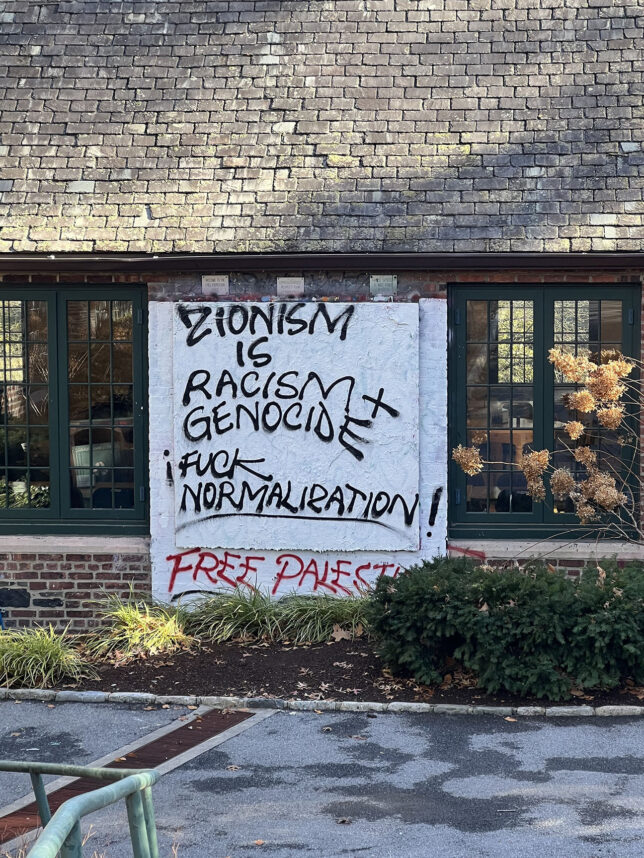

Daniel Joseph Martinez has a question, or, rather, he wants you to have one. Well-known as one of the art world’s favorite provocateurs, the Los Angeles native and resident has brought his unique brand of art-as-conversation-piece to Culver City’s Roberts & Tilton Gallery for his first L.A. gallery exhibition in a decade, “I Am a Verb.” But why is Martinez, a non-Jewish artist, getting coverage in the Jewish Journal? Well that’s simple, really; one of the works he made for the show is a series of photos of a hunchbacked, masked man with the Shema tattooed on his chest, along with a Muslim prayer inscribed in Arabic on one arm and a Catholic prayer in Latin on the other.

“This show is … a constellation of gestures … that are both philosophical and poetic, but yet use very disparate languages to attempt to question the state of who we are as human beings, and to question the time that we live in,” said Martinez on a recent Friday morning, strolling through the installation of his work. “It’s sort of like a series of haiku.”

Martinez has been active in the art world for more than 30 years, but he first rose to prominence in the early 1990s after making a lapel pin, of the sort often used for museum visitors, which was distributed to all attendees of the 1993 Whitney Biennial in New York. A simple inscription on the pin read, “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be White,” and it was worn by visitors of all races and ethnicities — including white — while viewing the rest of the art in the exhibition. Martinez thereby made everyone participants in his questioning reality, and he used language that was specifically intended to provoke the status quo in a zeitgeist consumed by political correctness.

Since then, Martinez has continued to challenge his viewers, and he’s spoken often about how his upbringing in the tumultuous Los Angeles of the 1960s influenced his views on multiculturalism and the notion of who is the outsider. Born in 1957, Martinez has by now become a fixture in the international art scene, his work included in museum collections worldwide.

Upon entering Roberts & Tilton, you’re confronted first by a large, white room, where the sound of Muslim prayers echoes throughout. From one wall, an abstract, sculptural mirror juts out; on another, a crookedly hanging police shield displays a strange manifesto scrawled across it that references both butter and betrayal; and, finally, across the room, the display of four massive photographs of the strange, hunchbacked, masked male figure.

