shmooj/Getty Images

shmooj/Getty Images Ask Israelis, and most of them will tell you that they want another war: A war on the northern border. And it is not because they are trigger happy or bloodthirsty; it is because they see no other way out of a northern trap – and feel that it’s better to fight now than wait for another day.

Ask Israel’s government what it intends to do, how it intends to rescue Israel from the northern trap and you get nothing other than platitudes. The government’s official position is to work for some kind of a diplomatic solution that would save Israel the need for war. What can it be? For Hezbollah to accept the demand of the U.S. or France or the UN and willingly move its forces northward, away from the Israeli border. The prospect for such a diplomatic plea to succeed is – let’s be polite – slim. Resolution 1701 was unanimously approved by the United Nations Security Council on August 2006, and the result … well, you probably know there was no “disarmament of all armed groups in Lebanon,” as the resolution demands, nor was the call for “no armed forces other than UNIFIL and Lebanese… south of the Litani River” answered.

Israel tolerated this situation for almost two decades since the end of the Second Lebanon War (2006), but can no longer tolerate it. Why? Because of Oct. 7. When Hamas infiltrated Israel and mercilessly butchered, raped, maimed and defiled Israelis, it shocked us all into understanding what could happen on all borders if we – Israelis – don’t stay alert. Most of all, it could happen on the northern border, where Hezbollah’s elite Radwan Force is stationed for exactly this purpose: wait for the call to cross the border, kill, occupy and terrorize Israel.

Until Oct. 7, Radwan’s presence was a looming threat. After Oct. 7, it is a clear and present danger.

Now comes the hard part: Deciding what to do. Israel evacuated all civilians from the northern border – they are, and the terminology is important in this case, refugees within their own country. They cannot go back to their homes as their homes are bombarded by Hezbollah and are located in dangerous proximity to Radwan forces across the border. So, Israel must provide them with one of three solutions: One – provide them with alternative places to live (and by doing this, turning Israel’s northern region into a no man’s land). Two – find a way to move Hezbollah northward without war (you already know what I think about the likelihood of such a plan). Three – go to a bloody and dangerous war against Hezbollah. Option Four – for Israel to somehow convince itself and its citizens that things can go back to normal by merely getting a cease fire – that’s the option Israelis feel is the true trap.

If most northerners refuse to go back to their homes and gather in Jerusalem to protest until the matter is satisfactorily resolved, then the government will face a huge challenge. Clearly, it cannot afford to lose the north because of Hezbollah intimidation.

Does this mean Israel is likely to start a war against Hezbollah? That depends on many questions that we can’t yet answer: How long is the war in Gaza going to last; how decisive would be Israel’s victory in the south; how far would Hezbollah go in provoking Israel into action; how severe would be the diplomatic pressure on Israel not to start a war (for various reasons, the international community is much better at pressuring Israel than at pressuring Hezbollah); what would be the political situation in Israel. Last but not least: what would northern Israelis do? In fact, that would probably be the most decisive factor as we look into the future of the northern border. If most northerners reluctantly submit to an uncomfortable situation, sugarcoated by some kind of hastily arranged agreement, a war could be avoided. But if most northerners refuse to go back to their homes and gather in Jerusalem to protest until the matter is satisfactorily resolved, then the government will face a huge challenge. Clearly, it cannot afford to lose the north because of Hezbollah intimidation. Clearly, a war is going to be costly and could put Israel under immense diplomatic and economic pressure.

Earlier this week, it was reported that the USS Gerald R. Ford aircraft carrier strike group will leave the eastern Mediterranean Sea. It was sent there shortly after the start of the Gaza War and was considered a tool with which the U.S. attempted to deter Hezbollah from starting a second front against Israel. Why is it leaving? Details weren’t clear. The position of the U.S. concerning the Hezbollah threat is also unclear: It seems to want to prevent a war by putting pressure mostly on Israel. It seems to want to prevent a war by getting involved in the negotiations that could lead to the agreement whose aim is to convince northern Israelis that it is now safe to go back home.

It will not be safe.

It will be a trap.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

There are two problems with the traditional division of Israel into two political blocks. One – such a division generates polarization. Two – it does not necessarily reflect Israeli reality.

Why it generates polarization is quite clear … Why does it not reflect reality? Because it assumes that there is a distinct common denominator that unites each of the two blocks (or at least one of them), but this is not the case. The blocs were created as a political arrangement under certain circumstances, a package deal to consolidate power. But the commonality between a United Torah Judaism voter and a Likud voter is not necessarily greater than the commonality between a Likud voter and an Israel Beitenu voter. The commonality between a religious Zionist voter and a Shas voter is not necessarily greater than the one ground between a Religious Zionist voter and a Yesh Atid voter.

A week’s numbers

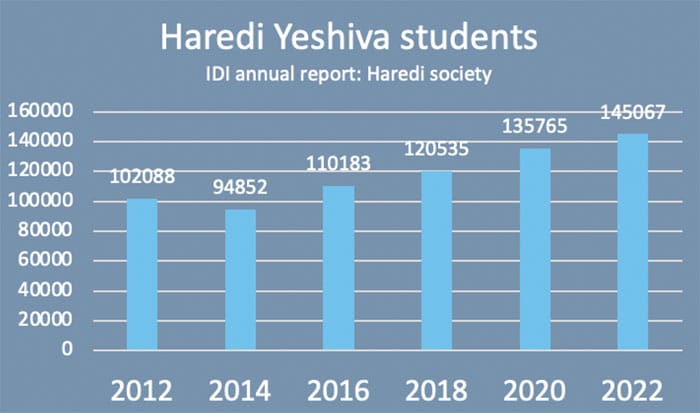

There was just one period of slight decline in the number of Haredi Yeshiva students who get a stipend to study rather than serve in the IDF and work: The time in which the Haredi parties were not part of the ruling coalition.

A reader’s response:

Ari Gould asks: “I get the impression that Israeli society is becoming polarized again, is that true?” My answer: Yes – not as polarized as before, but it’s clear that old wounds are still there.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.