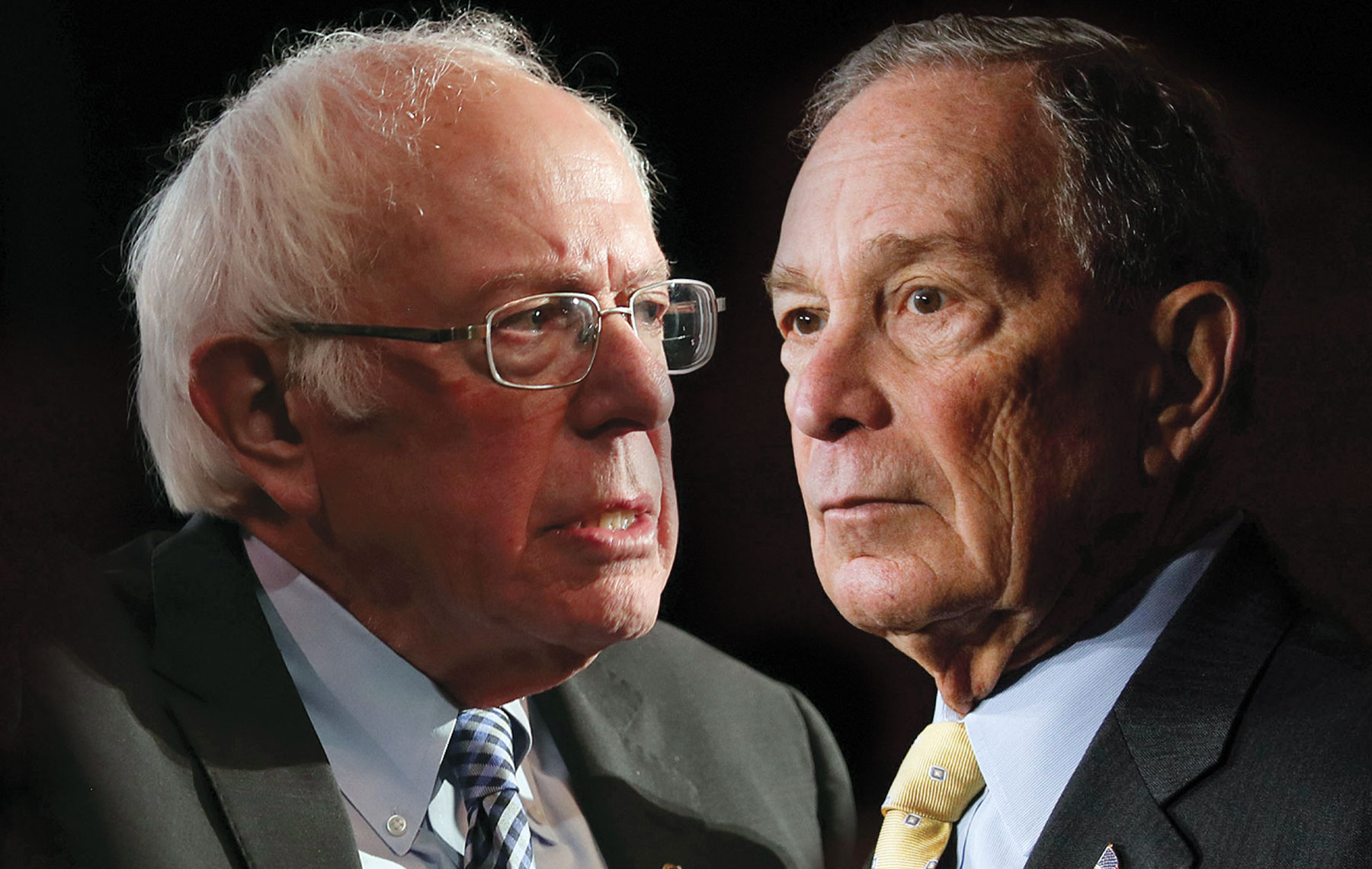

There are two Democratic parties in our country, and it has been clear for some time now that these progressive and centrist factions will collide later this spring in a clash that will define their prospects in this November’s elections and beyond. Until recently, what has been less clear is that the leaders of these two Democratic movements could end up being the first plausible Jewish presidential candidates in our nation’s history.

