Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images

Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images Let’s assume that when Vice President Kamala Harris decided to speak about Israel and Hamas March 3, it was not an off-the-cuff decision. Let’s assume her speech was thought through, that it had a certain purpose, and that her imminent meeting with Minister Benny Gantz, a member of Israel’s war cabinet, was on her mind. Let’s assume the speech was meant as a message – and let’s try to decipher this message. Does it make sense?

You can read the whole thing. It isn’t long or complicated. And yet, it is difficult to understand. Why? Let’s see what she says, line by line.

“I must address the humanitarian crisis in Gaza.” No, she does not. She wants to address it, but doesn’t have to. A decision to address it is a decision to direct a spotlight at something: Gazans are suffering. It is a decision to emphasize something that complicates the war effort, and could erode Israel’s ability to achieve its objectives. Harris made the choice, maybe because she cares about human suffering, maybe because of political considerations, maybe because she doesn’t believe Israel can achieve its goals. We don’t know why she made this choice, because her speech doesn’t include an explanation.

“Too many innocent Palestinians have been killed.” Had she said “many,” it would have been a state of fact. But she said “too many.” What does “too many” mean? It means that the aim doesn’t justify the cost. Compare this situation to one that Ross Douthat described in a recent New York Times column: “Retaking Mosul from the Islamic State’s fighters … left between 9,000 and 11,000 inhabitants of the city dead.” Now try Harris’ description on that calamity: She could say “many innocent residents of Mosul have been killed.” She could say “too many innocent residents of Mosul have been killed.” The latter means one of two things: Either that U.S. forces could have achieved the same result with fewer civilian casualties – or that retaking Mosul from the Islamic State was not worth the cost in human life. Which of these two critiques does she level at Israel?

“The Israeli government must do more to significantly increase the flow of aid.” This is concrete and understandable. Harris sees people suffer, she demands they get more food and aid. But let’s see what she says next: “They must not impose any unnecessary restrictions on the delivery of aid.” They – namely Israel – must not impose unnecessary restrictions. Well, that’s obvious, isn’t it? Why would anyone do something that’s unnecessary? Clearly, what she means to say, and that’s quite clear, is that Israel does impose unnecessary restrictions. Let’s see what else Harris says.

“Hamas cannot control Gaza, and the threat Hamas poses to the people of Israel must be eliminated.” This is a strong statement. It means that the U.S., at its core, still supports Israel’s stated aim of the war: eliminate Hamas rule. But how does one eliminate Hamas rule? By waging war. And what happens in such a war? People suffer. One can’t conquer Mosul – or Gaza – without extracting cost. But since Harris is still on board concerning the goal of the war, the criticism she levels at Israel is apparently of the first type we mentioned: “the same result could be achieved with less civilian casualties”.

But here’s a question Harris does not answer: What would be the trade-off? I see three options. One – she believes that there can be less human suffering at no cost. If that’s her assumption, it’s easy to understand her sentiment, but let’s say that such an assumption is not realistic. There must be a trade-off involved in any change of war tactic. Two – she believes that Israel can take more risks to its own soldiers, as it attempts to ease the suffering of Gazans. If that’s the case, Israelis beg to disagree (and Americans would also disagree had she proposed a similar remedy in the case of American soldiers in Mosul). Three – she is willing to risk Israel’s ability to come out victorious from the war. In such a case, her “Hamas cannot control Gaza” part of the speech is less than genuine.

“Hamas claims it wants a ceasefire. Well, there is a deal on the table. And as we have said, Hamas needs to agree to that deal.” This is where I got confused. Is Harris sending a message to Israel or Hamas? Let’s say Hamas does not accept Harris’ demand — does this cancel her previous demands of Israel? Or maybe she sees these two demands (Hamas accepts a deal, Israel does not impose unnecessary restrictions) as separate and independent of one another?

Let’s take her speech as a general guideline on what to do next. Is it a useful guideline, or just a wish list of things that can only be imagined as compatible in a speech rather than in reality?

Confusing or not, let’s assume she means well. Let’s take her speech as a general guideline on what to do next. Is it a useful guideline, or just a wish list of things that can only be imagined as compatible in a speech rather than in reality?

As they say, only time will tell.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

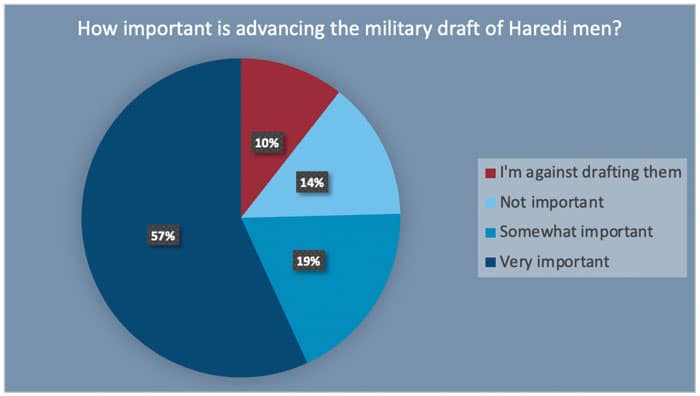

The end of March is the deadline on Haredi draft negotiations, so this topic stays with us, and is a threat to the stability of the government. Here’s what I wrote this week: What will be the working tools of the ultra-Orthodox politicians in the draft negotiation? There will be three. First – a threat to overthrow the government. If the government falls, it will be impossible to move the draft forward for some time. The second tool is seduction. Give us what we want – they will say to Benny Gantz – and we will make you prime minister. The third tool is the control of details. The ultra-Orthodox will accept certain principles, but will make sure that the actual arrangement does not bring about a significant change in reality itself.

A week’s numbers

Opposition to the draft is law, but there’s strong resistance within the coalition parties.

A reader’s response:

Asher Katz wrote: “Do Israelis still think Biden is a friend?” My response: I’ll tell you next week, when I get the results of a new poll we commissioned.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.