“An eye for an eye.” Critics cite this Biblical punishment to indict Judaism for being an unforgiving, legalistic religion. This verse has become theological shorthand for a rules-obsessed religious outlook that is heartless and harsh. In many instances, this critique morphs into anti-Semitism; when Shakespeare’s Shylock craves a pound of flesh, he echoes centuries of anti-Jewish polemics about “an eye for an eye.” And to this day, critics of Israel invoke “an eye for an eye” to describe Israeli actions, a trope inextricably intertwined with antisemitic slanders of the past.

The roots of this allegation are found in the New Testament, in the Sermon on the Mount. In it, Jesus teaches his disciples that they should reject “an eye for an eye”: You have heard the law that says the punishment must match the injury: ‘An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say, do not resist an evil person! If someone slaps you on the right cheek, offer the other cheek also. …. Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you… In this passage, the New Testament roundly rejects an eye for an eye; but at the same time, it shackles Judaism to this barbaric practice.

But that is not what Judaism teaches. Jewish interpreters are adamant in declaring that “an eye for an eye” is not meant to be understood literally. The Talmud offers a half a dozen arguments to prove that the text must mean monetary compensation; Benno Jacob argues, that by definition, the Hebrew word “tachat” in this verse can only mean an actual repayment. On a practical level, it would seem impossible to implement the punishment of “an eye for an eye” in a fair manner; removing an eye, (certainly, in ancient times,) would result in a disproportionate injury, and could even end up killing the accused.

One could stop the discussion here by saying that in practical terms, “an eye for an eye” is essentially fiction. But there are lessons to be learned from the literal interpretation of the text as well. How one understands “an eye for an eye” relates to a much larger question: what is justice?

For many Christian readers, the Sermon on the Mount teaches that one must pursue the exact opposite path from “an eye for an eye.” Pope Francis, in a 2013 sermon, explains that this a rejection of human conceptions of justice:

If we live according to the law of “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”, we will never escape from the spiral of evil. The evil one is clever, and deludes us into thinking that with our human justice we can save ourselves and save the world! In reality, only the justice of God can save us!

To do good to them that hate you is the very path to redemption; and that requires an emphasis on transforming criminals.

Without question, any discussion of crime and punishment must consider the importance of rehabilitation. As the Talmud (Berakhot 10a) puts it, Judaism also hopes to uproot sins and improve sinners. To this end, reformers endeavored to turn prisons into penitentiaries, places where criminals would repent from their crimes. Educational and work opportunities were provided to prisoners to help them rebuild their lives, and over the years, some excellent programs have found significant success. Love does make a difference, and encourages people to change. But when taken to an extreme, the path of love fails; replacing the local police force with a cadre of social workers will only lead to more crime. Love can never replace justice.

For this reason, “an eye for an eye” deserves a second look.

There are many rabbinic thinkers, including Maimonides in the Guide for the Perplexed, that find lessons in the literal meaning of “an eye for an eye.” Rabbi Moise Tedeschi, in his Hoil Moshe, explains that “an eye for an eye” was meant to be understood literally during Israel’s early history. The former slaves struggled to build a civil society, and it was a time of chaos; harsh punishment was necessary to instill a sense of law and order. It is only later, at a time of greater stability, that “an eye for an eye” could be interpreted as a monetary payment. In other words, “an eye for an eye” was a type of martial law, and only intended for a short period of history.

This interpretation highlights the importance of deterrence. Crimes must be punished as a warning to others; without severe punishments, society will dissolve into anarchy. At times, extreme measures are necessary for the greater good, even if they are as brutal as “an eye for an eye.”

