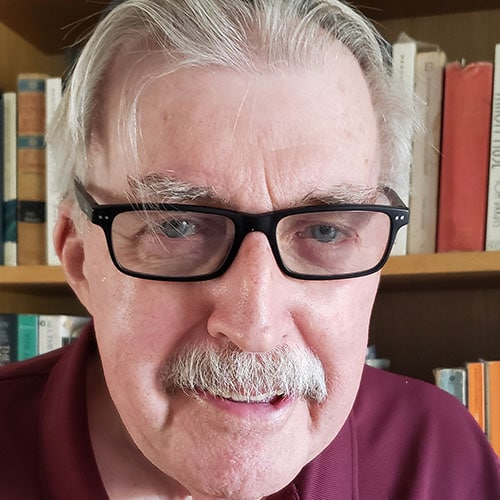

From left, Rabbi Jerrold Goldstein, his wife Frances and Muriel Dance

From left, Rabbi Jerrold Goldstein, his wife Frances and Muriel Dance

On May 29, the Sandra Caplan Community Beit Din will honor one of its founding rabbis and salute its 20th anniversary. Friends and some of the Beit Din’s 726 converts will gather at Leo Baeck Temple in tribute to Rabbi Jerrold Goldstein, one of the founders. He was the details maven.

The Beit Din is the only pluralistic standing rabbinic court for conversion in the world. It calls Shavuot “the holiday of choosing Judaism,” the day God gave the Torah to Moses.

Friends and some of the Beit Din’s 726 converts will gather at Leo Baeck Temple on Sunday afternoon in tribute to Rabbi Jerrold Goldstein, one of the founders. He was the details maven.

“We All Choose Judaism” is a Beit Din motto. The 128 rabbis in the system are from five streams of Judaism – Reform, Conservative, Reconstructionist, Transcendental and Renewal.

“Rabbi Jerrold is the one who knew how to put everything into practice,” said Muriel Dance, the Beit Din’s executive director. “Some are good at having ideas, but putting them into practice is more complicated.”

Dance called Goldstein a “builder” who brought innovative ideas to life. Working with fellow founders Rabbi Elliot Dorff and the late Rabbi Richard Levy, Goldstein wrote most of the group’s early documents, especially regarding standards, the operating principles and their application.

Goldstein is credited with shepherding the candidates and their sponsoring rabbis through the process. Dance said Goldstein, a 60-year veteran of the rabbinate, set up a way to convene three rabbis to sit on the Beit Din and developed a method for listening to candidates tell their stories.

A native Angeleno, Goldstein had a ready reply when asked about his main contribution. “I was a good note-taker,” he said before explaining his meaning.

In 1997, he and five other rabbis started meeting monthly to talk about a dream they had for conversion and structure on an unusually large-scale basis. “Out of those discussions the concept and then the principles emerged,” he said, for what became this Beit Din.

Pluralism was their goal. “We all agreed that conversion ought not to be denominational or a single synagogue,” said Goldstein. “We are welcoming persons into the Jewish people. There are many paths in Judaism, historically and in contemporary life.”

Goldstein said his Hillel campus experiences – most recently at Cal State Northridge — led him to a commitment to pluralism.

“My job was to help young Jews find their path in Judaism, and then express it,” he said. “I was helping Orthodox Jews to be Orthodox. I was helping Reform Jews to be Reform. I was helping unaffiliated Jews – the majority – appreciate what it meant to be an engaged Jew and to include some kind of religious dimension in their lives.”

“I was helping Orthodox Jews to be Orthodox. I was helping Reform Jews to be Reform. I was helping unaffiliated Jews – the majority – appreciate what it meant to be an engaged Jew.“ – Jerrold Goldstein

The 86-year-old Goldstein is proud he had the advantage of being raised in the open Jewish community that is Los Angeles.

“This is a place where Jews find acceptance,” he said. “Nobody asks, ‘what denomination do you belong to?’”

The Beit Din was named for the late wife of the founding donor, George Caplan, who wanted to ensure “there is a place to embrace seekers of Judaism,” he said. ”[That] is a passion that gives meaning to my life and her memory.”

Dance said the Beit Din “is not about teaching a candidate one more thing. It is an opportunity to find out what called these people to our tradition. Of course, one question is, do they know enough to do Jewish? Another is, are their motivations authentic?”

A former university dean on numerous campuses, Dance is a close observer of the conversion candidates.

“We want to affirm them where they are,” she said. “We never ask a trick question. Our questions are open-ended. We want to find out what they know and how they have internalized what they have been studying.”

The Beit Din requires an Introduction to Judaism course or its equivalent before a candidate stands for conversion. “Some might say we are traditional in our standards,” said Dance. “Coming before a rabbinical court, men must have brit milah or a circumcision that has been affirmed, and mikvah immersion.”

Dance identified three kinds of candidates, along with children. There is a prospective spouse or partner of a Jewish person, “seekers, people who are soul-yearning for something that gives meaning, who understand there is something larger beyond human life” and people who find out they have Jewish heritage through DNA testing.

Dance became familiar with the third group through Birthright because “they are very liberal in their interpretation of people they welcome on Birthright trips. “A young woman goes on Birthright because she has a Jewish parent, although she was raised by her Chinese mother. After Birthright she says she wants to reclaim her father’s Judaism now that she knows more about Judaism. So the mother and daughter studied together for more than a year, and then both came to the conversion mikvah.”

The pandemic did not interrupt the flow of conversion candidates. In the first year there were 46 and last year, there was a record 63 conversions.

While many candidates are coming because their attraction to Judaism has been affirmed by DNA tests, said Dance, DNA is much better at detecting Ashkenazim than Sephardic or Mizrahi Jews. Almost a quarter of conversion candidates are Jews of color.

The Beit Din has created a conversion mentor program to guide and guard new Jews down the highway of a different lifestyle after the ceremony is over.

“Not everyone needs a mentor,” said Dance. “But a significant number of single people convert, and they do not have a built-in family for support.”

Dance grew up in Los Angeles but her career took her away for decades. When she returned, she explored four synagogues before settling at IKAR.

“I began inviting people to sit with me at my congregation,” she said, “because it’s hard being a newbie.” ■

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.