Not every Jewish immigrant from Russia and Eastern Europe who landed at Ellis Island ended up in Brooklyn or the Lower East Side. Some of them reached such unlikely destinations as the chicken farms of Petaluma and the frozen wastes of North Dakota. Relatively few of them, however, tried to make a new life in the heart of the Deep South. “A Story of Jewish Experience in Mississippi” by Leon Waldoff (Academic Studies Press) is a heartfelt but also meticulously researched and deeply insightful account of one family that did.

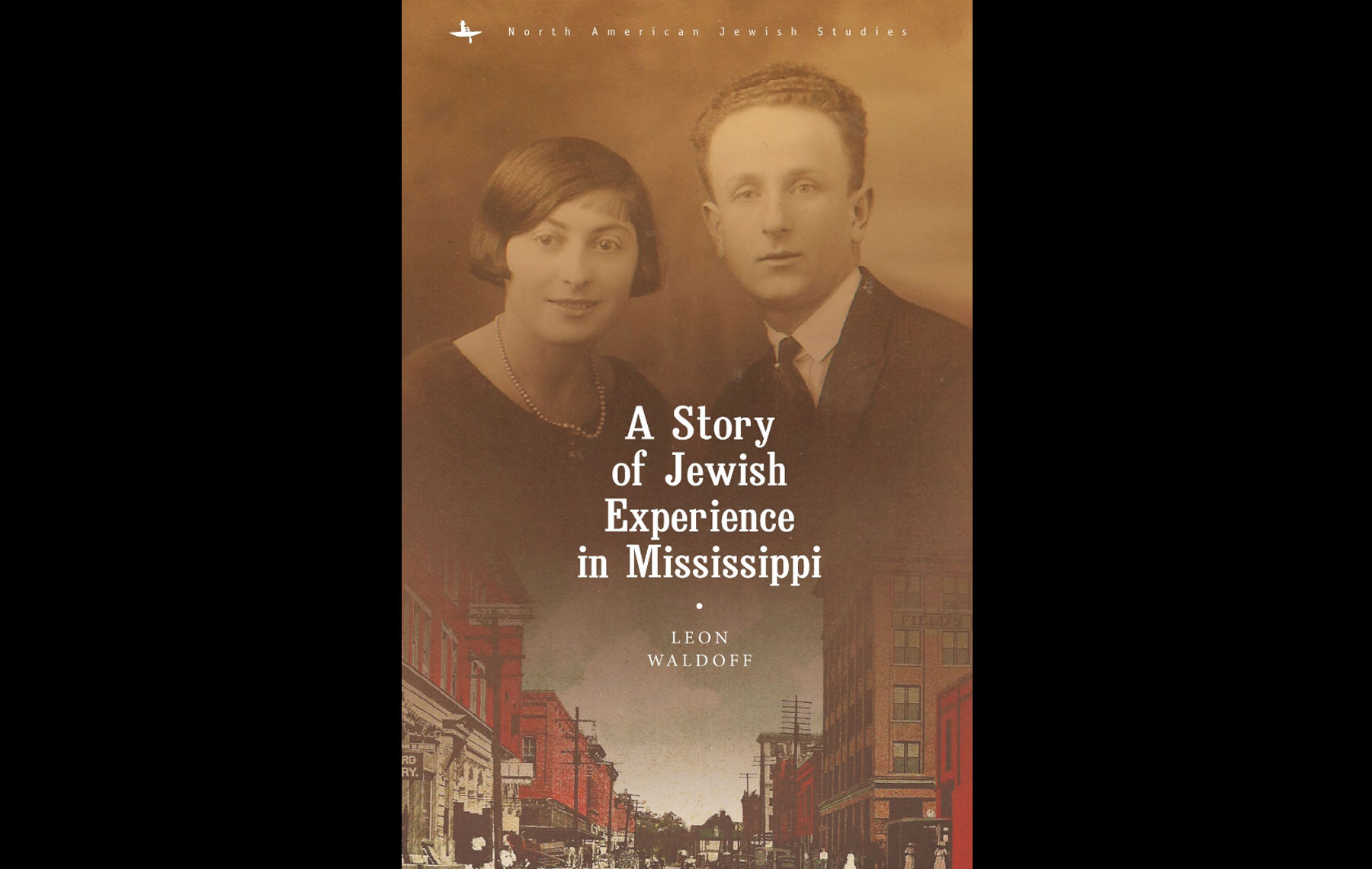

Waldoff, professor emeritus of English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, spent his academic career in the study of Keats and Wordsworth, but he has not forgotten his own roots in the backwater town of Hattiesburg, Miss. His new book is a fascinating but unfamiliar variant of the Jewish American saga, one that is rooted in the letters his parents exchanged, first when they courted in the old country and then after they arrived in America, and the stories that were later told around the family table in Mississippi.