But the most significant lesson of “an eye for an eye” is that punishment is part of the pursuit of justice; and in the case of a bloody assault, retribution is required. Rabbi Ovadiah Seforno writes that “an eye for an eye” is what ought to be the judgment against the offender, if we were to apply the principle of the punishment fitting the crime in all its severity. There is a profound injustice in allowing someone who assaulted his neighbor to pay his way out of the crime. Emanuel Levinas points out, this justice based on peace and kindness… leaves the way open for the rich! They can easily pay for the broken teeth, the gouged-out eyes, and the fractured limbs left around them. The world remains a comfortable place for the strong,… Yes, eye for eye. Neither all eternity, nor all the money in the world, can heal the outrage done to man. It is a disfigurement or wound that bleeds for all time…

“An eye for an eye” is, in the end, a theoretical proposal. Ultimately, all physical punishments were abandoned and considered cruel; they were replaced with incarceration, which matches the severity of corporal punishment without inflicting any physical pain. But the lesson of “an eye for an eye” remains; justice demands that evildoers be punished, and a society that indulges criminals is itself criminal. When writing about how it is critical for a sovereign to pursue “the equalization of punishment with the crime”, Immanuel Kant explains:

(Punishment) ought to be done in order that every one may realize the desert of his deeds, and that bloodguiltiness may not remain upon the people; for otherwise they might all be regarded as participators in the murder….

It is easy to diminish justice; it is the gruff, offputting, hard-edged counterpart of love. But love doesn’t conquer all; you need to have order and civility first in order for love to flourish. And that is impossible without justice.

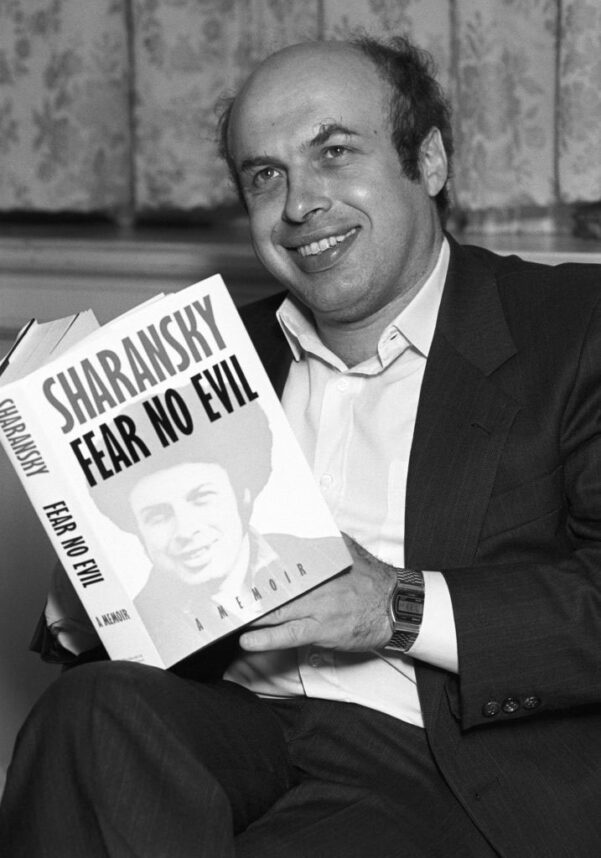

Lenn Evan Goodman begins his book On Justice with the following anecdote. As a child in Los Angeles, he had a Hebrew school teacher, Dr. Lubliner, who, when he rolled up his sleeves on hot days, exposed a pale blue tattooed number on his forearm. Dr. Lubliner was a man of great dignity and learning. He had much to teach, but almost never spoke about the Holocaust. But one time, in a tangentially connected discussion, Dr. Lubliner interjected: “I believe there’s justice in the world…there must be justice.”

Goodman adds that another time he arrived at Hebrew school early, and saw Dr. Lubliner silently saying the Mincha prayer. At that moment Goodman thought to himself: “if a man like that can believe in God, so can I.”

Love may be transcendent, but that is not enough on its own. To believe in God is to believe in the possibility of ending the rule of evil, and that all wickedness will vanish like smoke.

There must be justice in the world too.

Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz is the Senior Rabbi of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun in New York.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.