Bernie Sanders and Michael Bloomberg are not the first American Jews to seek the presidency. However, they already have reached a point of credibility as candidates that no previous Jewish candidate ever has achieved. Sanders has emerged as the de facto frontrunner in the Democratic field. Bloomberg has shot into the top tier of contenders on the strength of unprecedented levels of funding, advertising and field organizing.

While the competition for the centrist lane Bloomberg occupies is fierce, with Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar and Joe Biden still fighting for breathing space, and while Sanders has yet to put away Elizabeth Warren and Tom Steyer in the battle for progressive voters, it is a rational assumption to think the soul and future of the Democratic party will be defined by one of these two Jewish candidates.

Ideologically, the two men have little in common. Sanders is a fierce and unapologetic liberal firebrand; Bloomberg is a careful and measured economic corporatist. Sanders identifies as a Democratic Socialist. Bloomberg previously has registered as an independent and as a Republican. Sanders believes in a dramatically expanded public sector; Bloomberg sees the private sector as the primary engine of economic growth.

Sanders and Bloomberg represent two fundamental aspects of the Jewish psyche, and our choice between them will tell us much more about ourselves than simply our preference on the primary ballot.

They also represent two diametrically different attitudes regarding the United States’ path forward as a nation. Sanders calls for dramatic, sweeping and almost revolutionary change. He has made it clear defeating President Donald Trump is only the first step on the road to a more ambitious set of policy objectives. Bloomberg is a pragmatist who would push hard for big-ticket goals on issues such as climate change and gun control, but within a more traditional approach to coalition-building and public-private partnerships.

But for American Jews just coming to terms with the fact one of our own has the opportunity to become the nation’s first Jewish president, the most profound differences between Bloomberg and Sanders run deeper than matters of public policy or approach to leadership. The two men represent two fundamental aspects of the Jewish psyche, and our choice between them will tell us much more about ourselves than simply our preference on the primary ballot.

Long before beginning preparations for a bar or bat mitzvah, every Jewish child learns two basic truths about our identity as a people. The importance of academic achievement is made clear to us at a very early age. As we get older, we learn in addition to intellectual purpose, our schoolwork is designed to propel us on a path toward professional and economic success.

But we also are taught the importance of helping others, of providing support and comfort for those without the ability to care for themselves. From the earliest examples of tzedakah to more structured volunteer and philanthropic activities, we come to understand an essential part of Judaism is doing our part to repair the world.

In the context of this presidential campaign, Bloomberg and Sanders serve as avatars for these two formative aspects of Jewish culture and identity. Sanders has spent his entire political career aggressively advocating for the rights of the dispossessed and reminding us of the necessity of helping those less fortunate. Although Bloomberg has accomplished a level of economic success far beyond what most parents would dream of for their children, his academic and professional achievements represent a hyperbolic version of the goals set for us when young Jews are encouraged to devote themselves more fully to schoolwork.

Admittedly, both of these examples are oversimplified, as neither man completely limits himself to his assigned box. Sanders consistently advocates for broader academic and professional opportunity, and Bloomberg has been a forceful voice for assistance to those in need. Sanders has achieved considerable personal wealth through investments, real estate and book sales, while Bloomberg has donated billions of dollars toward an array of charitable causes and policy goals. However, while neither of these two sets of goals are mutually exclusive, it is fair to argue both of these men have placed much greater emphasis on one of them. Bloomberg is an example of how we achieve success, even as we share the results of our successes with others. Sanders reminds us of the importance of sharing, sometimes at the expense of our own potential achievements.

Bloomberg is a pragmatist who would push hard for big-ticket goals on issues such as climate change and gun control, but within a more traditional approach to coalition-building and public-private partnerships.

As Jews, we can and should strive for both sets of objectives. We want to provide for our families and help others in need. Sanders and Bloomberg are not forcing us into a choice between the two, but rather reminding us of the importance of each. Both men want to help repair the world, but through dramatically different courses of action — and so our choice between their candidacies tells us which of those two approaches is more in concert with our own worldview.

Judaism isn’t about choosing success or sharing to the exclusion of the other, but about how we integrate and balance the two. The domestic policy goals Bloomberg and Sanders prioritize are unusually high-profile reminders about two ways to achieve that balance.

