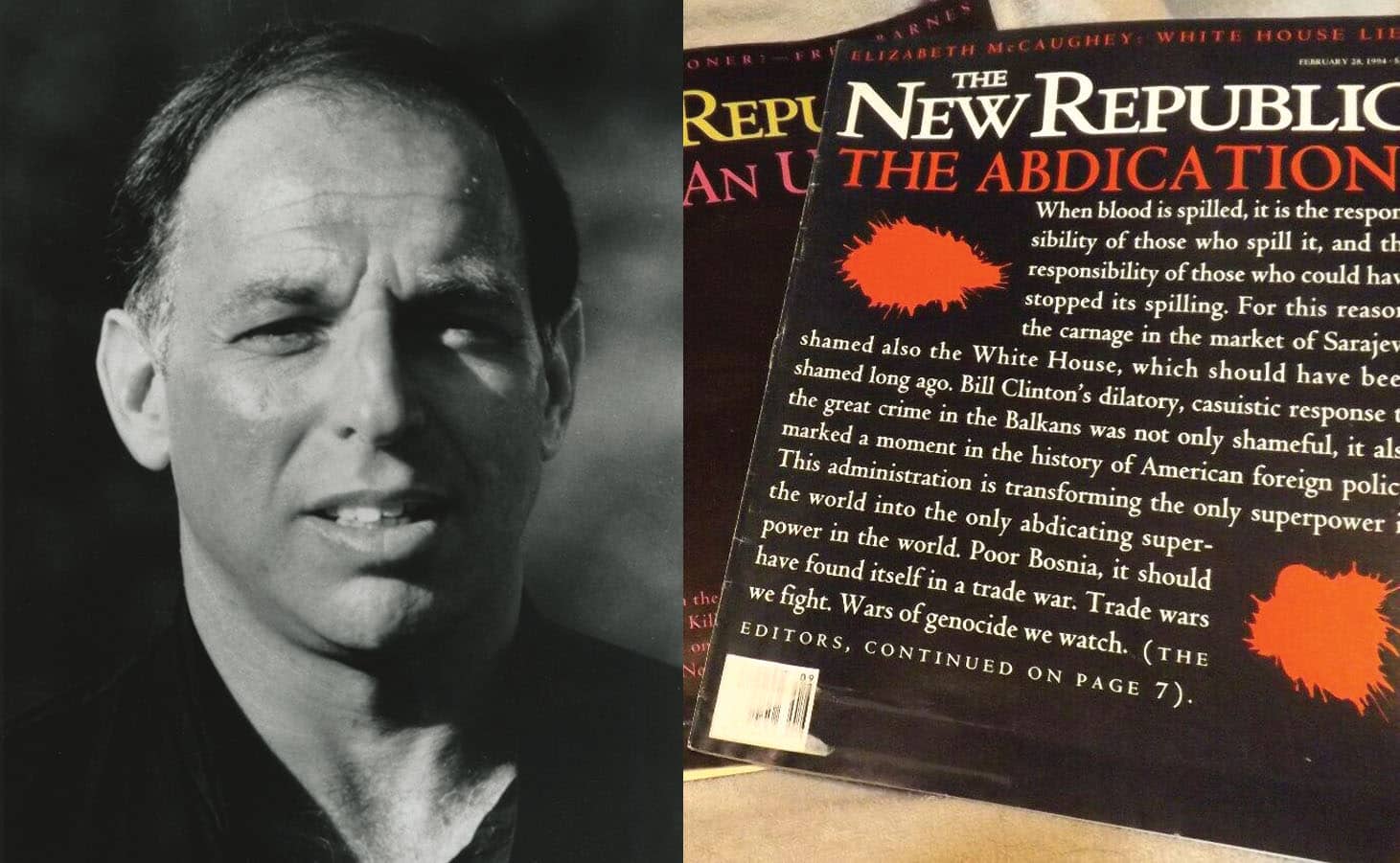

Marty Peret/Credit: Post Hill Press

Marty Peret/Credit: Post Hill Press There was a time when writers cared more about the truth than their status; when reason and respectful debate were privileged over trendy ideology and virtue signaling; when critical thinking and analysis were honored more than branding and “influencers.”

