Portrait of David Sassoon, mid-19th century

Attributed to William Melville

Portrait of David Sassoon, mid-19th century

Attributed to William Melville What do many students today learn about the Jewish people? Three lies: we’re “white”; we were all born “privileged”; we’re “colonizers.”

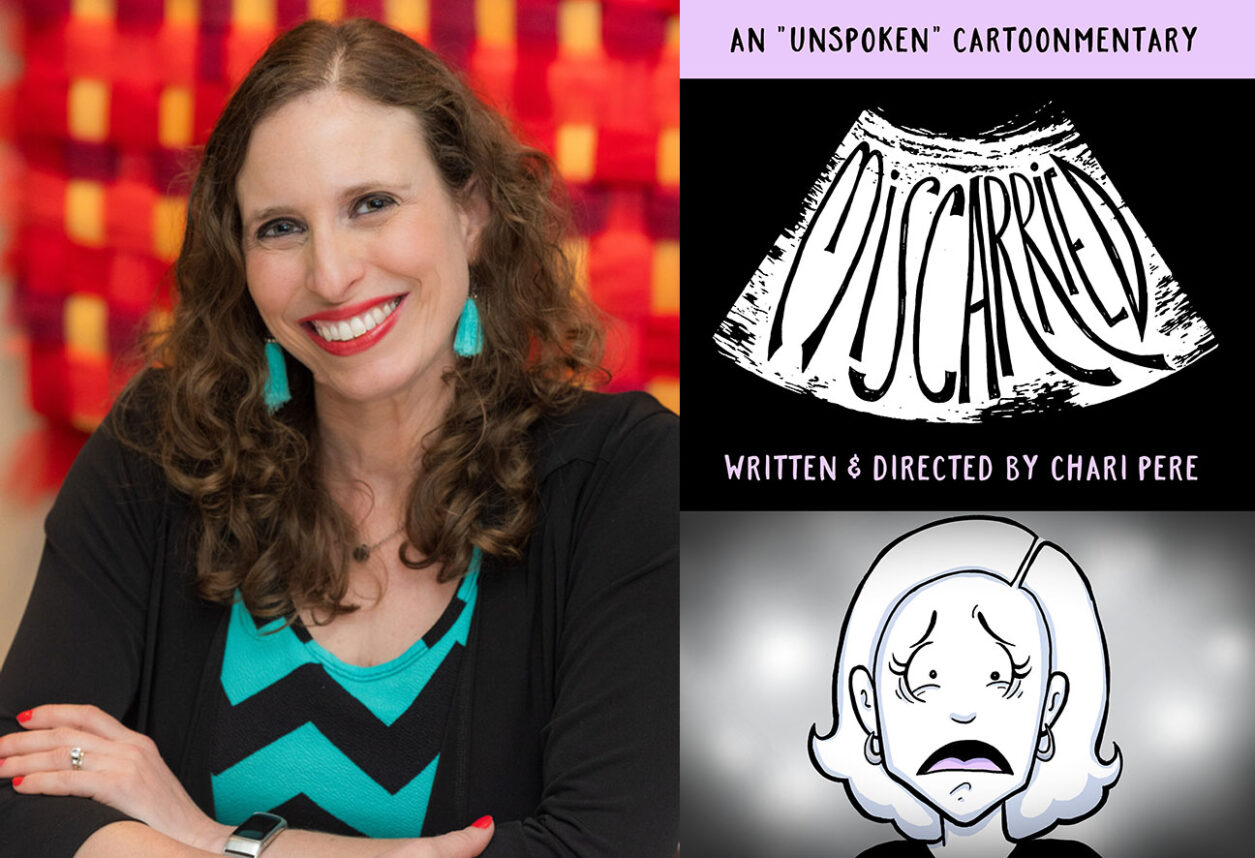

A new exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York City beautifully deconstructs these lies without even trying. “The Sassoons,” on view through August 13, tells the tale of the four-generation Sassoon dynasty through the magnificent art and Judaica they collected after being expelled from Iraq for the sin of being Jewish. The family played a pioneering role in trade, art collecting, architectural patronage, and civic engagement from the early 19th century through World War II.

The dynasty’s patriarch, David Sassoon (1792-1864), had served as treasurer to the Ottoman governors of Iraq and as a leader of the Jewish community in Baghdad, as did his ancestors. But when the Mamluk ruler Dawud Pasha began a ruthless persecution of the city’s Jews in 1830, all Jews were forced to leave with essentially nothing — like every other expulsion story throughout our history — assuming the precarious status of stateless Jews.