Similarly, their differences on Israel and Middle Eastern policy are telling. Not surprisingly, both candidates look at Israel’s economy through a similar prism as the way they view questions about job creation and economic growth in this country. Both approach these matters based on what they’ve learned from their personal and professional experiences. Sanders is the former kibbutznik who believes in the collectivist and communitarian version of the Israeli ideal. Bloomberg is the technologist who personifies the “Start-Up Nation” ethos that has propelled the Jewish homeland to great economic heights. Israel benefits from both attitudes among its own citizens; Bloomberg and Sanders reflect those differing visions in that country, too.

Bernie Sanders and Michael Bloomberg are not the first American Jews to seek the presidency. However, they already have reached a point of credibility as candidates that no previous Jewish candidate ever has achieved.

Just as stark are their differences on geopolitical matters. Sanders is part of a rapidly growing faction of Democratic progressives who aggressively question Israel’s strategy for co-existing with the Palestinians and place much greater emphasis on the Palestinian perspective than most Israeli political leaders. Bloomberg approaches these questions in a more traditional manner, emphasizing Israel’s safety and security needs and the threat Palestinian violence poses. Sanders would condition the U.S. aid to Israel on significant changes in Israeli policy toward the Palestinians; Bloomberg rejects such a negotiating strategy out of hand.

Again, the two Jewish candidates stand for different mindsets toward Israel among American Jews. Our community agrees on the need for peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians, but there is growing discord about how to get there. Bloomberg and Sanders speak effectively for the two main schools of thought on these matters among American Jews. This means if the two of them end up as the finalists for the Democratic nomination, many of us will be forced to take sides in this debate much more unambiguously — and much less comfortably — than we have in quite some time. It’s one thing to register approval or disapproval toward Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu from thousands of miles away; casting a ballot in a U.S. presidential primary for one form of Zionism or another is a much starker choice to confront. But Sanders and Bloomberg encapsulate two dramatically different ideas of not only what we want our country to be, but what we want Israel to be.

Finally, Sanders and Bloomberg represent versions of how we see ourselves as part of American society. We are outsiders here, as we have been in every country in which we have lived outside of our homeland. But one of the most difficult questions with which we struggle is what kind of outsiders we are; again, Bloomberg and Sanders represent very distinctive answers to that question.

What sort of outsiders are we? Truth be told, we still often see ourselves as an oppressed minority. The alarming increase in violence against our synagogues and our people have intensified this feeling, but it is a self-characterization we have justifiably carried with us for thousands of years. However, American Jews have achieved remarkable academic, professional, economic and political success, which means other minority communities regard us in a much different light than how we see ourselves.

One of the greatest challenges faced by American Jews in recent years has been the weakening of our relationships with other minority communities. There is a long and honored history of Jewish involvement and leadership in a range of civil rights and social justice efforts through the years. Yet public opinion polls suggest increasing numbers of minority voters no longer regard either the Jewish community here or the State of Israel as a positive presence. Finding a way to repair those relationships is an urgent necessity.

The recent fight in Sacramento over California’s ethnic studies curriculum for high school students crystalizes this disparity in a frustrating but helpful way. The courses have focused on four specific minority communities: African Americans, Latinos, Asian Pacific Islanders and Native Americans, and have included disparaging references to Jews and Israel. Through the commendable work of the Jewish Legislative Caucus, the insults will be removed from the curriculum. But it is very clear California’s state government has no intention of expanding the definition of “ethnic studies” to include those of Jewish ethnicity (as well as several other ethnic groups). We believe our story should be discussed alongside those of these other minority groups; the state of California emphatically disagrees, citing the commonly used definition of “ethnic studies” in higher education to include only the previously named four groups.

In the context of this presidential campaign, Bloomberg and Sanders serve as avatars for these two formative aspects of Jewish culture and identity.

The dichotomy is obvious: We American Jews see ourselves as an ethnic group, with the outsider status that term suggests. Political and educational orthodoxy says we are not, that our successes in this country mean that term no longer applies. This brings us back to what Sanders and Bloomberg represent in us.

Sanders is the ultimate political outsider, a status in which he has reveled throughout his career. He is never happier than when he is raging against the machine and marshalling the resources and energies of fellow outsiders to storm the gates of power. On the other hand, Bloomberg’s professional and political achievements have brought him inside those gates and led him to the conclusion that working for change within the system is more effective than agitating from without. The part of our self-regard as Jews that reminds us that we are outsiders identifies with Sanders; the part that reflects our successes helps us understand Bloomberg. As a people, we are both insiders and outsiders in U.S. society. Bloomberg and Sanders each represent one aspect of that whole.

