Reuters/David W Cerny

Reuters/David W Cerny On March 9, 1790 — 14 years after signing the Declaration of Independence — a dying Benjamin Franklin responded to a letter from Yale President Ezra Stiles, who wanted to glean some final wisdom from one of the great founders of the United States.

“Here is my Creed,” Franklin wrote. “I believe in one God, Creator of the Universe. That He governs it by his providence. … That the most acceptable service we can render to him, is doing good to his other children. That the soul of man is immortal, and will be treated with justice in another life respecting its conduct in this. These I take to be the fundamental principles of all sound religion, and I regard them as you do, in whatever sect I meet with them.”

It is fascinating to me that Franklin, who never stylized himself as dutifully religious, would look to faith upon the mortal turn. There is something sacred about life that draws us closer to transcendence when we reach its margin. We ask ourselves, when we winnow away the day-to-day struggles: What catches flight in the wind never to be thought of again, and what remains for the next generation? What are our most fundamental creeds? What is our personal wisdom we wish to share?

These same questions permeate Devarim, the final book of the Torah. This book is unique in the Torah for its literary style and composition. It has no narrative to speak of and the stories it does tell are in the form of remembrance of times past, a retelling of the history of the people wandering the desert, testing one another and testing God.

The only true narrative is in the final chapter, where Moses climbs the mountain and dies. His impending death dominates the book, as many scholars have pointed out. Taken at face value, the Book of Deuteronomy takes place on a single day, “On the first day of the eleventh month in the fortieth year” (Deuteronomy 1:3), the day of Moses’ death.

Even more than the founders of our country, Moses, the religious personality incarnate, feels the transcendent need to impart his deepest beliefs to the next generation. Moses lifts his weary bones and ascends to speak to the very people he liberated and bore across the desert in partnership with God.

It is here, in Devarim, that Moses spends his last breaths exhorting the people to remember who they are and where they come from. It is in Devarim that we find our only credal statement, the Shema: “Listen, O’Israel, The LORD is our God, the LORD is One.” (Deuteronomy 6:4).

It is in Devarim where Moses lays out his dreams for his people as a nation settled in the land, prosperous because they know they are bound up in history and covenant. It is in Devarim where Moses demonstrates to the people that there is a choice between being blessed and cursed, between life and death, and that we the people are to choose life (Deuteronomy 30:19).

The Book of Devarim is Moses’ legacy letter to the Jewish people that captures his collected wisdom over a lifetime. While none of us will found a nation or be a prophet of God, we do, however, have our own lives to share with others. Every one of us lives out a personal epic story that spans our entire lifetime. As Jews, we come from an ancient and storied people. God willing, each one of us also can become an ancestor, sharing our collected wisdom with our children and grandchildren. What will be your legacy letter? What if you wrote that letter to your descendants now? And perhaps, most important, what if you wrote it to yourself now?

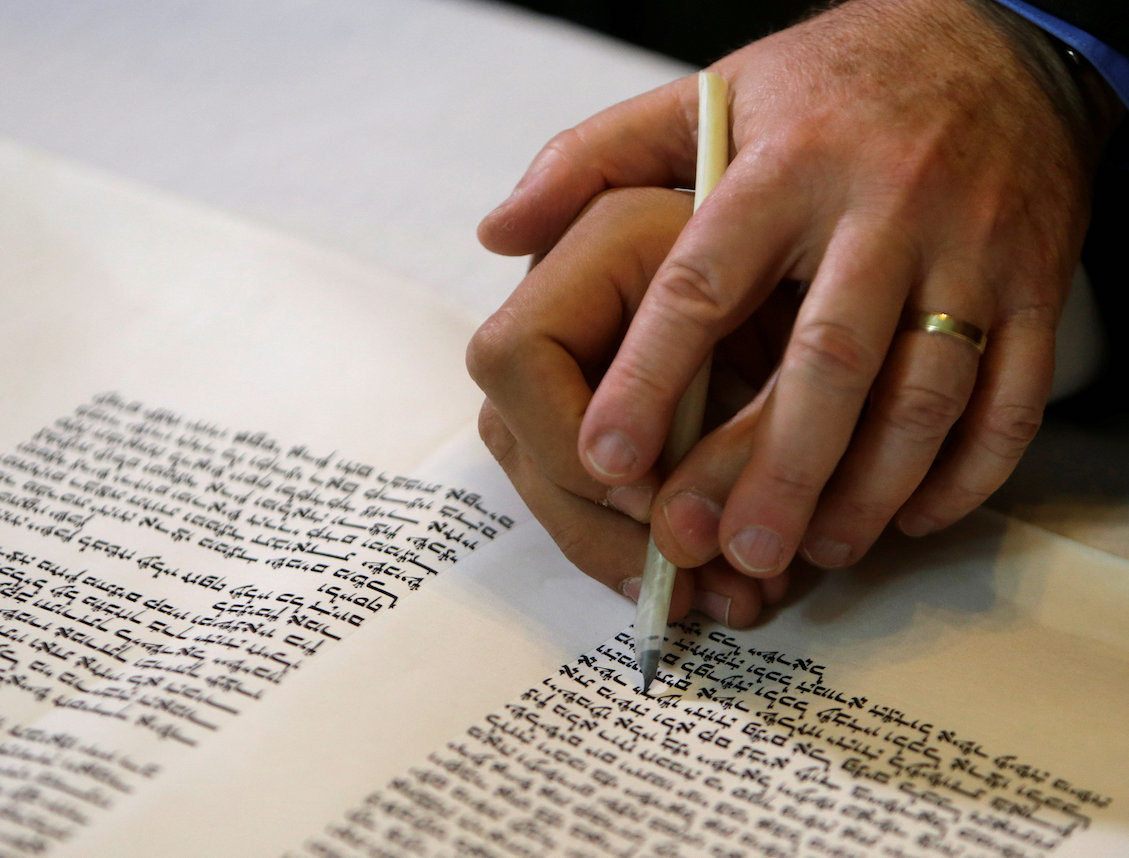

The 613th mitzvah, the very last commandment in the Torah, is to write your own sefer Torah, a sacred scroll, a guidebook for life. Moses fulfills this final mitzvah on the day of his death, sharing his legacy with the next generation. Many of us can’t write the actual words of the Torah, but try to take some time to write your personal version. Like it did for Franklin and Moses, this task can bring clarity of purpose and devotion for these wonderfully short days we spend together in life. You will be glad you did.

Rabbi Noah Farkas is a clergy member at Valley Beth Shalom in Encino, founder of Netiya and the author of “The Social Action Manual: Six Steps to Repairing the World” (Behrman House).

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.