We often have tunnel vision when we’re in a difficult place. “I just need to get through this,” we say. And it’s true — whether it’s biblical Egypt or a rough patch in our own lives, sometimes we need to focus our resources and attention on getting ourselves safely to the other side.

But once we get through, where are we?

Occasionally, we jump straight into a new chapter of life feeling fully resolved and at peace. But more often, when we exit crisis, we land squarely in transition. We find ourselves wandering in the wilderness, just like the Israelites after their exodus from Egypt.

My college professors in the ’90s were fond of the phrase “liminal space” — that threshold betwixt and between, neither this nor that. This term was so common that I began to suspect this love of liminality was an academic trend. Perhaps border spaces had been disregarded for years and only now were being rescued from obscurity?

But, of course, my postmodernist professors were not the first to pay attention to liminality. In fact, the fourth book of the Torah takes place almost entirely in liminal space. In English, the book is titled Numbers, but in Hebrew, the book is called Bamidbar, literally, “in the wilderness.”

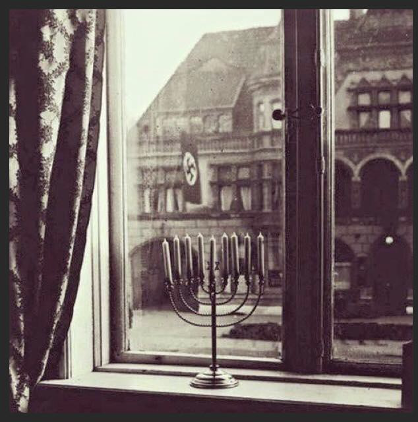

I’ve long been captivated by this image of rotting manna. What can it teach us in our own times in the wilderness?

In Bamidbar, an entire generation finds itself newly freed from oppression, but also newly uncertain about its day-to-day life, not to mention its future. No longer fearing for their lives, the Israelites begin to discover things about themselves that could not emerge while they were still struggling just to survive.

For example, the Israelites discover that when faced with physical discomfort and uncertainty, their mood quickly can turn from joy to petulance. They also begin to feel out the heights and depths of their spiritual lives — from a new relationship with the Divine, who leads them in a pillar of cloud by day and of fire by night, to experimenting with idolatry in the Golden Calf episode.

Some of these lessons must have felt good in the moment; others were likely excruciating. All of them were crucial in the formation of a tribe.

In the same way, when we find ourselves in a liminal space after a crisis, we encounter parts of ourselves that surprise us. After a move; or in early parenthood; after initiating a necessary breakup; or having recovered from the initial stages after a loss — at these times we learn things about ourselves that can be discovered only in the wilderness.

During this time, we also are open to profound spiritual lessons because we’re liberated from our routines and with them, our complacency. The manna that fell from heaven during the Israelites’ journey is a perfect example of this. It is as if God is saying, yes, you need to eat, and I will help you with that, but you also need to learn to be less anxious, and I will help you with that, too.

And so, according to tradition, the manna appeared each morning like dew, it tasted like each person’s favorite food, and — my favorite part — if they gathered more than one day’s supply, it simply would rot. (Except for Fridays, when they could gather two days’ worth to avoid working on the Sabbath.)

I’ve long been captivated by this image of rotting manna. What can it teach us in our own times in the wilderness?

To me, the deepest teaching of the manna is a teaching about time.

We must be present in the moment, for time cannot be saved or stored. It can be experienced only as we live it, as it runs through our fingers.

When this mysterious, magical food appeared one morning, the Israelites asked, “Man hu?” (“What is this?”) This is where the name “manna” comes from — it essentially means, “What?”

The spirit of “what,” of open-minded inquiry, is the spirit of the wilderness. In walking out of our bondage, we also leave our preconceived notions about ourselves and the world. We are like children, looking around us, asking, “What is this?”

Perhaps that question itself is the secret heart of our being. Perhaps it is all we truly have.

Alicia Jo Rabins is a writer, musician and Torah teacher who lives in Portland, Ore.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.