If one of these two men does become president, it would seem the American Jewish community would have achieved the ultimate in insider status. But African Americans have learned since Barack Obama’s election 12 years ago that even achieving the highest office in the land does not eliminate long-standing hatred and anger. A Bloomberg presidency would reinforce the perception of Jewish Americans as insiders to a much greater degree — much as John Kennedy’s election symbolized a similar achievement for Irish Catholics — while Sanders would presumably use the office’s bully pulpit as a platform in a way that would underscore our history as those excluded from the halls of power.

The two Jewish candidates stand for different mindsets toward Israel among American Jews. Our community agrees on the need for peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians, but there is growing discord about how to get there.

The animosity directed toward Jews comes from both the far right and the far left. Sanders and Bloomberg are much more comfortable calling out the ultra-conservatives whose exclusionary nationalism habitually oozes into anti-Semitism than those on the far-left fringes, whose anti-Zionism frequently bleeds into anti-Semitism as well. There is little doubt both men would forcefully denounce the haters on the right. The more challenging question is how would either, as the first Jewish president, confront those voices coming from the left.

By definition, progressives are committed to fighting on behalf of the underdog. This discussion becomes more complicated when it comes time to determine who should qualify for underdog status. American Jews still regard themselves not just as outsiders but as those who face persecution because of their beliefs. We see ourselves as David, but much of the rest of society thinks we are Goliath — and committed progressives rarely are willing to wield their slings on behalf of a giant.

On this front as well, the differences between what Sanders and Bloomberg would represent are profound. Does the Sanders brother-in-arms approach yield more likelihood for success than Bloomberg’s philanthropic mindset? Is it better to say “We’re David, too” in the face of understandable skepticism, or to admit we once were David and want to help other challenged communities rise the way we have?

Judaism isn’t about choosing success or sharing to the exclusion of the other, but about how we integrate and balance the two. The domestic policy goals Bloomberg and Sanders prioritize are unusually high-profile reminders about two ways to achieve that balance.

This is a challenge we face in our own lives when interacting with other communities. Bloomberg and Sanders offer two contrasting approaches for us to consider and potentially follow. Our history suggests we are coalition builders; our contemporary approach leans more toward philanthropy than interpersonal involvement. Both are necessary parts of the solution, but Sanders and Bloomberg would achieve this balance in different ways.

The primary season is far from over, and it is possible to see the nomination fight continuing into the summer. Sanders seems to be solidifying his hold on the party’s progressive bloc, but Bloomberg’s path though the center lane will be much more complicated. For most Jewish voters — who oppose Trump’s re-election by immense margins — the decision will come down to which candidate is better positioned to defeat the current president in a general election matchup.

Even here, Bloomberg and Sanders offer contrasting formulas to victory, as Bloomberg and other centrists argue they are better positioned to persuade undecided voters, while Sanders and his fellow progressives make the case that motivating the Democratic base to turn out in high numbers is the more effective strategy. (Trump will do his best to leverage his support for Israel to poach even a small percentage of Jewish voters, which could play a decisive role in key swing states such as Florida and Nevada.)

Sanders is the ultimate political outsider, a status in which he has reveled throughout his career. He is never happier than when he is raging against the machine and marshalling the resources and energies of fellow outsiders to storm the gates of power. On the other hand, Bloomberg’s professional and political achievements have brought him inside those gates and led him to the conclusion that working for change within the system is more effective than agitating from without.

If Bloomberg and Sanders emerge as the leaders of the two wings of the Democratic Party, the stark contrasts between them on economic policy will be instructive but fairly typical. The dynamic between the two on the Middle East is less familiar to us but appears to represent the emerging future on Israel-related issues in the years ahead.

But in addition to their vast differences on matters of public policy, a Sanders-Bloomberg showdown also represents an unusual opportunity for we American Jews to look within ourselves to consider questions of who we are and who we want to be. Bloomberg and Sanders represent aspects of our core Jewish identity and seem poised to force us to decide which parts of ourselves are the most important to each of us.

Dan Schnur is a professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies and Pepperdine University.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.