His parents managed to reach the United States in 1922, shortly before the tightening of U.S. immigration law “virtually closed the door” to Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, as Waldoff explains, “making it extremely difficult during the 1930s for Jews fleeing Nazi Germany to come here.” His mother’s family had already settled in Hattiesburg, and his father joined them with some trepidation: “Mississippi, from what they may have heard of it, and so far away, may have seemed an American Siberia,” Waldoff writes.

The Jewish community consisted of some 150 souls, and many of them earned a living as peddlers and merchants. “My father carried his merchandise in a pack on his back and suitcase in his hand,” Waldoff writes. “What was in it? Probably a very limited selection of dresses, blouses, gowns, underwear, pants, shirts, ties, shoes, sox, belts, suspenders, piece goods, patterns, thread and needles.” Whether the customer was white or black, however, the encounter carried the constant risk of misunderstanding and conflict.

“He had to be sensitive to the prejudices of whites and the feelings of blacks while trying to communicate in a language still strange to him as he had first heard it in the Bronx, often mixed with Yiddish words and inflections, now sounding so different in the slower speech, pronunciation, and idioms of the rural South, and even more strange in the different southern dialects spoken by whites and blacks,” Waldoff explains.

By 1929, “Waldoff’s” was proudly displayed on a clothing store on Mobile Street in Hattiesburg, but the racial divide in the South continued to present challenges to the family business. By rigid tradition, for example, black customers were not allowed to use the changing rooms, although they could sit next to a white customer while trying on shoes. Not until he undertook the research for his book did Waldoff fully understand the unspoken rules that governed race relations in the Deep South.

“Precisely because they, too, were the targets of bigotry, some Jewish citizens in the South felt obliged to join in the racist assumptions and practices of their white neighbors and customers.”

“It’s here, in the silent, habitual adherence to the customs of segregation by both blacks and whites that I see at least a partial explanation of why I failed to see that blacks were not allowed to try on clothes before buying,” he writes. “I think I was so blinded by the segregationist culture in which we lived, despite my increasing awareness of its injustices as I grew older … that I still remained unaware of many of the daily humiliations that blacks were subjected to.”

Ironically, Waldoff points out the cruel interplay between racism and anti-Semitism. Precisely because they, too, were the targets of bigotry, some Jewish citizens in the South felt obliged to join in the racist assumptions and practices of their white neighbors and customers. “Given the many false notions about Jews and explicit expressions of anti-Semitism in the 1920s and 1930s, Jews in the South lived with ‘a pervasive sense of anxiety,’ ” he points out. “Although a tiny minority, their clothing and other retail businesses gave them a highly visible presence. They were viewed as ‘the eternal alien.’ ”

By the 1950s, the Jewish community in Hattiesburg felt the freshening winds of the civil rights movement that was manifesting itself across America. Waldoff credits the arrival of Rabbi Charles Mantinband in 1951 for alerting his community and his congregation to the challenge. Some congregants “wanted him to remain silent on the subject of civil rights,” Waldoff concedes, but it was also true that “many of his fellow rabbis in the South had the highest regard for him precisely because he did speak out despite a number of threats.” For Rabbi Mantinband, Waldoff writes, “segregation was ‘the supreme sin of our day’ and ‘as monstrous an evil as any in our Western civilization.’ ”

The author is willing to ask hard questions of himself and his relations when contemplating how and why the Jews of Hattiesburg participated in the strange new world in which they found themselves upon arrival in the land of the free. He recalls, for example, the experience of attending minstrel shows where he “laughed at the puns and jokes and enjoyed the songs, still blind to the racist nature of the merriment.” Now he is able to take a more critical stance: “What would Jews in Germany or Poland have thought, I wonder, about a satirical equivalent of the minstrel shows I saw based on stereotypes of Jews?”

That empathetic question, of course, is biblical in its origins. We are taught in our tradition that we know the heart of the stranger because we, too, were slaves in Egypt. To his great credit, Waldoff suggests throughout his affecting book that the Jews in Mississippi and elsewhere in the Deep South could have and should have recognized their common cause with their black neighbors far sooner than they did. And yet, to the credit of the Jewish leaders and activists that he also writes about, Waldoff demonstrates that the Jewish community, once roused to action, joined the struggle with strength and good courage.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.