In my 20s, I was lucky enough to work at a magazine that was at the epicenter of truly liberal thought and debate: The New Republic (TNR), in its second iteration. Led by Marty Peretz, Michael Kinsley, Leon Wieseltier, and Rick Hertzberg, TNR was both influential and well-respected precisely because of its complexity — its willingness to call out both sides.

For the nearly 40 years that Peretz owned The New Republic, the weekly magazine was considered essential reading by both the left and the right.

Peretz’s new memoir, “The Controversialist: Arguments with Everyone, Left Right and Center” (Wicked Son), brings us back to a time when intellectual rigor, civil discourse, and vigorous debate prevailed. For the nearly 40 years that Peretz owned TNR (1974-2012), the weekly magazine was considered essential reading by both the left and the right.

The book also offers a chance to revisit a hugely important time in both Jewish and American history. Jewish intellectuals, previously shut out by both universities and established magazines, were finally given a well-respected platform to dissect and devise important ideas. The book also speaks to the current moment of ideological authoritarianism and activist anti-journalism by showing precisely how we got here.

The book also offers a chance to revisit a hugely important time in both Jewish and American history. Jewish intellectuals, previously shut out by both universities and established magazines, were finally given a well-respected platform to dissect and devise important ideas. The book also speaks to the current moment of ideological authoritarianism and activist anti-journalism by showing precisely how we got here.

Early life

Peretz was born on December 6, 1938 to Polish immigrants in a Yiddish-speaking Bronx neighborhood. After Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939, most of his parents’ immediate and extended family were murdered in the Holocaust. “In Germany we were scapegoats; in the Soviet Union some of us, many of us, colluded in our own destruction,” writes Peretz.

Peretz speaks of having a difficult relationship with his father, who nevertheless instilled in him a deep pride in his Judaism. “I was Jewish and American at all times, and there was no contradiction between those inheritances.”

His disdain for over-assimilated Jewry runs throughout the book. He sees Judaism as an ethnicity, which allows for a particularist, as opposed to universalist, sensibility. “My Jewishness… it’s a force in me — not a belief, a force — so strong, so roughly and deeply sensed, that it obviates contradictions with which other people grapple. Jewishness spans 3,000 years, between antiquity, with its rigors and abstractions, and modernity, with its difficulties and contradictions. To me, there are no divides between the eras: Jewishness bridges them.”

Still, he was well aware of the complexities of first-generation Jewish immigration. “[T]he hearts of Jewish immigrants were torn. They loved America but they were somehow still in the old country. Their home had been eradicated forever and there was not even an urge for return. But in her heart, my mother was still there.”

Harvard

After graduating from the Bronx High School of Science, Peretz entered Brandeis University, where he studied with Herbert Marcuse and Max Lerner. Peretz then went on to earn his Ph.D. at Harvard. “The America the Protestants had put in place was opening up. We [Jewish students and faculty] knew it, and it seemed like they knew it too. It was my good fortune to walk up to this golden door just as it was opening up.”

Peretz was one of the founders of Harvard’s Social Studies program, where he became a permanent lecturer and eventually found future TNR writers and editors. He recounts his role in the rise of a Jewish intellectual movement that replaced the WASP establishment: “I was an intellectual entrepreneur.”

He also became deeply involved with the major protests of the 1960s and ‘70s, against the Vietnam War and in support of civil rights. He became close to Martin Luther King Jr. “The civil rights movement was a model for all my activisms to follow because it drew in all kinds, many of them politically minded Jews,” he writes.

In 1968 Peretz tried to forge a synthesis of the civil rights and anti-war movements by organizing the National Conference for New Politics. But at that conference, the Jewish-black Democratic coalition fell apart. One night during the planning sessions, he came downstairs “to find blacks and whites together on my porch singing antisemitic songs about Jewish landlords overcharging and evicting black tenants in Harlem,” Peretz recounts. “I threw them off the porch. … It was true that Jews had more opportunities in America than blacks. But we had struggled too, and now we wanted to break open the Establishment and help other people along.”