At first glance, this collection of objects couldn’t be more disparate — in their media, subject matter and style — but Martinez is quick to explain the reasoning behind their juxtaposition. “There’s some attempt here to put a series of different kinds of works that take iconic or institutional positions from the society and compress those together.”

It’s easy to see how the police shield, the Arabic music and the religion-tattooed hunchback follow this line of thought, but the abstract mirror takes a little more explanation. A quick trip to the adjacent room reveals that what once looked like a pedestal with a mirror on it randomly jutting from a wall is actually a replica of the base of the Statue of Liberty, looking as if it had been forced through the wall and become stuck there.

“The same sculpture, which is the Statue of Liberty on one side, looks like completely abstract minimalist gesture,” Martinez said, explaining his trick. “The Statue of Liberty pierces the wall; it’s been toppled. You think of the monuments of Lenin, you think of the monuments of any empire that is in ruins or in decline, or [where] something has changed, those monuments get toppled.”

Liberty’s extinguished torch reaches out toward the neon lights of two signs on a wall opposite that blare “We Buy Gold” and “Facial Waxing,” the light and language of the streets. “I’m not sure what the Statue of Liberty represents today other than a tourist attraction,” Martinez said. “A lot of what we do, and a lot of what has meaning, gets turned into entertainment.”

Walking back around to the other side of the wall, Martinez pointed to the mirrored base of the statue. “When you look at the bottom of the Statue of Liberty, which is upside down, what do you see? You see light,” said Martinez, pointing to the reflection of the sunlight and ceiling lights in the upward facing mirror. “You see the light. It’s a reflection of light. It’s a reflection of purity, right, but yet it’s also pornographic, we’re looking up her dress,” he said, speaking of the statue as if it depicted a real human being and not just an iconic symbol. In the process of upending the sculpture, he has turned its meaning upside-down as well: “We’re looking at the bottom, we’re looking at something that was repressed, something that was buried, something that was compressed into the earth, that was never seen. We only see the iconic symbol of what it was supposed to represent.”

The most interesting portion of Martinez’s exhibition, and certainly the most Jewish part, is his hunchback photos. “These are all me,” Martinez explained of the large photos, which depict him in heavy prosthetics and makeup. “I used my own physical body as another form of landscape, because this is like a landscape.”

There is something undeniably topographical about the hunch on Martinez’s back, which he says took hours of special-effects makeup to achieve. But it’s clearly the simple faux tattoos on the figure’s front that make the most provocative statement. Through the prayers from all three Abrahamic faiths, Martinez’s hunchback brings the three traditions together on one deformed body.

“The attempt is not to get into the theological or political or social debate that goes on between these three different groups of people,” Martinez said. “It’s not to suggest that any one of them is right or wrong; it’s actually to try and observe it from a different point of view.

“I mean, do we believe in God?” He asked. “What is our spiritual self? How do we nourish that? How do we exist today?”

Such questions excite Martinez. To him, the idea of in-your-face, statement art, with too didactic a message is a little boring these days. “I don’t know if people respond well to that anymore,” he said.

Martinez wants people who come to see his work simply to be open to possibilities and to find their own interpretations. “I wish that people would come and look and just take a second to think about things that are going on right now, at this very minute, everywhere around them, and somehow reconsider; they don’t have to change their mind.”

But if Martinez seems passive about his work, that’s not so. “I don’t think the work is neutral … and I don’t think it’s passive either … because if it was passive, I’m really not sure why I would do it. And it’s not neutral because neutrality then suggests that I don’t have an opinion, and I think it’s fairly clear there’s an opinion in the room.

“Am I really here only to decorate or do I have another kind of responsibility to speak to the tenets of the time?” Martinez asked. In the context of his work, it is instantly clear that the question was meant to be rhetorical.

Daniel Joseph Martinez’s “I Am a Verb” will be on display through October 20th at Roberts & Tilton Gallery, 5801 Washington Boulevard, Culver City, CA 90232. For more information, visit www.robertsandtilton.com or call (323) 549-0223.