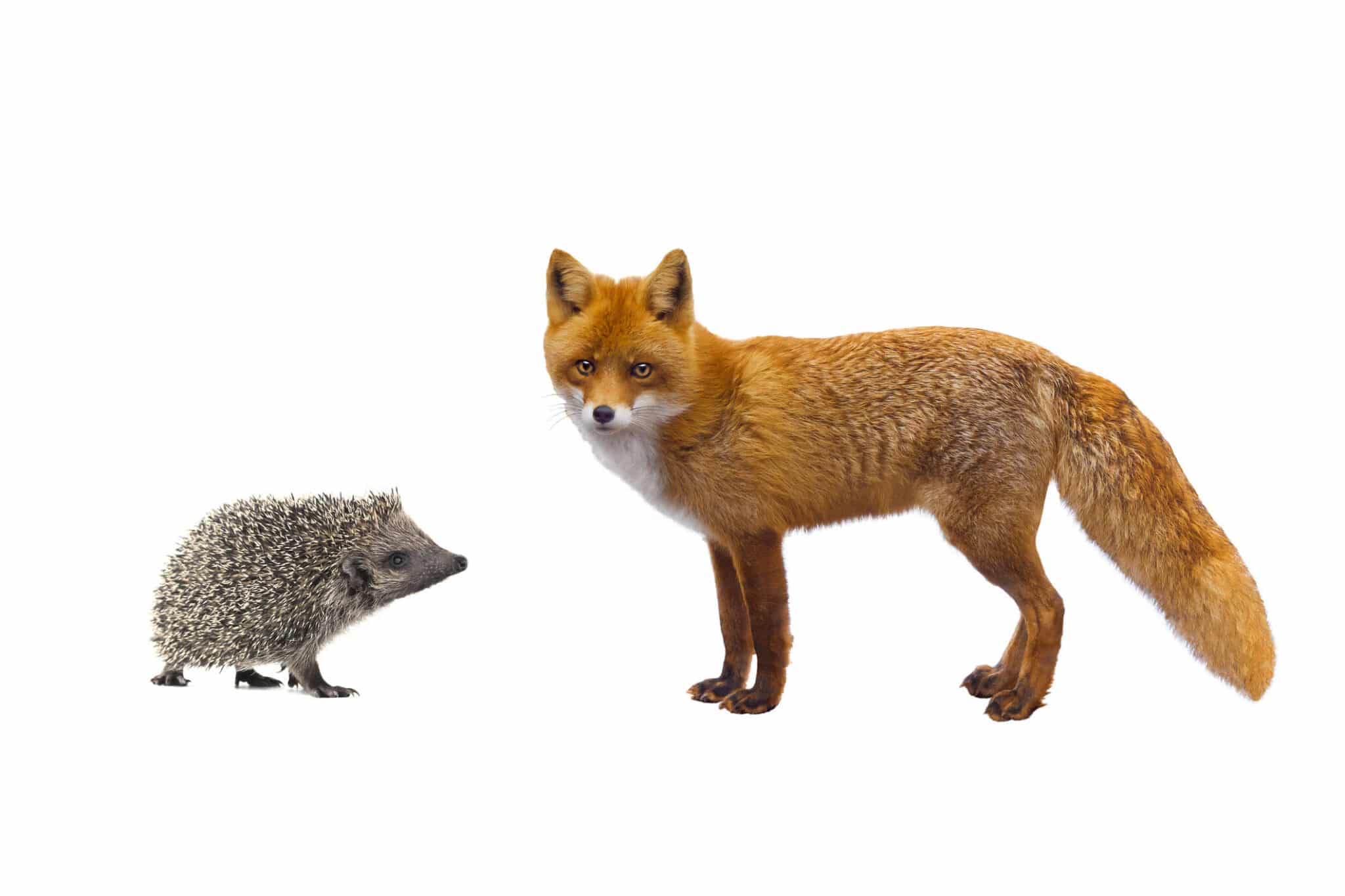

The hedgehog cannot see beyond its nose

and lives contented within crooked timbers;

above tall trees the fox, more curious, knows

vast vistas lie, concealed by darkest nimbus.

If only we could fuse the genes of foxes

with those of hedgehogs, we could reach the stars

helped by the archives stored in mental boxes

to be undeluged by the facts we parse.

With crooked timber our mentality,

unfocussed foxes we, or heedful hedgehogs,

obsesses much about morality,

accepting everybody, cats and dogs,

realizing, naturally, that we

are made of timber that’s not straight enough

for those who are unwilling to agree

with people who are made of crooked stuff.

Ludwig Wittgenstein explained this well.

Like Hegel, hedgehogs see one truth, while foxes,

like Shakespeare seeing many, try to tell

a lot of truths they find in many boxes.

The rabbis state that God created thunder

encouraging our human hearts to straighten

their timber, and correct each blatant blunder

in spite of the Accuser we call Satan.

Kant wrote:

Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.

Marilyn Berger writes an obituary on Sir Isaiah Berlin in the NYT on 11/7/97:

Sir Isaiah’s lectures were often not published and his essays were scattered in so many magazines and journals that his body of work was inaccessible to most people. Henry Hardy, the graduate student, set out to collect it in four volumes that became five: ”Russian Thinkers” (1978); ”Concepts and Categories” (1978); ”Against the Current” (1979); ”Personal Impressions” (1980) and ”The Crooked Timber of Humanity” (1990).

In “Death and the Hedgehog,” NYR, 6/22/23, Gary Saul Morson, reviewing Tolstoy as Philosopher: Essential Short Writings (1835–1910), writes:

Ludwig Wittgenstein, who was deeply influenced by Tolstoy, recognized that faith entails not some doctrine or fact about the world but a different sense of the world as a whole: “It becomes an altogether different world. It must, so to speak, wax and wane as a whole. The world of the happy man is a different one from that of the unhappy man.” This is the conclusion that Levin reaches at the end of Anna Karenina, and if Tolstoy had stopped there, he would have found a faith consonant with the insights of his major literary works.

Alas, Tolstoy went much further, to the point where he rejected War and Peace, Anna Karenina, and most of Europe’s literary and artistic masterpieces. What changed was his very style of thinking. In his famous essay on Tolstoy, “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” Isaiah Berlin—meditating on Archilochus’s gnomic line “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing”—envisaged two types of thinker. Hedgehogs, like Hegel, build systems offering “a single, universal organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance.” By contrast, foxes, like Shakespeare, recognize the variety of experiences that do not form a whole and demand a multitude of perspectives. Berlin recognized both impulses in Tolstoy, who grasped for systems only to shatter them with his relentless skepticism.

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at gershonhepner@gmail.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.