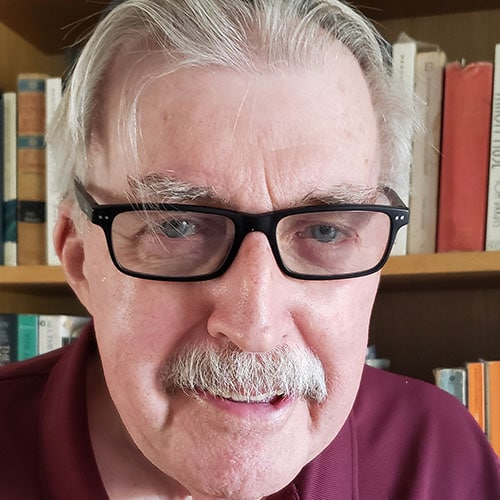

Deborah Schmidt

Deborah Schmidt Having only become executive director of the Sandra Caplan Community Beit Din in January, Deborah Schmidt cannot say whether there is a typical convert to Judaism.

Instead, the former attorney alludes to a Midrash that holds “we all stood at Sinai, all Jewish souls. Some Jewish souls might have gotten lost along the way.

Over time and circumstances, we can bring them back to the Jewish people.”

Schmidt’s job is not to bring back those who may have strayed but to oversee conversion candidates’ official final steps.

As her predecessor Muriel Dance explained, “The Beit Din is not about teaching a candidate one more thing. It is an opportunity to find out what called these people to our tradition.”

An irony — or coincidence — of Schmidt’s leadership is that she need look no further than a family photo for so-called typical conversion case.

Take her sister-in-law, who is Japanese. She met Schmidt’s brother in Bali when he was on holiday. He lived in Mitzpe Ramon, two hours south of Be’er Sheva.

“She made her way there and became part of the Jewish people in Israel,” Schmidt said proudly.

“You might ask, ‘How does a woman from Japan find a home within Judaism?’”

The born Jew marveled at the sight of a new Jew, her relative. Schmidt happened to be in Israel at the time. “I witnessed her immersion in the mikveh,” she said. “For her, it was absolutely transformative. She finally had found her home.”

The erstwhile attorney believes “every single step along my journey has prepared me.”

Schmidt’s new position is not the fulfillment of a longtime dream. But the skills she brings to leadership of the Sandra Caplan Community Beit Din — administration, organization, pastoral, bringing people together – were deemed ideal for Dance’s successor.

The Beit Din is the only pluralistic standing rabbinic court for conversion in the world. It was named for the late wife of the founding donor, George Caplan, who wanted to ensure “there is a place to embrace seekers of Judaism,” Rabbi Jerrold Goldstein, one of the Beit Din’s founders, in 2002. Since then, the Beit Din has welcomed more than 800 new Jews.

From her professional experience, Schmidt, a mother of four daughters, understands a prospective convert’s curiosity and apprehension at entering a new form of life.

For complex reasons, there came time for a career change. “I had been doing law for a long time,” she said, “and then in 2008 there was the financial meltdown. I also had personal issues in my family that prompted me to think about doing something more human-faced. And I did it.”

What new responsibility has the new leader been anticipating most? Without hesitation, “meeting candidates and hearing their stories. The other part of starting this position is my chaplaincy work.”

Schmidt returned to the classroom in 2011 and graduated from the Academy of Jewish Religion, California, in 2014 with a chaplaincy degree. In the decade since, she has served as chaplain at Cedars-Sinai, Beit T’Shuvah treatment center, at jails and in hospice.

She chose chaplaincy as a new career because she was seeking “something that was more people-facing but wasn’t law. It was really hard. Every organization I spoke to said, ‘You can do our legal work.’ I’m, like, ‘No, I don’t want that.’”

Schmidt’s route from law to chaplaincy to the Beit Din seems to have been relatively smooth.

She explained that Muriel Dance has been a mentor for years. “In chaplaincy school, I did clinical pastoral education unit at Skirball Hospice where she was my supervisor. I got to know her, and we have had a relationship since 2012.”

Periodically, they checked in on each other. Last year when Dance was preparing to retire, she let Schmidt know.

“She thought I would be a good fit,” said the new executive director. “When she announced her retirement, I applied and went through the process.”

Schmidt said it wasn’t that all career roads led to the Beit Din. “But I believe my accumulation of skills and knowledge have culminated in this,” she said with a smile.

Without hesitation, she described the most appealing portion of this latest new scenario in her professional life.

“Meeting the candidates, listening to their stories, holding space for them in the holy journey they are taking,” Schmidt said.

Having been trained in numerous professional avenues, she confidently reaches a conclusion that she is ideally suited for her newest calling.

“I am really a listener.” – Deborah Schmidt

“I am really a listener,” she said. “Chaplaincy essentially is being present, holding space, listening to someone’s story because it is theirs to tell, theirs to live and for me to hold space.”

Through no coincidence, she identifies these as the same skills she brought to chaplaincy, to being with sick people at the end of lives.

Throughout her legal career, Schmidt had both hands on the wheel. Here, she is to sit back and listen. Does that suggest she is loosening her grip?

She won’t be taking he hands off the steering wheel because there is another dimension to her duties.

“Part of my role is to make sure we have the dayanim (rabbaim) for the Beit Din, that we are organized and have everyone’s conversion records,” said Schmidt.

Once she was offered her new position, a change washed over her. She noticed what she calls New Jews everywhere, those who may look different from Jews she and other lifelong Jews grew up with. “Our community is so much richer because of their participation,” she said. She maintains the community piece enables people to inquire about Judaism without being scared of being overwhelmed.

Schmidt and many others grew up being taught “traditionally you are supposed to turn the convert away.”

But remember, she said, “we have stories in the Talmud of many, many people who were New Jews.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.