It was a defining moment for Peretz, both personally and politically, a harbinger of what was to come: Liberalism degenerating into illiberalism. The alliance between a radical black caucus and white communists soon denounced both Zionism and the U.S. and called for a revolution.

“The antisemitism of the American Left was no different from that of the Communist parties in Eastern Europe, with the new element of race added to the mix,” Peretz writes. It was “the American iteration of the Communist mistake, aided and abetted, again, by Jews rejecting their Jewish identity in the name of an ideology that persecuted Jews.”

In 1967, he married Anne Devereux Labouisse, a Protestant heir to the Singer Sewing Machine Company fortune. “For her, I was an escape. For me, she was an arrival. … I was taking a social leap into the domain of ruling Protestant America.”

Radical chic

From the late ‘60s on, Peretz began to move away from the neo-Marxist Left “instinctually and politically.” Peretz shows the trajectory of how universities became activist anti-universities, beginning in the 1970s. An illiberal ideology “removed from reality” began to prevail, with the dissolution of the center as one of the many negative outcomes.

He began to see much of leftist activism as “theater,” not meant to solve actual problems. “The more radical idealists put justice, feelings, and groups over rigor and individuality.”

This also began his disillusionment with the Democratic Party. “The party I had come up in could no longer govern the society it had helped create. In fact, its governance was worsening America’s problems.” He began to see much of leftist activism as “theater,” not meant to solve actual problems. “The more radical idealists put justice, feelings, and groups over rigor and individuality.”

But Peretz battled the Democratic Party from within, “arguing for the sake of clarifying, holding others to account” and becoming what he calls “a controversialist: Someone determined to stir the pot and who answers to his own emotions and instincts and to not much else.”

“My faith is a very Jewish one, though my life is testimony of many more people than Jews holding it: that the solutions to our problems lie in debate, learnedness, cultivation, and honest differences among smart, talented, committed people.”

The New Republic

Founded in 1914, The New Republic had been the preeminent weekly journal of liberal journalism and opinion in the U.S.

By 1974, TNR was still respected but it had lost its direction and influence. Peretz wanted to restore the magazine to its previous prominence by building a new TNR: Intellectual but not academic, contesting policies from first principles; “protect the private life of individuals from overarching political theories”; argue for why Zionism mattered. He quickly brought on Michael Kinsley, Charles Krauthammer, Rick Hertzberg, and then Leon Wieseltier to create the literary section. “Together we were upstarts — young and pluralist, Jewish and intellectual, not afraid to provoke.”

“We had in our hearts the worst atrocity in recorded history, and it affected our thinking, our approach, to the issues of the day … There had never been such a widely read magazine of Jewish journalists before.”

Understanding what made TNR great under Peretz is really understanding classical liberalism:

• Intellectual honesty;

• Willingness to criticize both sides;

• Unwillingness to conform;

• For nuance, against simple answers to complex questions;

• Importance of discourse, argument, and debate;

• Iconoclastic, unpredictable, provocative;

• Contempt for extremism, dogmatism;

• Gradualism; organic, incremental evolution;

• Intellectual but not academic: a publication of ideas;

• Individuality and freedom, not mandates.

“It was a very Jewish philosophical line to take,” Peretz writes. “Jewish thought throughout the ages was oppositional, discordant, argumentative, and intricate.”

The magazine was for racial equality but wary of racial preference. “The idea of government, the market, or culture defining people by their membership in racial groups seemed exactly like what the civil rights movement had been created to transcend.” He published leading black intellectuals such as Glenn Loury, Albert Murray, and Stanley Crouch.

TNR also tried to stop the Democratic Party from moving away from liberalism. “We thought maintaining a society of multiplicity meant taking a firm line against totalisms … in whatever guise they existed.” The larger effort was to “save [the country] from extremes,” standing firmly against any ideology that provides instant and effortless answers to serious questions.