Sassoon eventually arrived in the port of Bombay, where he began to trade in spices, fabrics, wheat, and pearls. Deeply observant, Sassoon earmarked a percentage of any profits for tzedakah as well as for maintenance of Jewish sites back in Iraq, beginning the family’s long history of philanthropy. Over time, Baghdadi Jews became one of three well-established Jewish communities in India, together with the Bene Israel and the Jews of Kochi.

Sassoon and his children also began to buy and commission Jewish ceremonial art from Iraq and India, both for their own use and for their community, such as ornate gilt silver Torah finials, which date to the early 1740s and are among the oldest surviving Iraqi Judaica, and an exquisitely illuminated Haggadah, handwritten in Calcutta in both Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic.

Sassoon’s business soon grew to include the opium trade, considered legal by the British at the time, which had escalated after the collapse of the East India Company in the mid-19th century. His business soon extended to China and England, deploying his sons to oversee new branches in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and London.

In the last years of his life, David Sassoon began to lay the foundation of the family’s extraordinary religious and cultural legacy, building synagogues, schools, civic institutions, and hospitals that are still in use today.

Other highlights of the exhibition — more than 120 works collected by the so-called “Rothschilds of the East” — include lavishly decorated Hebrew manuscripts from as early as the 12th century; Chinese art and ivory carvings; rare Jewish ceremonial art; and Western masterpieces including paintings by Thomas Gainsborough and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and magnificent portraits by John Singer Sargent of various Sassoon family members.

Indeed, the next generation moved on to England, where Sir Philip (1888-1939), born to a Sassoon father and a Rothschild mother, became a member of Parliament and hosted royalty at his Mayfair townhouse. Winston Churchill was a frequent guest. To benefit London’s Royal Northern Hospital, Sir Philip mounted 10 art exhibitions in his elegant London home.

The exhibition pays special attention to the Sassoon women, who became discerning collectors, generous philanthropists, and consummate hostesses, and were considered seminal to the family’s integration into British society. Rachel Sassoon Beer (1858-1927) became the first woman in Britain to edit two newspapers, The Sunday Times and The Observer, and played a crucial role reporting on the Dreyfus affair, the infamous antisemitic political scandal in France at the turn of the twentieth century. Her painting collection, sold at auction in 1927, listed, among other great works, one drawing and 15 paintings by Jean Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, John Constable, and Peter Paul Rubens.

Louise Sassoon (1854–1943), like her husband, Arthur, was a personal friend of King Edward VII, whom she often hosted at their home in London and their hunting lodge in Scotland. For her philanthropic work, she was also the first Jewish woman to receive the Order of the British Empire.

David Solomon Sassoon (1880– 1942) collected more than 1,200 Hebrew manuscripts, including some of the oldest extant Hebrew Bibles and illuminated codices (handwritten books). His collection is considered one of the greatest ever assembled. In 1940, during the Nazi bombings of London, he put his precious possessions in storage. “I embraced and kissed them, and I reflected whether I should set my eyes on them again,” wrote the collector. He died without seeing them again, but they survived the war and were later sold; some are now on view at the Jewish Museum.

The last section of the exhibition focuses on the service of a younger generation of Sassoons in World War I. Fourteen grandsons and great-grandsons of David Sassoon fought for the British. Sir Victor Sassoon (1881-1961) served in the Royal Flying Corps, barely surviving an airplane crash that left him permanently disabled. Sir Philip recruited his artist friends, including John Singer Sargent, to cover the war’s devastation; several of these works are on display.

The poetry of Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) became the voice of young Britons traumatized by the unspeakable carnage of trench warfare. Though a brave and much decorated soldier, his graphic portrayal of the trenches and fierce criticism of the establishment were emblematic of a generation scarred by war’s brutality. Some of the journals he wrote and illustrated during battle, including his famous anti-war statement are on view. “A Soldier’s Declaration” was published in The Times of London on July 31, 1917, and read aloud in Parliament.

During World War II, some 18,000 Jewish refugees arrived in Shanghai fleeing Nazi Europe. They were able to survive the war thanks to the money raised by members of the Baghdadi Jewish community who resided in the city at the time. Prominent among them was Sir Victor, who donated considerable funds and placed several buildings at the disposal of the International Committee for European Immigrants.

After being thrown out of Iraq, treated as the “descendants of apes and pigs,” the Sassoon family had the great privilege of working hard to be able to give back — in the arts, through charitable works, and to the global Jewish community. It’s a privilege that those who continue to lie about the Jewish people will never understand.

Karen Lehrman Bloch is editor in chief of White Rose Magazine.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.