A couple of weeks ago, my husband sent me a link to a local Krav Maga club. He was thinking of signing up for a free trial and also taking our 16-year-old son.

I would like to say my husband’s motivation was to improve his fitness; he is an avid runner, but he doesn’t do any weight-training. Or maybe I wish it were a desire to relieve stress — isn’t that one of the benefits of martial arts? But I knew as soon as he mentioned Krav Maga that he was thinking about pure and simple self-defense. He works in a university, where people regularly march through campus shouting “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free!,” which might have a contested meaning but feels threatening nonetheless. We live adjacent to a neighborhood that is majority Muslim; almost every window has either the river-to-the-sea motto or some other all-caps angry sign directed at Israel, where many members of our family live. We avoid the weekly ceasefire protests in our city because they often include blatantly antisemitic slogans and illustrations, such as “Khaybar Khaybar ya yahud jaish al Mohammed sauf yaud” — a reference to a historical massacre, which translates to “Khaybar, Khaybar, oh Jews, the army of Mohammad will return” — and “Keep the world clean,” with a Magen David shown tossed in the trash. I guess a lot of us are thinking about self-defense these days.

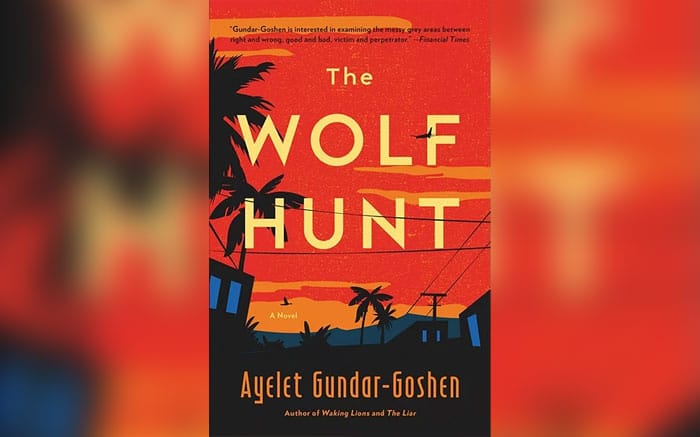

When Ayelet Gundar-Goshen’s recently published fourth novel, “The Wolf Hunt,” came out in English this past summer, I read it thinking about Lionel Shriver’s “We Need to Talk about Kevin.” Both are novels about high school murders, and both investigate the relationship between a mother and son. In both cases, the mother, who is the protagonist, is revealed to be an unreliable narrator, leaving readers unsure about her son’s capacity to harm others. Both are deeply psychological novels, asking how much we can know anyone. I loved “The Wolf Hunt” as I loved “We Need to Talk about Kevin.”

In the wake of October 7, I reread Gundar-Goshen’s new novel, this time thinking about the responses to the attack on Israeli soil. It felt like a completely different book.

In the wake of Oct. 7, I reread Gundar-Goshen’s novel, this time thinking about the responses to the attack on Israeli soil. It felt like a completely different book.

Already, in my first read, I could see where Shriver’s and Gundar-Goshen’s novels diverged, chiefly in what we can conclude about the sons, but also because of the role that national identity, culture and attitudes play. Although both are set in the U.S. and have a clear American context, in “The Wolf Hunt,” Lilach is an Israeli transplant to Silicon Valley. Lilach’s Israeliness — or rather, her in-betweenness as an Israeli-American — is significant. Her failure to understand her son, Adam, comes, at least in part, because he is American raised. She also struggles to really know her husband, Mikhael, because of the position he held in the Israeli Defense Forces, a position that was formative to his character; his “military ID had been branded into his flesh with a white-hot iron along with an order for eternal secrecy,” she says.

But now I also see how the distinction between aggression and self-defense makes these books rather different beasts. Shriver’s book tracks the growth and development of a boy who seeks to do harm. Gundar-Goshen’s is about averting harm — though this trajectory, too, can have dire consequences.

“The Wolf Hunt” begins with a sadly all-too believable, too familiar premise, set not long after the Pittsburgh Tree of Life and Chabad of Poway attack: A man walks into a synagogue on Rosh Hashanah in the Bay Area and stabs a young woman to death.

After the synagogue stabbing, there is a panic among the Jewish residents, and a desire to fight back against antisemitism. For Gundar-Goshen’s born-and-raised diasporic Jews in California, there are committees and meetings. For her Israelis, however, the fight involves hard-core self-defense: Krav Maga.

Lilach, our heroine, is plainly conflicted. On the one hand, she doesn’t like the macho Israeli attitude that she sees as potentially damaging. On the other hand, she observes with dismay the way her nephews, visiting from Israel, get up early, run, make protein shakes, are “strong and tan, loud and brash”; in comparison, her son Adam plays video games, is not athletic, and “trailed after [his Israeli cousins] like a dog hoping to be adopted.” Embedded in Lilach’s consciousness is the fear that, as the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor who had been in the camps, she has passed down to her son “the gene that has like sheep to the slaughter written on it.”

So, Lilach encourages her son to join the new Krav Maga classes.

We know from the outset what will happen because Lilach tells us on the very first page. There is an African-American boy at Adam’s school, Jamal, a follower of the Nation of Islam, a bully, and when he dies suddenly, her son stands accused of his death: “They say he killed Jamal.”

Is Adam guilty? Although “The Wolf Hunt” functions as a kind of mystery novel (and in that sense, is a real page-turner), it is Gundar-Goshen’s explorations of terror, fear, revenge, solidarity, parental protectiveness, self-defense and the Israeli psyche that makes this novel worth reading — particularly now. But my main beef about this book is that it ended. It kept me spellbound, and I hope this isn’t Gundar-Goshen’s last.

Karen Skinazi, Ph.D is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of “Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.