The magazine’s support for Israel was uncompromising and unapologetic. “Zionism was the one thing I absolutely would not compromise on. … When it came to Israel, I answered to no one but myself.”

As a result, TNR became the center of intellectual disputes about liberalism and America. It remained deeply committed to the classical liberal tradition and willing to defend it against attacks from both sides.

The magazine was not without controversy. One of the most glaring was allowing editor Andrew Sullivan to publish an excerpt from “The Bell Curve,” which argued that cognitive differences between “races” are biological — in our DNA. Despite the protests of all of the editors, his own civil rights background, and the backlash that ensued, Peretz still stands by his decision in the book.

Decency

In 1966, Peretz wrote Ramparts a letter after the leftist magazine “savagely” attacked Max Lerner in a cartoon. “Decency may not be one of the revolutionary virtues but without it we cannot possibly build a good society or … have any notion of what a good society is.”

Indeed, decency is another core element of classical liberalism. But decency did not always prevail in the magazine’s offices in Washington, D.C.

Throughout the book, Peretz discusses his personal issues with anger, stemming from his own anxieties and relationship with his father. He admits to outbursts of anger, and that he “often picked on smaller, weaker people.” As an editor/writer in my 20s, I suppose I fit that category. It wasn’t pleasant. But the positives of working there for three years — most especially working with Leon Wieseltier — well made up for it. Wieseltier championed women writers at a time when we were working 24/7 to prove our intellectual equality. Ironically, Wieseltier was the one who was ludicrously accused of sexual harassment decades later, a “cancellation,” I believe, that was orchestrated by those who were jealous of his brilliance.

One could fault the book for being both self-congratulatory and at times mean. Perhaps the worst example is when he calls editor Michael Kelly, who was killed while covering the war in Iraq, a “nut.”

But as we well know from history, the person and the legacy are often two very different things. And looking back now, I think it’s fair to say that most TNR editors and writers saw the magazine as the most defining, formative part of our careers. I know I do.

Legacy

Peretz heralded a new era of opinion journalism, one that’s needed now more than ever.

“The equal society I hoped for in the ’60s has not materialized; if anything, it has gotten more unequal in the intervening years,” writes Peretz. “Politics are divided, with a media making those divides into cartoons: Between a multicultural statism that doesn’t ring true to the complexity of life on the ground and an antistate conservativism that feels misplaced, grafted onto an era that no longer exists. … The warring parties cannot even refer to a shared reality.”

And the Internet magnified the near extinction of real journalism. “The market … did not value the slow and reasoned thought that was our signature.” Faced with financial pressures from “free news” and the collapse of the liberal center in American politics and intellectual life, in 2012 Peretz sold TNR to Chris Hughes, one of Facebook’s founders, and then in 2016, Win McCormack, a co-founder of Mother Jones, bought the magazine.

In the dozen years since Peretz sold it, the magazine has spiraled into an unintelligible leftist mess that is truly a parody of non-journalism. It’s now the anti-TNR.

Peretz rightfully feels disappointed with the current state of politics and journalism. “Now, we’re in an age of disjuncture, where the wrong people are fighting for the wrong causes. … The migration of radicalism to the national institutions as society at large has lost its mediating institutions.”

The book is a reminder of all that American journalism has lost. It’s an elegy for a world of complex ideas —of reason, truth, and bravery.

There’s no question that if the Peretz TNR still existed today we would not be in the political disarray we’re now in. The book is a reminder of all that American journalism has lost. It’s an elegy for a world of complex ideas — of reason, truth, and bravery.

But he ends the book with faith in the people he’s taught and worked with. And the truth is, most of us who worked there will never be silent about how far journalism — and our national conversation — has fallen, and the dangers of extremism and insipid ideology. We will continue to try to reteach the world the true meaning of liberalism.

The TNR legacy lives on in all of us who were privileged to have played a part in the most important magazine of the 20th century. And for that Peretz should feel that his legacy is quite secure.

Karen Lehrman Bloch is editor in chief of White Rose Magazine.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.